Deciphering an Ancient Medical Text With the Help of X-Rays

It was hidden under an 11th-century manuscript full of hymns.

Some ancient texts are lost to the ages. Others are hiding in plain sight, and technology can bring them back to life on the page.

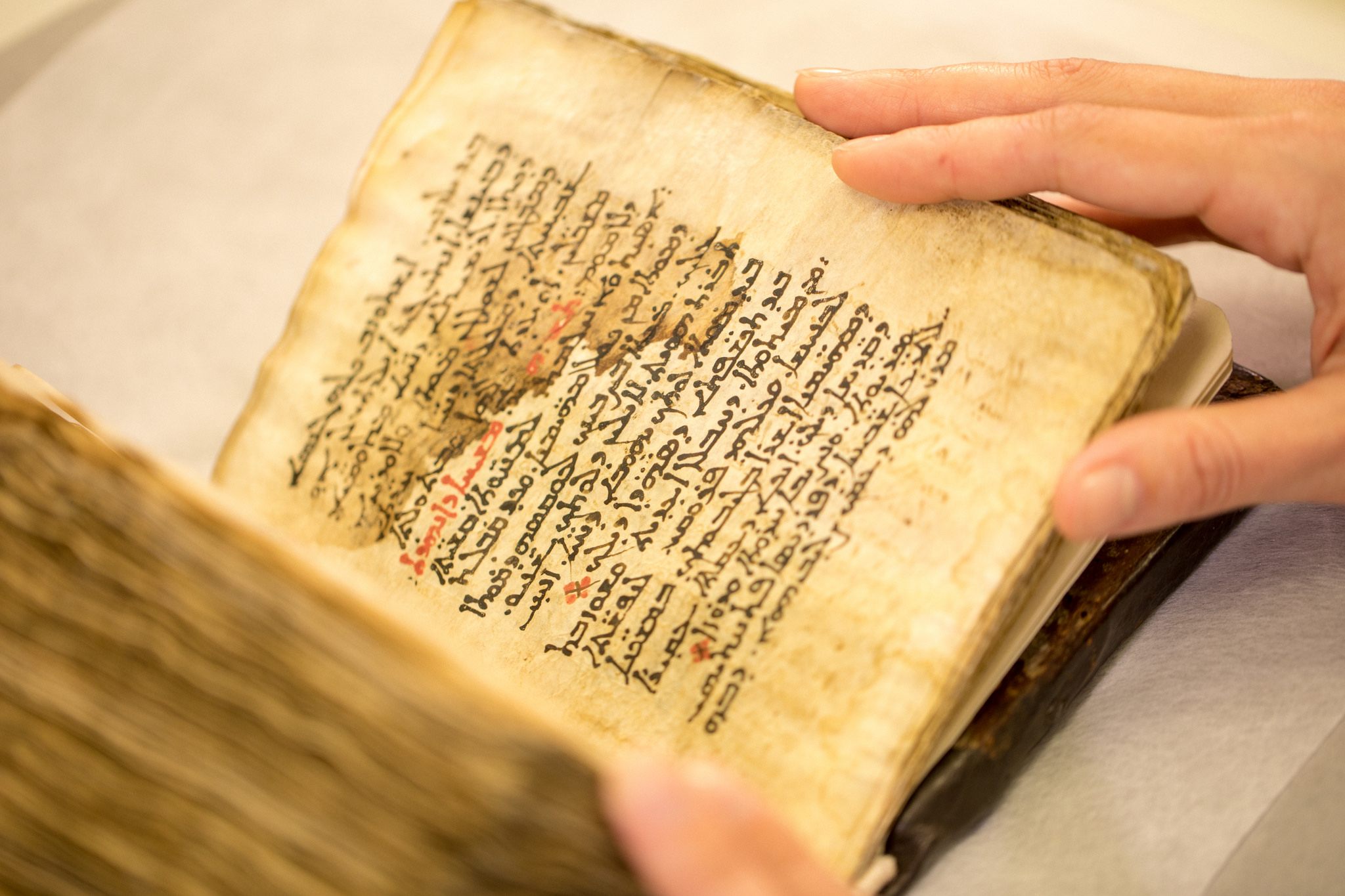

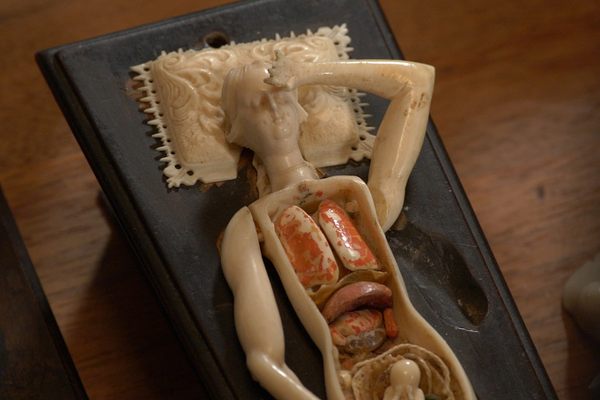

Take the so-called Galen Palimpsest. The parchment leaves of the leather-bound manuscript carry hymns dating to the 11th century. Beneath these inscriptions, though, is an earlier medical treatise—a 6th-century Syriac translation of a text by Galen of Pergamon, a physician and anatomist who attended to Roman emperors. “Little of Galen’s advice would stand up to modern scrutiny,” the New York Times noted in 2015. (The article also quoted a scholar who summed up Galen’s philosophy, which included theories about balancing the body’s humors, as “completely bonkers.”) No matter: Researchers still want to glean as much as possible from his writings, which were foundational strata in the bedrock of Western medicine.

Historically, parchment was a pricey commodity, and it was common practice for a scribe to scuff away earlier text and then lay down fresh lettering. But that doesn’t mean the bottom-most layer is gone forever.

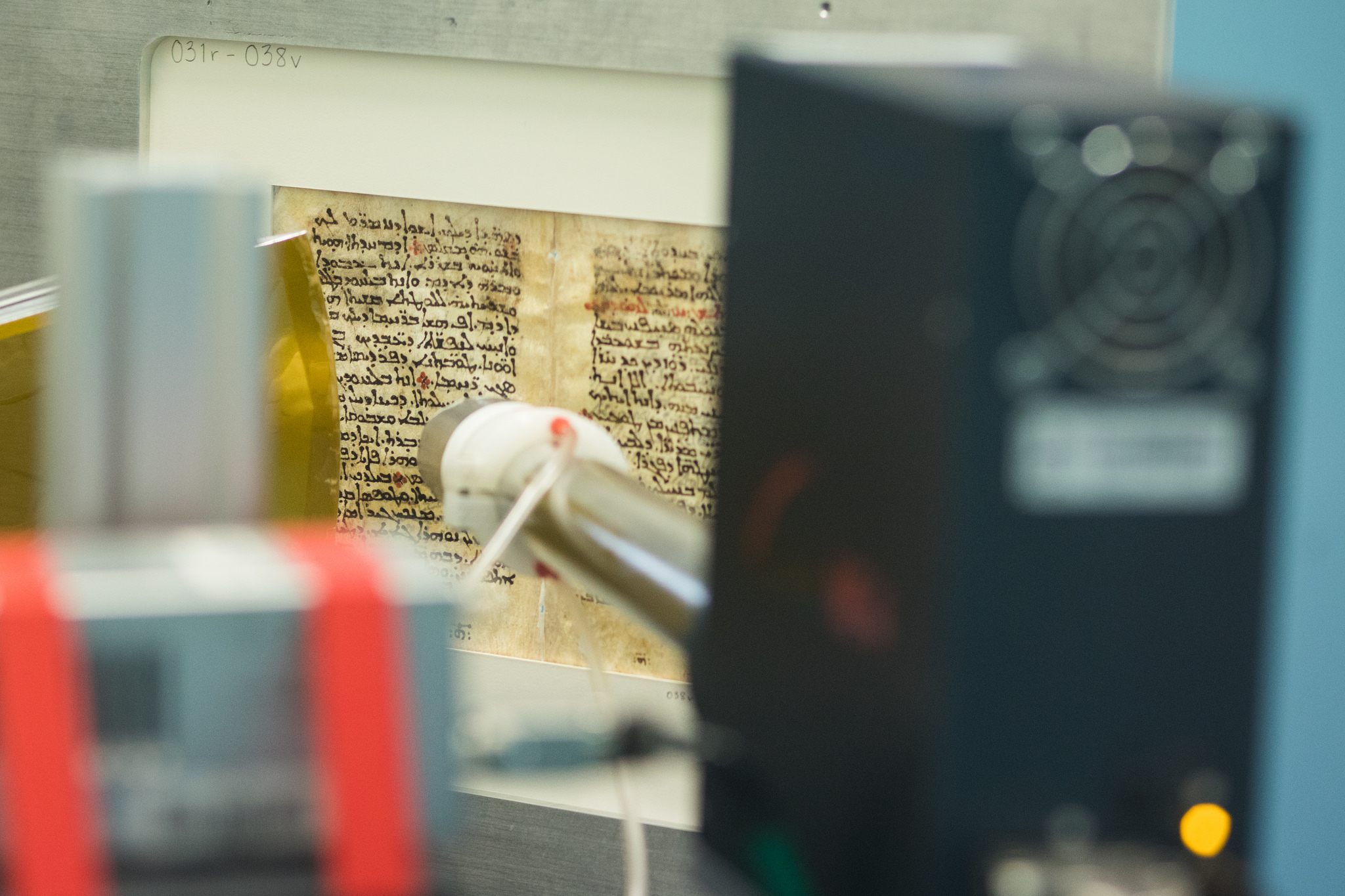

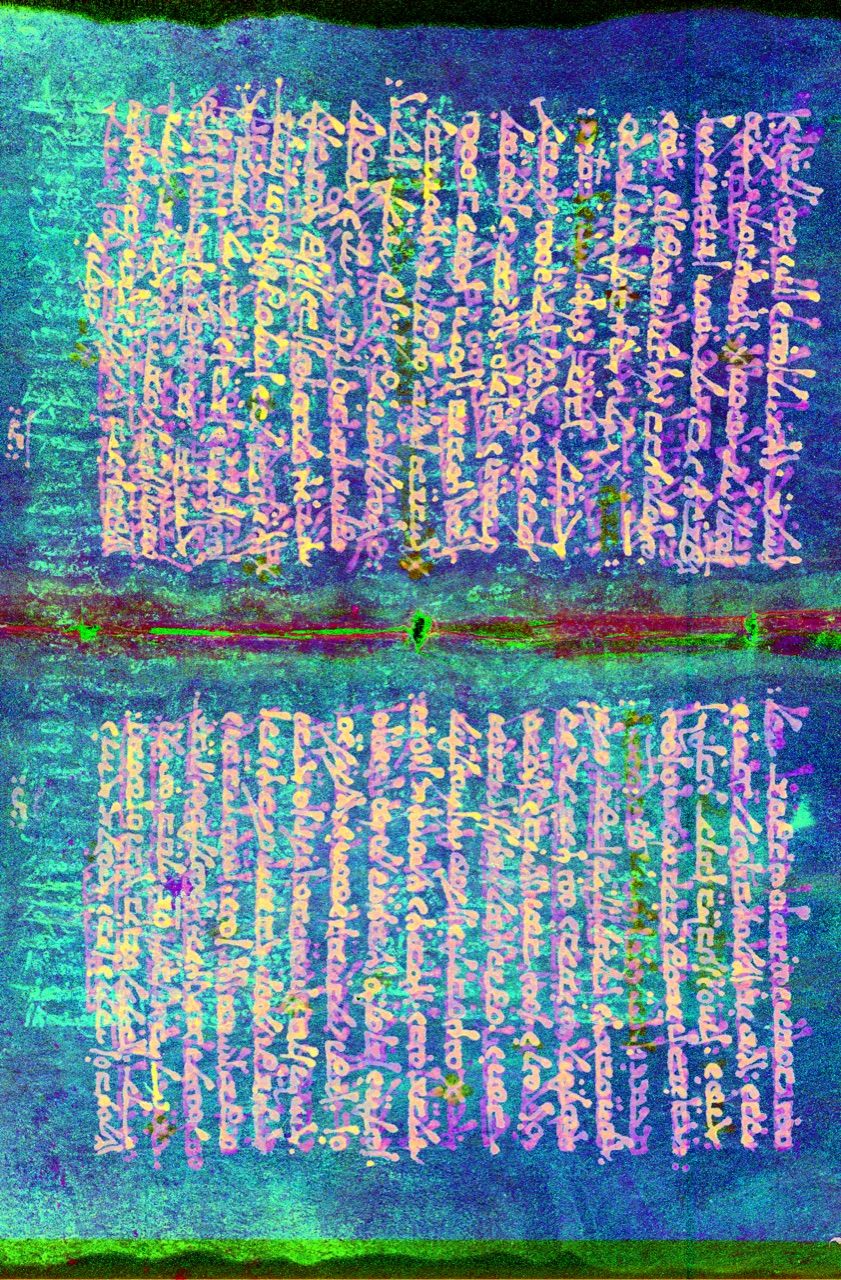

Earlier this month, an instrument at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory blasted the manuscript with X-rays to get a closer look at the traces of the text that have been buried for millennia.

This technology lets researchers get a closer look at the layered text without threatening the integrity of the pages. By penetrating the document with X-rays—instead of trying to lift the newer writing from the surface—“you don’t have to jeopardize one part of the document to learn about the other,” said Kristen St. John, head of conservation services at Stanford University Libraries, in a news release.

When it comes to distinguishing the old from the even-older inscription beneath it, the researchers caught a serendipitous break: The buried Syriac text is organized horizontally, while the 11th-century characters run vertically.

It takes roughly 10 hours to scan a page, and the team is working on 26 in all. Each scan contains more data than a human could wrangle. To help sift through it all, the team is working with machine-learning tools. The images will eventually be added to a digital trove manned by the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries.

Already, the scans have delivered new insights. A page that had long been undecipherable, unyielding to prior attempts to crack it with other forms of imaging, proved to be a portion of a preface. “The first initial results are incredibly mind-blowing,” the University of Manchester classicist Peter Pormann told Newsweek. As work marches along, researchers hope the text will yield much more information to diagnose.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook