The Modern Resurrection of the Dybbuk, Demon of Jewish Folklore

How a superstition goes from the Talmud to TikTok.

In 2003, a wine cabinet in Portland, Oregon, somehow made headlines. The owner of the foot-and-a-half-tall wooden bit of decor, Kevin Mannis, had listed it on eBay alongside an elaborate story. He claimed that the cabinet had previously been owned by a Polish Holocaust survivor and was inhabited by a powerful demon known as a Dybbuk. Since it came into his possession, he wrote, his life had been shaken by paranormal occurrences, from disturbing nightmares to intense feelings of being watched by an evil presence.

The story of the Dybbuk (pronounced anywhere from dib-ick to dib-ook) is rooted in centuries-old Jewish folklore. However, I am Jewish, and I don’t remember my mother ever telling me and my sister stories about demons or phantoms (though I do recall some shades of mysticism from my upbringing, such as leaving the door open for the spirit of Elijah on Passover and protecting our home from evil with a mezuzah). When I first heard this Dybbuk story, I was intrigued by a corner of my own culture that I didn’t know much about. What I found was a trove of fascinating—sometimes dark—folklore that has improbably found its way into the modern world.

By 2012, Mannis’s so-called “Dybbuk Box” gained so much notoriety that the Evil Dead filmmaker Sam Raimi produced a horror movie, The Possession, based on the story. Later, the cabinet itself was sold to Ghost Adventures host Zak Bagans to display in his Haunted Museum in Las Vegas. More recently, fans of the rapper Post Malone blamed an outbreak of bad luck—including an emergency landing of his private jet—on his interaction with the Dybbuk Box.

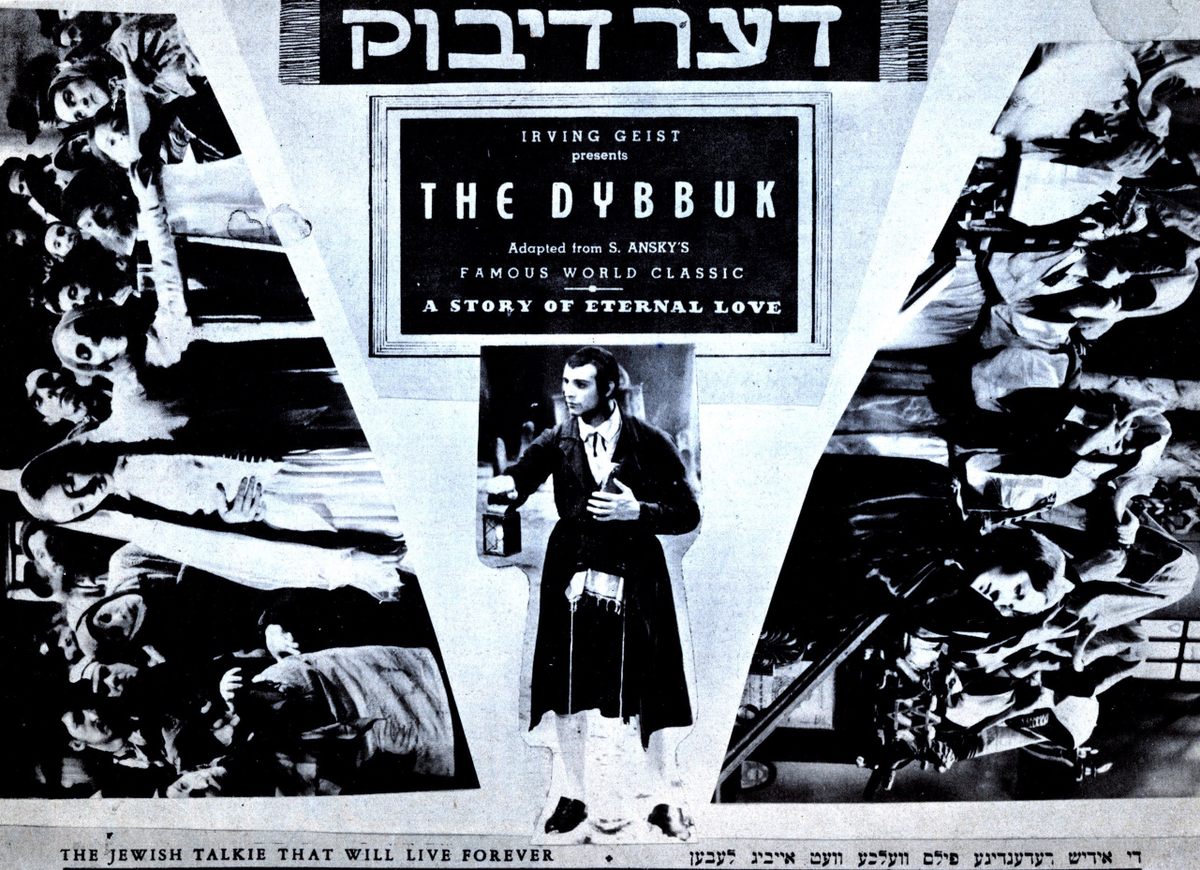

The Possession is not the first dramatized version of a Dybbuk incident. In 1920, folklorist Shloyme Zanvl Rappoport, writing under the name S. Ansky, premiered his play The Dybbuk in Warsaw, Poland. It depicts the haunting of a young woman by the spirit of her deceased lover and has since become a canonical piece of Yiddish literature. The Dybbuk has since undergone dozens of iterations, including a 1937 film and a ballet created by Jerome Robbins and Leonard Bernstein.

In 2021, Mannis finally admitted that his haunted box was a straight-up hoax. He told a reporter from Input that he made the whole thing up as an “interactive horror story in real-time.” Around the same time, there was a wave of people “exposing” and “debunking” so-called Dybbuk boxes on TikTok and other social media sites. Skeptics dismissed the trend as trivializing Jewish tradition. As Zo Jacobi of Jewitches wrote in a blog post, “… it takes almost no research into actual Jewish mythology and folklore to understand and learn that there is no historical basis for [the existence of Dybbuk boxes], but rather a far more modern thirst for sensationalism …”

The origins of demons such as the Dybukk lie in the Talmud, a 1,500-or-so-year-old text that is central to Rabbinic Judaism, and compiles a traditional guide for life—philosophy, history, folklore, and more. According to the folkloric portions of the Talmud, spirits are a constant presence in the human realm, and are there to remind people to live virtuously. As educator and artist Debbie Lechtman points out, many of the stories that make up this Jewish folklore go back much further than the Talmud. “A lot of these ideas in Jewish folklore tied directly back to stories that were being passed down for thousands of years,” she says. “There are so many rich stories that were developed throughout the Diaspora.”

The Dybbuk is one in a menagerie of supernatural beings, alongside Lillith, the Golem, and others who first appear in writing in the Talmud. Over time, many of these beings became closely associated with Kabbalah, a sect of mystical Judaism with medieval roots. (Perhaps not surprisingly, a number of celebrities have been associated with Kabbalistic practice, including Ariana Grande, Ashton Kutcher, and, most famously, Madonna).

In the Talmud, evil spirits are generally referred to as ru’aḥ tezazit. The term “Dybbuk” is a more recent creation. According to Yossi Chajes, director of the Center for the Study of Jewish Cultures and a professor at the University of Haifa, “Dybbuk” is Yiddish in origin. The proliferation of stories around it coincides with the 16th- and 17th-century rise of Jewish mysticism in Eastern Europe.

“The Dybbuk is the soul of someone who has died and, rather than moving on in the afterlife, that soul has lodged itself in the body of a living person,” says Chajes, author of Between Worlds: Dybbuks, Exorcists, and Early Modern Judaism. “It’s a variation on the phenomenon of spirit possession, which exists in nearly every human culture we know of.

“In just about every case, the victim has done something to make them vulnerable,” Chajes continues. “The Dybbuk doesn’t usually inhabit an upstanding individual who is perfectly righteous.” Chajes notes that there is a gendered dynamic to these possessions as well: The Dybbuk is typically male, the victim female. If you feel like you’ve heard the general outlines of this story, know that Catholicism does not have a monopoly on exorcisms. The only way to banish a Dybbuk is by undergoing an exorcism performed by a rabbi.

Dybbuk stories generally have some kind of moral. “The rabbis recorded the stories for a reason,” says Chajes. “They exemplified an issue that they believed needed to be publicized in their communities.” Written accounts of Dybbuk possessions vary but are united by descriptions of the victim’s suffering, as exemplified by case studies in Chajes’s book. In a collection of writings meant to scare people into behaving properly, 16th-century rabbi R. Judah Hallewa described a “young boy [who] began collapsing and uttering strange prophecies,” following a possession in what is now Safed, Israel.

Typically, possession is a “kidnapping or ransom phenomenon, where the Dybbuk is able to threaten the life of its host,” says Chajes. In exchange, the Dybbuk receives passage from the human world to a metaphysical one. In some cases, the rabbi successfully rids the victim of the spirit and allows the Dybbuk to move on to an afterlife, despite the sins it had committed. There is, after all, no eternal damnation in Judaism. “But quite a few of them end with the death of the victim and failure of the exorcist,” says Chajes, in which case “the moral of the story is still loud and clear—the Dybbuk has done something terribly wrong, and the victim has to pay the price.”

Today, the Dybbuk is not necessarily a widely known supernatural figure like the demons of Catholic possessions, despite its deep historical roots. “There are all these beings described in the Talmud, and clearly not all of them are believed [in], and certainly not adhered to,” says University of Connecticut anthropologist Richard Sosis. Violent persecution during witch trials, the Inquisition, and Eastern European pogroms, as well as the proliferation of antisemitic tropes in mainstream European folklore (take, for example, the big-nosed, child-eating villain of Hansel and Gretel) and the rise of skepticism during the Enlightenment, all contributed to the suppression of these traditions. Indeed, for safety, many Jewish communities across the world kept their stories and customs secret.

Lechtman recounts a story from her own childhood growing up in Costa Rica, which she also wrote about in her book, The Witches of Escazú and Other Jewish Fairytales. She says that the ancestors of many of the Jewish people in her town migrated there during the Spanish Inquisition. Even away from Spain, they had to keep their traditions hidden. “The idea was that people would see Jewish women lighting the Shabbat candles through the window and think they were doing witchcraft,” she says, “and to this day, the city’s nickname is the ‘City of Witches.’ Many non-Jewish people have no idea where that comes from, but the Jewish community has passed this down.”

Even though the time of the Dybbuk has mostly ended, despite its social media and Hollywood resurrection, some superstitions remain, and supernatural forces are still felt in various Jewish communities. Some observant Jews in Israel continue to believe in a specific demon known as the ruach ra’ah, and Sosis argues that this spirit has continued to persist because of its association with daily hand-washing rituals.

Lechtman says that part of her motivation for writing her book was to show the diversity of how Jewish people see themselves. “The stories that were told about us for a very long time were pretty terrible,” she says. “So, there’s definitely power in having our own stories.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook