Eat Like a 19th-Century Lumberjack With This Recipe

“One can work harder and longer on pork and beans…than on any other food with which I am acquainted, save bear meat.”

Gastro Obscura’s Summer Cookout columnist Paula Marcoux is a food historian and the author of Cooking With Fire. Throughout the summer, she’ll be sharing recipes and stories from the luminous history of open-fire cooking.

Deep in the mid-winter Maine woods in 1902, a young chemist persuaded six lumberjacks to be his lab rats. For one 18-meal work-week, he cataloged every scrap of food the men were about to eat, then he collected all the relevant feces, sealing them in “museum jars” and freezing them in a snowbank cache. With the cooperation of the camp cook, he also assembled and froze samples of every type of food served to the men. He then transported all these icy jars to the Maine Agricultural Experiment Station at the University of Maine at Orono for analysis.

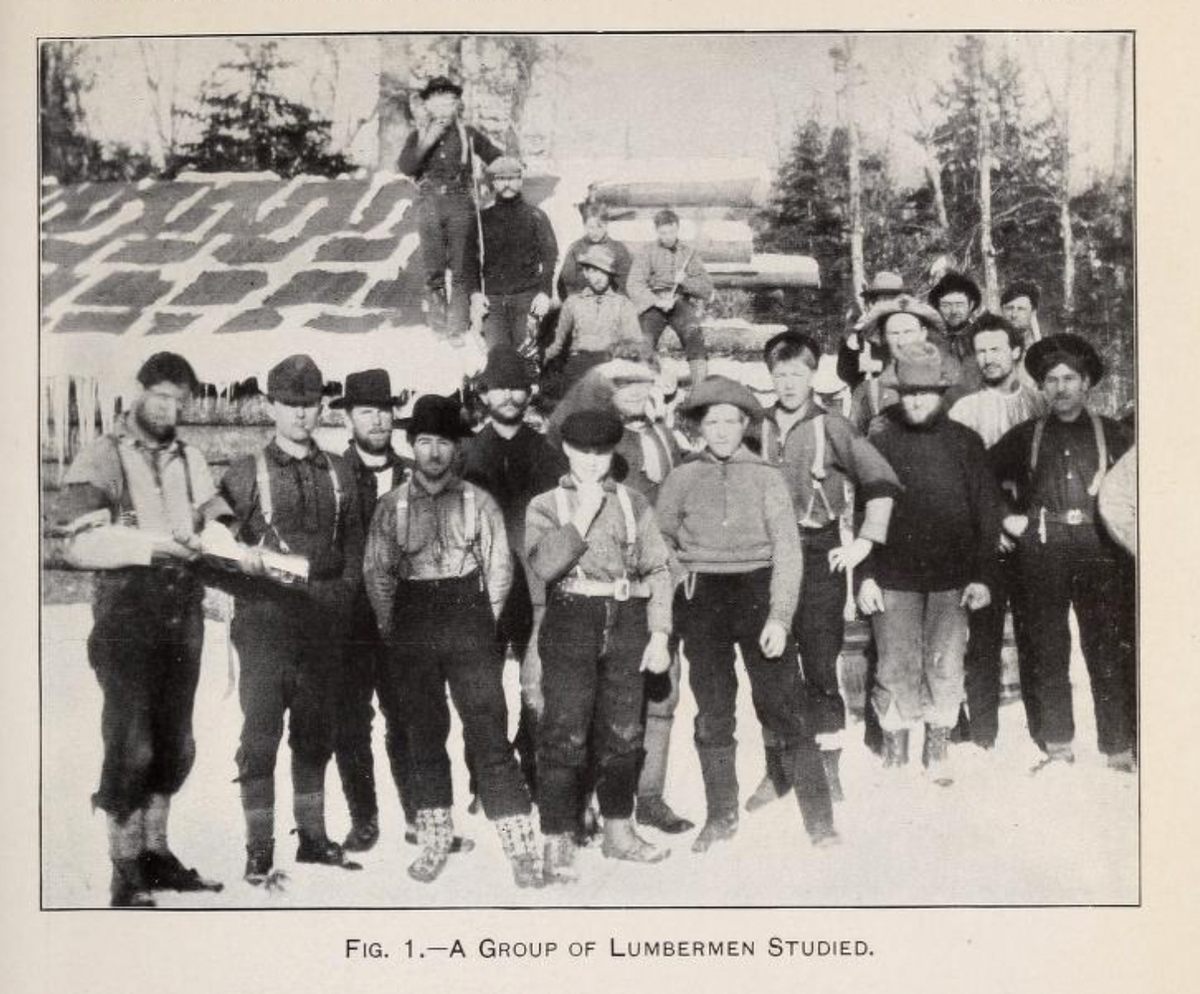

The research was part of an early wave of metabolism and digestion studies that would become foundational to the nascent field of Nutrition Science. But it also provides an incredibly detailed portrait of the diets of lumberjacks at the turn of the century. The study’s subjects were Canadian migrants in their late 20s who were supremely physically fit, spending long days doing “severe work under more or less trying conditions,” as the study’s authors put it.

To fuel that intense labor, the loggers had a calorie-rich, protein-packed diet. Beef and pork, fresh or salted—as stews, boiled meat or roasts—and salted fish—cod, herring and salmon—made their rounds through the menus, accompanied by dishes of potatoes, cabbage, and turnips. Hot breads, especially sourdough biscuits, were in constant supply, as well as doughnuts, pies, cakes, and cookies. But when it came to “the most important single article of diet,” the study identified one dish that stood above the rest: baked beans.

All of these hearty, nutrient-dense foods had been staples throughout 19th-century America, but as the 20th century dawned, the “coarse fare” that was still the backbone of rural diets was increasingly marginalized by “respectable” indoor people. Baked beans epitomized the very coarsest fare imaginable to most Americans, and they ruled the logging camp.

Baked beans had a long history in New England before capitalists used them as a tool to support its deforestation, but in no context were they as indispensable and ubiquitous as in logging camps. They were on the table, in quantity, at two meals daily, minimum. When Henry David Thoreau passed through backwoods Maine 50 years earlier, before the railways eased the challenges of supplying camps, he learned of the much scantier and less reliable diet for loggers—tea, molasses, hard bread, salt pork (sometimes raw), and beans, lots of beans. He observed dryly: “A great proportion of the beans raised in Massachusetts find their market here.” In the interval between Thoreau’s visits and the University of Maine’s science experiment, not only were hundreds of miles of rail laid, but farmers opened clearings along the rivers, planting beans, potatoes, corn, and turnips, and raising dairy and meat animals, all to supply the ready market of the lumber camps.

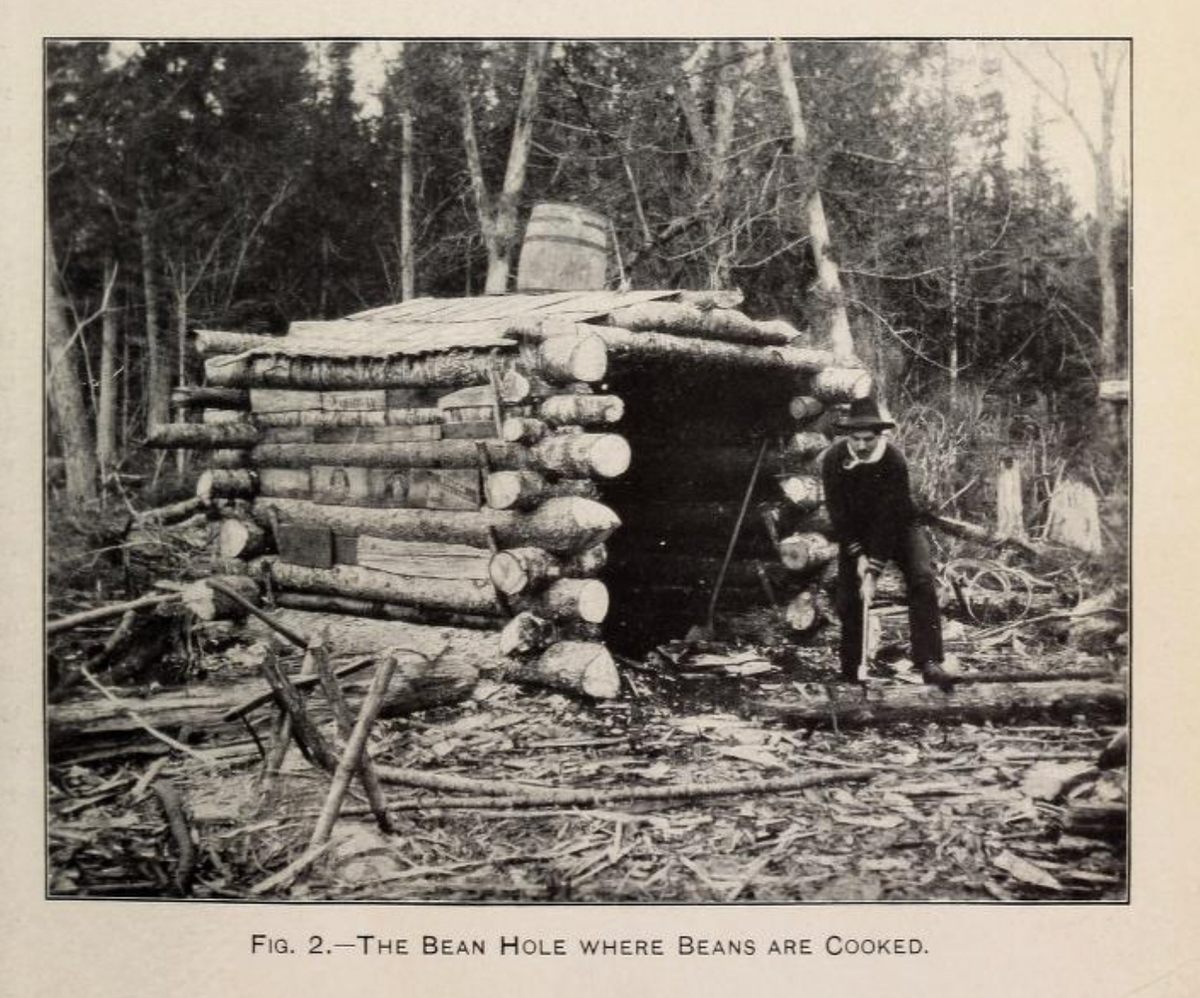

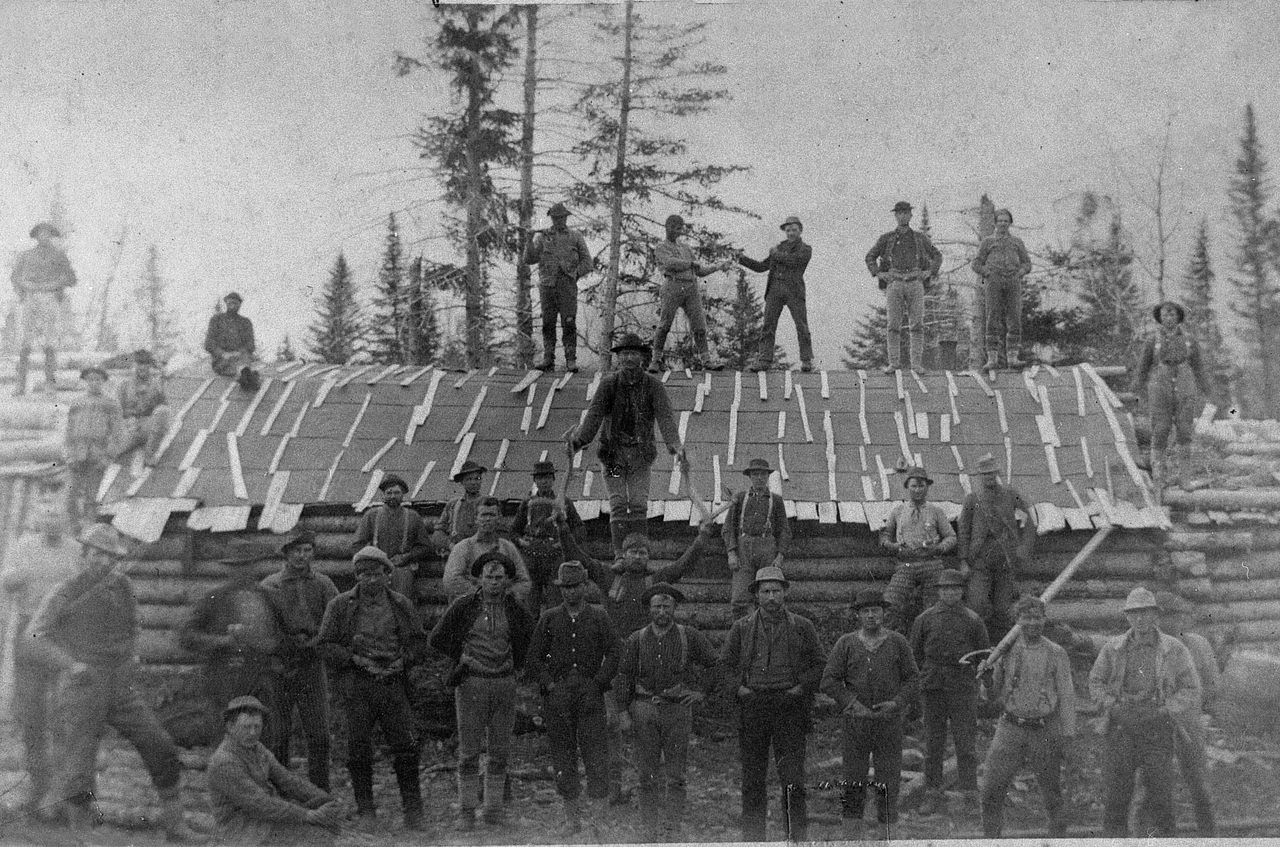

The lumber camp and the bean-hole

While a single, long, log-built structure provided virtually all the domestic accommodation for a 50- to 60-man camp—dormitory, cookroom, dining hall, and food storage—only one daily function, besides the outhouse, warranted its own structure, and that was the lean-to protecting the bean-hole. Each day a cookee (the cook’s helper) would fire up the pit and parboil a batch of soaked beans over the cookroom fire—just until the skin would wrinkle when blown upon. He’d then layer them in the bean kettle with salt pork, onions, and maybe dry mustard, drizzle on a big spoonful of molasses, put the lid on tight, bury the kettle in the bean-hole under hot coals and dirt, and leave it to be dug up before breakfast next day. Then, he’d do it all again.

Much has been written over the last century about lumberjacks, including that they ate a lot of beans, but many of these accounts come in anecdotal form burnished by a nostalgic romance (or, perhaps more correctly, bro-mance, a sedentary and selective perspective on the vanished days of manly men doing manly things). In any case, even if the source is legit, numbers are invariably lacking.

The University of Maine study, first published in a 1904 USDA bulletin and entitled “Studies of the Food of Maine Lumbermen,” is the opposite of that. Despite the fact that the researchers were a couple decades too early to know what a vitamin was, their study was well-designed and the resulting data is an utter trove for the food historian. Granted, it shows that, yes, the loggers did eat a lot of beans, but it gets way more interesting once quantified. Despite the ample and varied meat on the table, and pyramids of doughnuts and sugar cookies, beans were easily demonstrated to be the principle calorie-provider for every man in the study. This was the case even though personal tastes clearly differed: Even if this lumberjack ate tons of protein and that one had a sweet tooth, they all ate strikingly similar weights of baked beans each day, from a pound to a pound and a half, furnishing from 10 to 16 percent of their 6,000 to 8,000 daily calories and one-fifth to one-third of their protein intake.

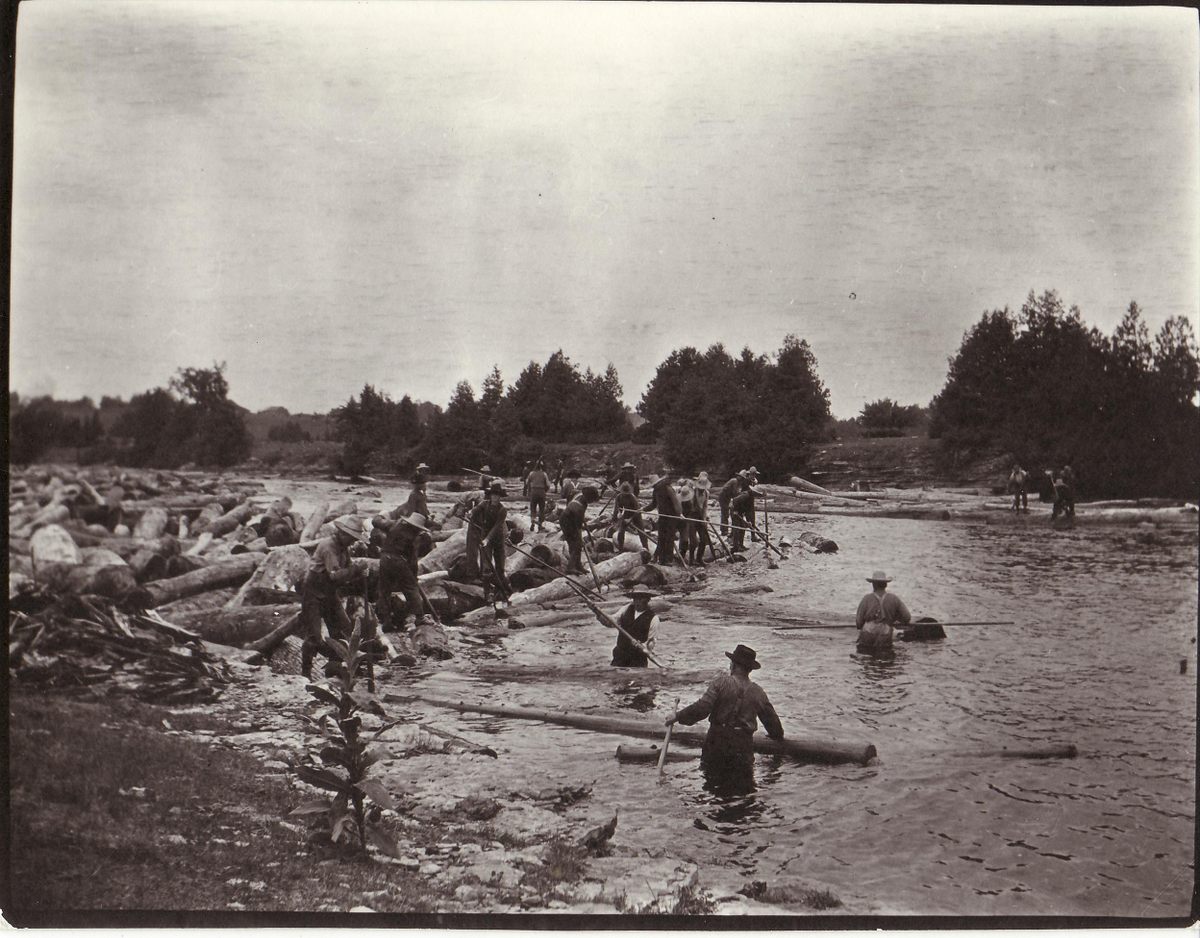

The river drive, when a crew was out working for 10 days or so guiding the logs down the river as the ice broke up, was the most mentally and physically demanding, and the most downright dangerous, part of the job. Even the off-work hours were dreadful, as the men—often soaked to the skin—slept in tents in freezing temperatures. Working from before dawn until late into the night, the men would be brought food at several-hour intervals, eating wherever they happened to stand when the cookees found them.

It was during this most punishing phase of the operation that baked beans were crucial, as they comprised the main component of the diet, accompanied only by sourdough biscuits, cookies, tea, and molasses, up to five meals a day. As the study’s authors observed, “These conditions might naturally tend to lessen the appetite.” Without a full menu of meat dishes and pastry, the men ate 25 percent less food overall, and generally lost a few pounds from their already lean frames. Baked beans supplied most of the calories and protein to keep them going.

As old-school logging camps and river drives became obsolete in Maine in the late 20th century, bean-hole beans gained a new generation of adherents among outdoorsmen and women, whose interests aligned more closely with Thoreau’s half a century earlier, than with the loggers of 1902. Authors of hunting and fishing manuals as well as scouting guides promulgated the bean-hole technique, but not without a note of caution to tenderfoots:

Baked beans are strong food, ideal for active men in cold weather. One can work harder and longer on pork and beans, without feeling hungry, than on any other food with which I am acquainted, save bear meat. The ingredients are compact and easy to transport; they keep indefinitely in any weather. But when one is only beginning camp life he should be careful not to overload his stomach with beans, for they are rather indigestible until you have toned up your stomach by hearty exercise in the open air.

–The Book of Camping and Woodcraft: A Guidebook for Those who Travel in the Wilderness, by Horace Kephart)

Armed with that admonition, a heavy kettle, a shovel, and a few other oddments, you too could be digging up your breakfast tomorrow.

Bean-hole Beans

Timing

Start 24 hours before you’d like to dig up and serve these beans. While this may seem like a lot of commitment, remember that the final 16 hours or so require nothing whatsoever from the cook, as the magic happens underground while you sleep or party or whatever it takes to work up a lumberjack’s appetite.

Gear

You’ll need a large cast-iron pot with a bail and a heavy, snug-fitting lid, and fire-tending and digging tools. If the lid of your pot is at all loose or lightweight, or if you’re a Nervous Nellie like me, by all means find something to act as an additional barrier to prevent sand, dirt, or ashes from finding their way inside. On various occasions, I’ve used the lid to a large enamel pot, a weird scrap of aluminum, and a pile of ferns topped with old shingles; I’ve read one outdoorsman-guide recipe that suggested making a flour-and-water paste gasket for your bean kettle.

For fuel you want a mix of hard and softwood, dry and split fairly small.

Ingredients

Beans. We old-timey New Englanders love our Marfax, Yellow Eye, Jacob’s Cattle, and Soldier beans, but you can use Navy, Great Northern, or Cannellini, or really any full-flavored, sturdy bean you like.

Salt pork. This savor-bomb is responsible for the distinctive richness intrinsic to traditional New England beans, regardless of baking technique. Lumber camp cooks used as much as 2½ pounds of salt pork to season 2 pounds of beans; in other settings, a half-pound might be used.

For best results, keep your own salt pork on hand: Rub a chunk of pork belly with kosher salt on all sides, place on a little bed of salt in a sealable tub with a little room to spare around it, and pour over a brine you make by dissolving more salt in cool water until it tastes like sea water. Seal up the tub and refrigerate until needed, cutting off chunks and topping up with new brine to keep it fully submerged.

2 pounds dry beans

½ to 2 teaspoons salt, depending on the amount and saltiness of the salt pork

1 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1 teaspoon dry mustard (optional)

3 tablespoons molasses

1 medium onion, sliced

½ to 2½ pounds salt pork

1. Cover the beans with abundant cool water and let them soak for 6 to 8 hours.

2. Meanwhile, dig the bean-hole. You want to be able to manipulate the kettle into and out of the bean-hole easily, with just the right amount of space on all sides for hot coals and dirt. So plan on a level-bottomed cylindrical pit, at least a foot deeper than the height of your bean-kettle, and about twice its diameter. If you plan to line the bottom and the perimeter of the pit with stones, which is optional but nice, account for that as you dig.

3. Kindle the fire about 18 hours before you wish to serve the beans. Starting a fire in a clammy narrow pit can be challenging, so go easy on yourself by having plenty of nice dry tinder and kindling wood. At lumber camps, where a bean-hole would be protected from the weather by a lean-to and was used day in and day out, this process would be relatively quick and easy. Heating a newly-dug bean-hole in damp conditions on the trail can be another story.

One period author—a trapper—mentions this useful trick: Make a lattice of green sticks across the mouth of the pit, create a “cob-house” (an airy stack layered at right angles like a log cabin) of dry sticks atop it, and set that alight. Add more fuel as you can, and eventually the whole thing will collapse into the pit and away you go. Whether or not you use this technique, once your fire has caught, burn it steadily at a moderate pace for about 2 hours. A mix of hard and softwood works great.

4. To parboil the soaked beans, add water, if necessary, to cover by two inches. Place them over a medium flame and bring to a very gentle simmer, skimming the froth. Cover and cook very gently until the skins of the beans wrinkle when you dredge up a few and blow on them. This generally takes at least an hour, but depends entirely on the age and quality of the beans.

5. Slice the onion and toss on the bottom of the bean-kettle. Ladle over about half of the beans. Either cut the pork in slices, or leave whole, cross-hatching slashes into the rind with a knife. Add the pork to the pot, then layer in the remaining beans, saving the broth.

6. Place the salt, pepper, optional mustard, and molasses in a small bowl. Ladle in some of the bean broth and stir to combine. Pour over the whole thing, and finish with more of the bean broth (or boiling water if you run out), enough to cover the top beans by nearly an inch. Heat over a low fire so that it will be at a simmer as it goes into the ground.

7. If you are nervous about the security of your pot lid, now is the time to act. You can jury-rig a protective “helmet” as described in the “Gear” note above, or you can make a sacrificial gasket by stirring together a very thick slurry of flour and water and pasting along the lip of the lid to seal it.

8. Meanwhile, gather everything you’ll need to get the kettle cleanly into the hole and covered up. When everything is ready, use a long shovel or fire tongs to pluck out any large chunks of unburned wood. Push smaller coals and embers to the perimeter of the pit, so that the kettle will rest securely upright at the bottom, and carefully lower it into the center. (If the pit is unlined, and there’s a lot of loose hot earth and ashes, dig some out first, piling it nearby so that you can quickly nestle it around the pot.)

Some authors advise packing plant material around and over the pot at this point; I have enjoyed adding a thick layer of green bracken but cannot swear that it made a difference in the result. Laying in a piece of sheet metal or a thin layer of clapboards before the dirt goes over has also been known to mollify the worry-warts amongst us. At any rate, mound the bean-bake over with earth.

9. Let the beans bake for at least 12 hours; longer is fine in our experience. When you dig the pot up, try to be mindful of the dirt at each turn. Carefully avoid disturbing your protective barriers prematurely. A small hand broom is helpful.

As good as these beans are right away, they’re even better reheated if there are any left over.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook