Competitive Eating Was Even More Gluttonous and Disgusting in the 17th Century

For the Great Eater of Kent, it was all ale-soaked bread and wheelbarrows of tripe.

In recent years, the “sport” of competitive eating has gained greater and greater popularity, and even produced its own small band of celebrity competitors. But centuries before the antics of Takeru Kobayashi, or the dominance of hot dog champion Joey Chestnut (72 in 10 minutes on July 4, his tenth title in 11 years), there was Nicholas Wood, the Great Eater of Kent, who may just be one of the earliest examples we have of a true competitive eater.

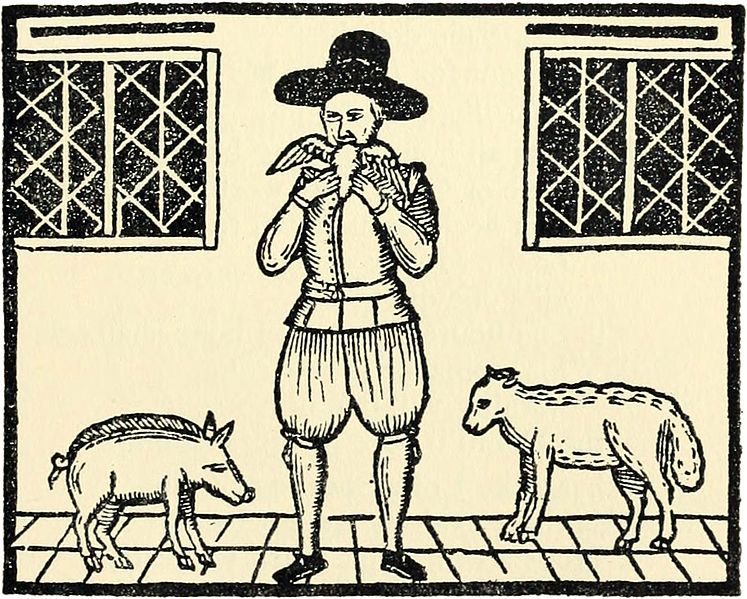

Most of what we know of this proletarian hero comes from an account of his career written by the English poet John Taylor, who later became Wood’s representative. The pamphlet, called The Great Eater, of Kent, or Part of the Admirable Teeth and Stomach Exploits of Nicholas Wood, of Harrisom in the County of Kent His Excessive Manner of Eating Without Manners, In Strange and True Manner Described, was written to promote an eating exhibition that never came to pass.

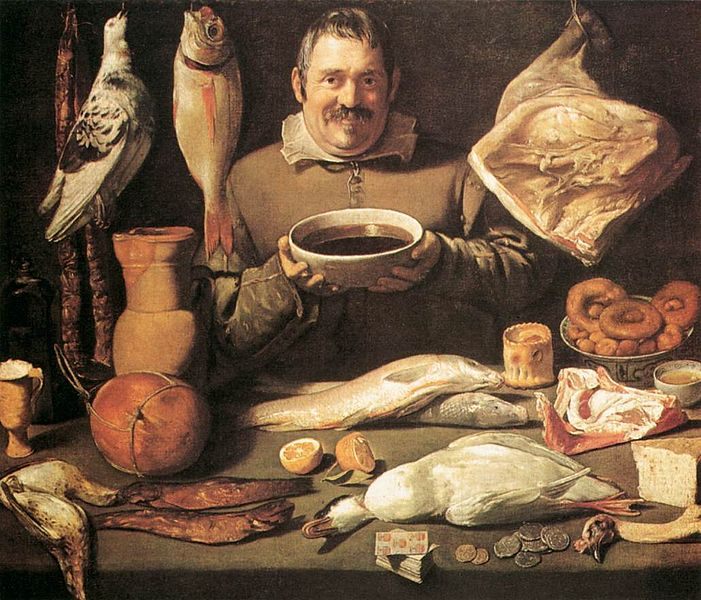

Before he came to be known by his more colorful nickname, it seems that the Great Eater was a regular 17th-century guy named Nicholas Wood. As the story goes, Taylor encountered Wood in an inn in Kent, and was amazed to see him devour some 60 eggs, a good portion of a lamb, and a handful of pies—a meal that left him hungry for more.

Wood was a farmer when Taylor found him, but the Great Eater had already gained a reputation as a nearly superhuman feaster. Wood made a name for himself as a glutton by performing feats of feasting at fairs and festivals, as well as by taking part in dares and wagers with nobles. As recounted in Jan Bondeson’s book, The Two-Headed Boy, and Other Medical Marvels, Wood had, at various times, devoured such incredible meals as seven dozen rabbits in one sitting, or an entire dinner feast intended for eight people.

Wood’s reputation was impressive, but he was far from undefeated. On at least two occasions, he was in fact beaten by food. During a visit with a man named Sir William Sedley, Wood ate so much that he fell over and went into a serious food coma. Upon Wood’s awakening the next day, Sedley had his men put him in the stocks to shame him for his failure. In another instance, a man named John Dale bet that he could sate Wood’s appetite for just two shillings. Wood took the bet, and Dale fed him 12 loaves of bread that he’d soaked in a strong ale. If it wasn’t the sheer bloating effect of such a terrifying meal that did Wood in, it was the ale, which got him so drunk that he passed out. Dale won the bet, and Wood was once again humiliated.

Yet despite these instances of completely understandable weakness, Wood’s reputation as an eater kept bouncing back, and he maintained a sort of celebrity in Kent. After Taylor witnessed his incredible fortitude at that inn, the poet decided that they could both make some money on Wood’s voracious appetite. As recounted in his very own pamphlet, Taylor offered Wood payment, lodging, and massive amounts of food should he agree to come stay with him for a time in London. Wood had never traveled to London, and Taylor saw an untapped audience for the glutton’s talents.

Taylor’s plan would have had Wood perform daily feats of overeating at the city’s Bear Gardens, which at the time hosted animal fights. Among the suggested meals to give the “most exorbitant paunchmonger” were a wheelbarrow full of tripe, as many puddings as would stretch across the Thames, and an entire fat calf or sheep.

For better or worse, this gluttony exhibition never came to pass, as Wood, who was getting on in years, and who had lost all but one of his teeth from eating an entire mutton shoulder—bones and all—declined Taylor’s offer, saying that he wasn’t sure he’d be able to perform to expectations.

Even though Wood bowed out of what could have been the exhibition of his life, Taylor did not seem to bear him any ill will. A large portion of Taylor’s hagiography of Wood is spent comparing his monumental feats of gluttony to the achievements of historic giants such as Charlemagne and Alexander the Great: “Therefore this noble Eatalian doth well deserve the title of Great. Wherefore I instile him Nicholas the Great (Eater). And as these forenamed Greats have overthrown and wasted countries, and hosts of men, with the help of their soldiers and followers; so hath our Nick the Great, (in his own person) without the help or aide of any man, overcome, conquered, and devoured in one week, as much as would have sufficed a reasonable and sufficient army in a day[.]” The poet’s florid description of Wood gives him such names as “Duke All-Paunch” and the “Kentish Tenterbelly.” Even as his talents faded, it’s clear that Taylor still saw Wood as a champion.

As for Wood himself, according to Bondeson, the Great Eater left Taylor’s house one day and was never heard from again. He slipped away into the fog of history, and yet our love of monstrous appetites has survived him pretty much intact.

This story originally ran on February 21, 2017.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook