How the 1878 Eclipse Almost Killed the Father of American Meteorology

Today’s National Weather Service might be very different if Cleveland Abbe had died on Pikes Peak.

Millions of North Americans are expected to (carefully!) turn their eyes to the sky on April 8 to witness a total eclipse of the Sun that will cross North America from shore to shore. Eclipse madness has taken hold. But while such anticipation can be thrilling, it can also be dangerous. In fact, during a solar eclipse in 1878, the fervor to witness the event almost cost the nation arguably its most influential meteorologist.

In 1878, crowds from all across the country gathered in a path of totality that spanned from Montana to Texas. In addition to the tourists who traveled specifically to experience the celestial event, many of the scientific luminaries of the day also made the journey. Thomas Edison headed to the Wyoming Territory to test out his new tasimeter, an early attempt at detecting infrared radiation. Other groups of scientists headed to locations nearer the ends of the path in Texas or Montana. But the lion’s share of astronomers and scientists traveled to Colorado.

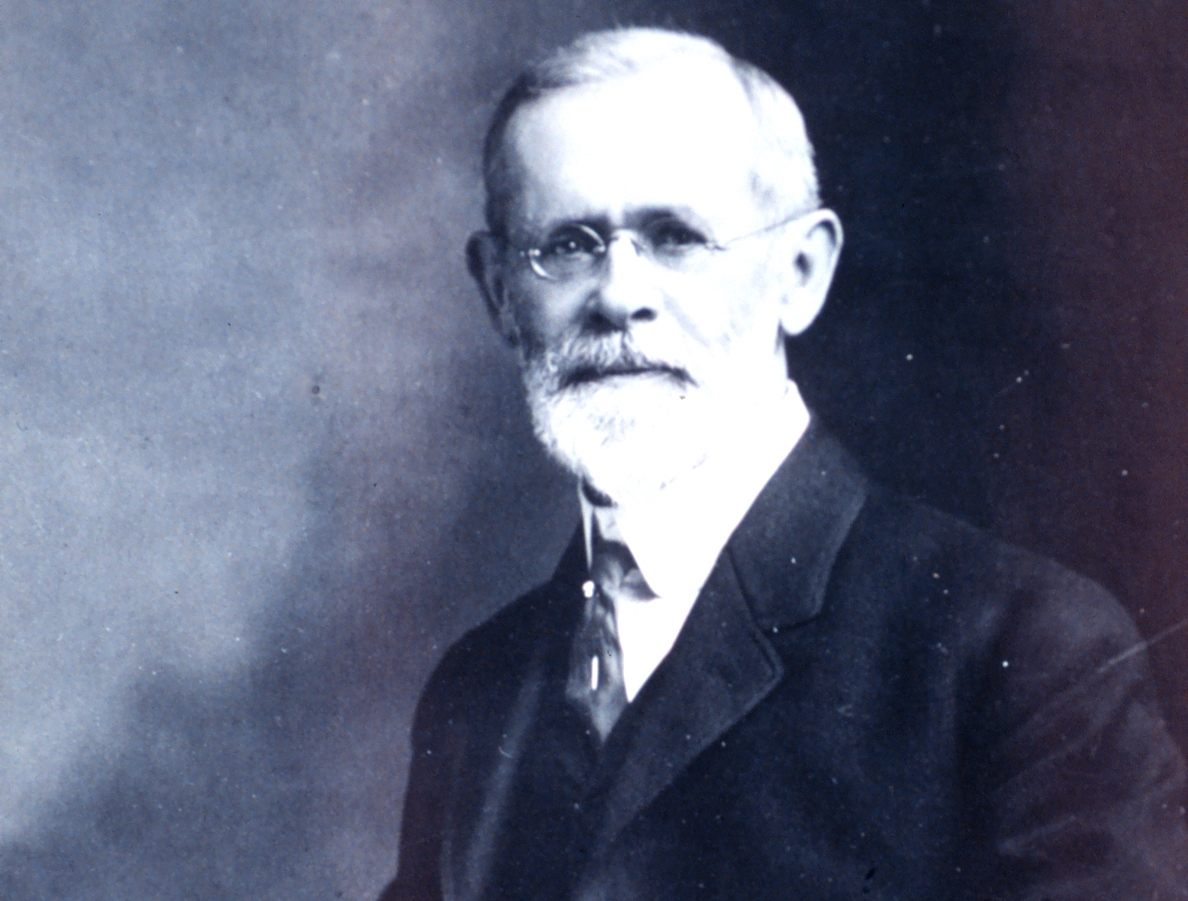

One group of researchers made their way to the summit of Colorado’s Pikes Peak. This group included Cleveland Abbe, who is today known as the father of the National Weather Service. “He was trained as an astronomer, but he became a meteorologist, and he became the first weather forecaster for the U.S. government,” says David Baron, author of American Eclipse: A Nation’s Race to Catch the Shadow of the Moon and Win the Glory of the World. “He climbed Pikes Peak in 1878 to witness the eclipse and nearly died.”

Abbe began his professional career as an astronomer, becoming director of the Cincinnati Observatory in 1868. But he soon became better known for his daily weather forecasts, the first such private predictions in the nation, which he would create based on climate information telegraphed from outside observation stations. As he provided them to Cincinnati newspapers and other subscribers, they earned him the terrific nickname “Old Probabilities,” or “Old Probs.”

When the cash-strapped Cincinnati Observatory could not afford to maintain Abbe’s meteorological soothsaying, he moved his operation to Washington, D.C., under the auspices of the brand new United States Weather Bureau, of which he was made the first chief meteorologist. The bureau was part of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, which was the official body in charge of monitoring the country’s weather. Under this new meteorological body, Abbe gave his first official weather report in 1871, and quickly became the leading meteorologist in the country.

So when the 1878 eclipse appeared on the horizon, excited astronomers turned to the Weather Bureau to locate the ideal place to witness the event, where weather conditions would be least likely to block their observations. Using historical weather data about the regions in the path of the coming eclipse, Abbe had the Signal Corps send out a circular that outlined some possible viewing sites. But as Baron describes him in his book, Abbe was still a “frustrated astronomer,” and he didn’t want to miss such an amazing celestial sight. Neither did his boss, General Albert Myer, who had witnessed an eclipse in Virginia in 1869.

Myer had viewed that earlier eclipse from a height of around 5,000 feet, and so decided he wanted to witness the 1878 eclipse from somewhere even higher. He chose Pikes Peak, an ultra-prominence with a summit at over 14,000 feet above sea level, which sat right in the middle of the eclipse’s path and also had a hardscrabble meteorological station on top. When Abbe asked if he could go West to view the eclipse, Myer agreed.

“The scientists who got up there about a week in advance had just a hell of a time,” says Baron. Abbe got to Colorado Springs, at the base of the peak, on July 20, and was joined by fellow astronomer Samuel Pierpont Langley, plus Langley’s brother, and over a thousand pounds of equipment. The men of the Signal Corps were reportedly nonplussed by all of the surprise science work, but made their way some 18 miles up the mountain to the observation station with the help of some burros.

Over the next week or so, Abbe and his colleagues were battered with wind, cold, and extreme weather as they tried to observe the skies in preparation for the eclipse. But that wasn’t the worst of it. “They were battling snowstorms in July that threatened to rust out their telescopes. They also suffered significant altitude sickness,” says Baron. Due to the extreme difference in air pressure and lack of oxygen at such a high altitude, the astronomers experienced headaches, dizziness, and disorientation. Many people can adjust to altitude sickness, but that was not the case for Cleveland Abbe.

The day before the eclipse, Abbe woke to pain so extreme he could not stand. The Langleys tried to convince Abbe to go down the mountain, but he refused, holing up in his tent, insisting that he could recover. Later that evening, General Myers finally made his way to the peak, where he ordered Abbe taken off the peak on a stretcher.

And it’s a good thing he did. “I ran [the story] by an expert in altitude medicine here in Colorado, and he agreed, it’s pretty clear that Cleveland Abbe had high altitude cerebral edema,” says Baron. “His brain was swelling and pressing on the inside of his skull. It’s the sort of thing where, had he spent another night up on the top of Pikes Peak, he could very well have died.”

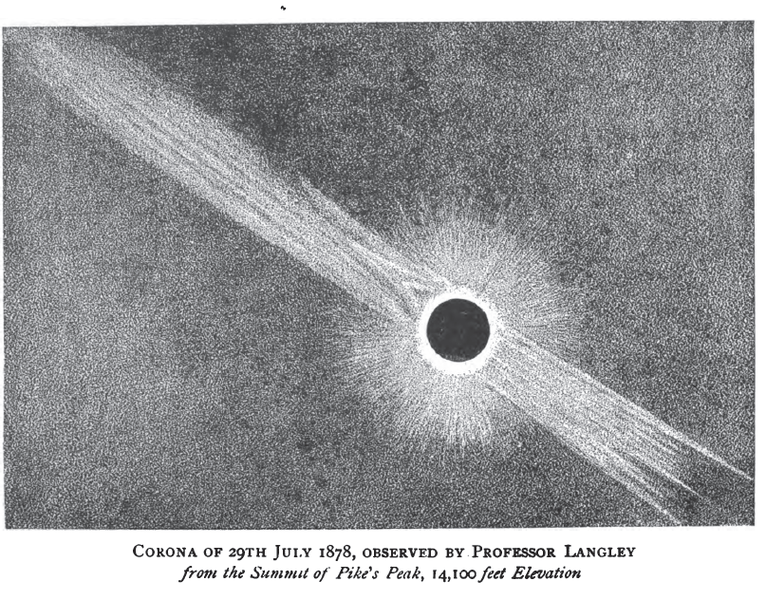

Abbe was carried down the mountain to a lodge that sat just below the tree line. A doctor arrived at the lodge and forbade Abbe from returning to the peak for the eclipse, but all was not lost for the pioneering weatherman. The next day, the skies over the mountain had miraculously cleared, and Abbe was able to convince his caretakers to carry him out and lay him on a slope where he could witness the totality with his own eyes. There, presented on the slope like a sacrifice to celestial mechanics, Abbe was able to see the moon pass in front of the sun, shooting vivid daggers of light off the ring of the corona.

Up at the summit, Myer and the Langleys got their own show. “First of all, they got to see the eclipse itself with amazing clarity, because there was less atmosphere to look through,” says Baron. “The outer atmosphere was just dazzling. But from that altitude, not only were they able to look up and see the eclipse, they were able to look out and look down, and actually see the moon’s shadow coming toward them.”

Abbe, Myer, and the Langleys all made it off the mountain, each going on to notable careers in their fields. Abbe returned to the Weather Bureau and worked to keep it at the forefront of meteorological advances during his tenure, before returning to academia in his later years.

The National Weather Bureau continued to evolve after Abbe’s passing in 1916, eventually becoming the National Weather Service that sends us texts about flash floods and studies our shifting climate today. But it could all have been sidelined by the Colorado eclipse.

This piece was originally published in 2017 and has been updated as part of Atlas Obscura’s Countdown to the Eclipse, a collection of new stories and curated classics that celebrate the 2024 total solar eclipse and the Ecliptic Festival in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook