The Modern Movement to Exonerate a Notorious Medieval Serial Killer

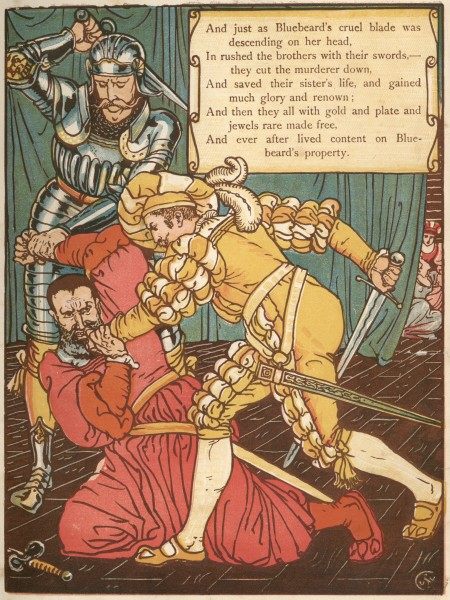

Gilles de Rais inspired the tale of Bluebeard. But was he really a murderer?

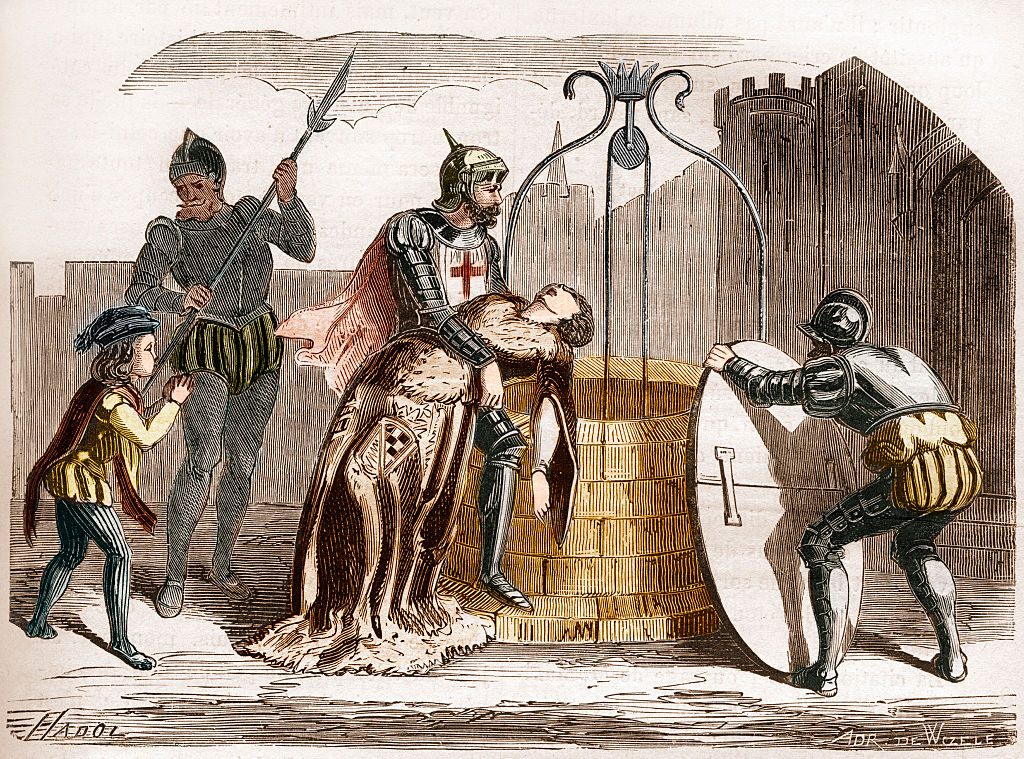

If the name Gilles de Rais rings a bell, you probably know him as the man responsible for the deaths of 150 boys in 15th-century France, degenerate deeds that led to his apotheosis as an early serial killer and the inspiration for the legend of Bluebeard.

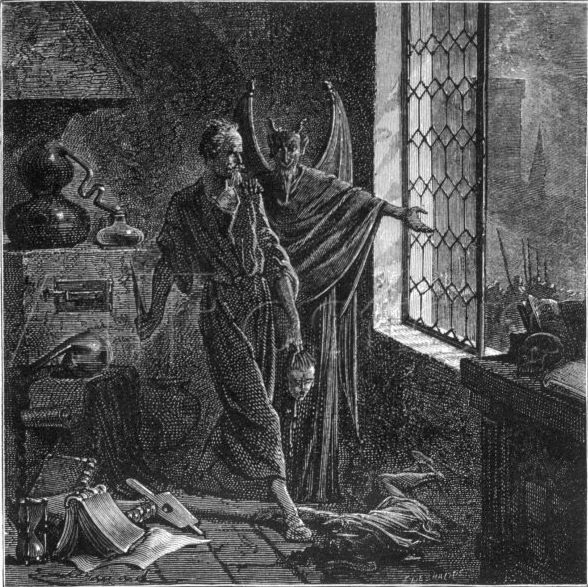

Those with an interest in true crime might be aware of another detail: Rais was a war hero, appointed Marshal of France at age 25, who served alongside Joan of Arc—it’s because of her death, the story goes, that he went mad and turned to heresy, alchemy, and murder.

Brought to trial after dozens of children went missing in the Nantes countryside, Gilles de Rais was accused of, in the words of biographer Georges Bataille, “the abominable and execrable sin of sodomy, in various fashions and with unheard-of perversions that cannot presently be expounded upon by reason of their horror, but that will be disclosed in Latin at the appropriate time and place.” Rais confessed and was summarily executed on the October 16, 1440.

It’s a captivating tale, informing a wealth of books and websites dedicated to a “throat-slitter of women and children, judged for his crimes and burned in Nantes.” (This from Eugène Bossard, another biographer.)

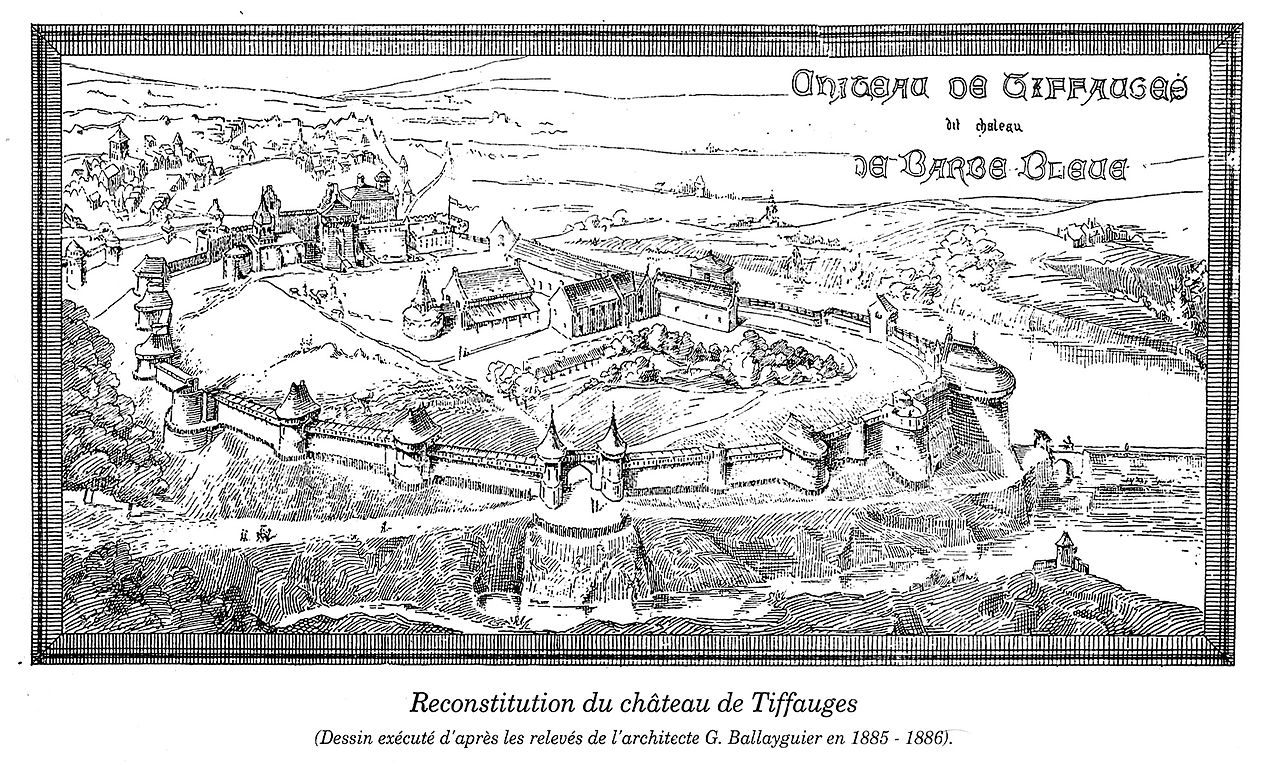

In 1992, the Breton tourist board commissioned a Gilles de Rais biography from French author Gilbert Proteau. The area around Rais’ castles was a travel destination for those wishing to see the crime scenes of a confessed serial murderer, and the board thought a book would bring in more tourists. Instead, Gilles de Rais ou la Gueule de Loup made the case that Rais was innocent—Prouteau also called for a retrial. A Court of Cassation, the highest court of appeals in France, was conducted and Rais was fully exonerated later that year.

This exoneration isn’t a secret: many of Rais’ countrymen know him as the victim of Church conspiracy, falsely accused on account of his great wealth and political connections to Joan of Arc, who herself was tried for heresy and executed 10 years prior. Yet while attempts to clear Rais’ name go back to 1443, the majority of his biographers make little mention of this or of the suspicious circumstances around his trial. Those who have considered the possibility of Rais’ innocence are few and far between—and almost all of them wrote only in French. Add in the pre-Internet Court of Cassation and you’ve got a wealth of information that has remained inaccessible to an English audience. Like a 15th-century Steven Avery, Rais has been waiting for his very own season of Making a Murderer. Now, 600 years after his execution, he may finally be getting it.

Margot K. Juby, a writer living in Cottingham, England, calls herself “Gilles de Rais’ representative on Earth” and is determined to clear his name worldwide. Since 2010, Juby has maintained the website Gilles de Rais Was Innocent, posting links to original documents in English and French and explaining how each myth, from the 150 dead boys to the associations with Bluebeard, began to pass for fact. This year, on the 25th anniversary of the 1992 retrial and Gilles de Rais’ acquittal, she will self-publish what she calls the first accurate biography of Rais in existence—and the only English-language biography to discuss the possibility of his innocence. It’s the product of a lifelong obsession and years of research that started, like many things do, with a book.

As a teenager, Juby discovered Gilles de Rais while reading The Devil And All His Works by Dennis Wheatley. One of the pages depicted a man leaning on a battle-axe; the caption read “Gilles de Rais, one of the blackest sorcerers in history.” Juby was intrigued, and over the next few years began hunting down rare and out-of-print books about Rais, many of which were in French. The more she read, the more convinced she became that he had been framed. In 1992, when the retrial made the front page in Kingston-upon-Hull, where Juby lived at the time, she experienced “the greatest adrenaline jolt of [her] life.”

In England, however, Gilles de Rais’ innocence was short-lived. Prouteau’s biography was never translated, and newspaper headlines were slowly forgotten amid the continued publication of salacious books professing his guilt. Twenty-five years later, Juby’s biography offers another explanation for what really happened in the years leading up to 1440 and which, she hopes, will be one link in the chain that finally restores Gilles de Rais to his proper place in history. Clocking in at over 230 pages, it also attempts to catalog the persistent myths that follow Rais even in death.

“I’m still finding things that are cited as fact in all the biographies that turn out to be based on dust and moonlight,” Juby says. An example is the murder of three children by Rais’ valet Henriet, which appears in the biographies of Bossard and Bataille. Juby looked through the trial records and even checked the Latin transcript—nothing. “Bossard seems to have made that bit up,” she says; Bataille, writing later, swallowed Bossard’s story whole. Indeed, most of Rais’ biographers never even read the original trial records, relying instead on a “more detailed” record written by Paul Lacroix, The Bibliophile Jacob, in the mid-19th century. This version was then absorbed into J-K Huysmans’ novel Là-bas—keyword here being “novel”—and Là-bas, in turn, was reinterpreted as nonfiction by the biographers that followed, resulting in what Juby calls a “posthumous public-relations disaster.”

Even the books that professed Rais’ guilt offered unconvincing reasons. “It seems impossibly quaint in the 21st-century to read a text that fully accepts the validity of an Inquisition trial with the use of torture,” Juby says. Rais’ two judges, Jean de Malestroit and Jean V, Duke of Brittany, were both engaged in business deals with him and would inherit his property in the event of a conviction. Moreover, the physical evidence against him was nonexistent. “What did they find, unearth, discover during their exploration?” Prouteau wrote in Gueule de Loup. “Nothing, not a clue. Not a tooth. Not a trace, not a hair. Not one witness who can say: ‘I have seen.’ Not a weeping mother who claims: ‘There is the dress stained with the blood of my dead daughter.’ Not a father who brings a child’s heart ripped from its chest and wrapped in a spotted cloth.”

For a proposed murderer of 150 children who supposedly killed these children in his own home, this seems incredibly unlikely.

None of this is new information. “I’m not the first or the last to question Gilles’ guilt,” Juby says, naming attempts by King Charles VII in 1443, a pamphleteer during the French Revolution, essayist Salomon Reinach in the 1920s, and biographers Fernand Fleuret and Jean-Pierre Bayard. The trial records alone show identical testimonies, witness accounts that were said to exist but weren’t included, and passages amended after the trial’s end. “It’s my impression that Gilles’ actual guilt is much held in doubt by historians today,” says John D. Hosler, an Associate Professor of History at Morgan State University who specializes in the European Middle Ages and the history of warfare.

“All in all, the affair contains a number of pretty standard medieval tropes and accusations,” from the kidnapping and torture of children to the heresy accusations. “Personally, it all looks highly suspicious to me.” Shocking things like Rais’ alleged crimes do happen, Hosler clarifies; nobody can prove his innocence centuries later, not even Juby. But a critical look at all existing information makes a pretty good case for it.

“We no longer believe the evidence in any of the witch trials,” Juby says. “We no longer believe the Knights Templar were some kind of Satanic cult.” While her initial interest in Rais’ trial may have been borne of an adolescent sense of injustice, it has been sustained by an interest in understanding people’s biases, fact-checking across languages and centuries, and wanting to share her discoveries with the world. “I always had a feeling I was supposed to do something, but I didn’t know what,” she tells me. She still needs to complete an index, and plans to release her book later this year. “I am proud to be Gilles de Rais’ representative on earth.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook