How a Newspaper Hoax Led to Ostrich Racing in Nevada

A seasoned ostrich racer named Shorty (left) takes on the competition at the International Camel & Ostrich Races. (Photo: Rob Wyatt)

On a mid-September morning in the small town of Virginia City, Nevada, a grown man by the name of Shorty climbed onto the back of an ostrich, raised his right arm, and held on for dear life with his left as the bird, wearing a numbered bib, sprinted along a dirt racetrack.

Shorty’s ride was but one component of the annual International Camel & Ostrich Races, a three-day event in which adults race camels, ostriches, and zebras—and children chase emus and chickens.

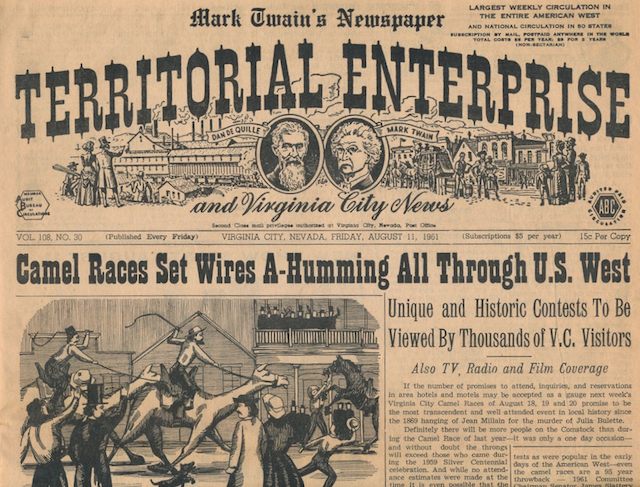

The premise of the event sounds a little like a hoax. In fact, that’s how it all began. In 1959, Virginia City’s Territorial Enterprise newspaper editor Bob Richards published a fake story about upcoming local camel races. The newspaper had been publishing hoax articles since way back in the 1860s, when a local man named Samuel Clemens began writing stories that were often fake, too. Clemens lived in Virginia City from 1861 to 1864, when he adopted a new name: Mark Twain.

Evidently, in response to the 1959 hoax racing article, another paper actually showed up with a herd of camels to compete, and Virginia City was forced to step up. Soon, the International Camel & Ostrich Races were born. They have continued to be held ever since.

Camel racing on the front page of the August 11, 1961 edition of Territorial Enterprise. (Photo: Private collector)

The races weren’t an entirely odd addition to the town. Virginia City, a National Historic Landmark District, does have a camel-rich heritage. After the 1859 discovery of the Comstock Lode attracted a rush of silver prospectors, many sturdy, humped ungulates were used to transport mining material, and a few workers thought it would be a good idea to race them. As a sign of sustained interest in the exotic sport, the Territorial Enterprise published a blurb about camel racing in Algeria in 1899, long after the ore-mining bonanza ended.

Daily Territorial Enterprise, November 7, 1899. (Photo: Cooperative Libraries Automated Network)

Today, the races attract scores of visitors and locals who are eager to bear witness to folks riding exotic animals. The creatures belong to Joe and Sondra Hedrick of Nickerson, Kansas, and for the most part, the animals seem pretty mellow—that is, until the gates open and a race is on. The camel and ostrich races have become so popular that they have moved to a bigger venue: the Virginia City Arena and Fairgrounds, built in early 2015 to accommodate the peculiar display, among other happenings.

As it was when it first officially began, the event involves representatives of rival news outlets racing camels for the win. The ostrich races, on the other hand, require a lot more skill and training on the part of the rider, since getting thrown off and occasionally mauled while riding an ostrich bareback is not uncommon (so you most likely won’t find a reporter racing one of those). Either way, every rider needs to sign a lengthy waiver, just in case.

Children chasing emus at the International Camel & Ostrich Races. (Photo: Rob Wyatt)

The guest of honor at the 2015 International Camel & Ostrich Races was Geno Oliver, an 82-year-old Korean war veteran who has been racing camels and ostriches on and off since 1963. He’s competed in international camel-racing events in Australia and Europe, and even temporarily came out of retirement to compete in the International Camel & Ostrich Races for his 80th birthday two years ago. But again, when it comes to riding camels and ostriches, there’s a big difference. “Camels have a different gait, and an ostrich is strictly balance,” Oliver explains, adding, “I hated racing bareback on ostriches because you’d smell for about four days afterwards, and a camel doesn’t have any sweat glands, so you can ride a camel bareback and you don’t smell.”

Geno Oliver aka General Geno Vino from Reno. (Photo: Rob Wyatt)

Another fixture at the races is Shorty, who hails from Tasmania where he lives on a houseboat. He’s been riding ostriches since 1997, and is in agreement with Oliver in terms of technique. “Balance is the main thing,” he says. “You just gotta hang on.” He compares the experience of racing an ostrich to using a joystick on a video console, or maneuvering a helicopter. As he says, it’s all just “forward, back, left, right.” Shorty’s arms and hands bear the scars of numerous ostrich and camel accidents, but he’s still rugged enough to go by the nickname “Tasmanian Devil,” and loves to fly in to Nevada to compete in the races.

This year, the International Camel & Ostrich Races introduced zebra racing, too. (Photo: Rob Wyatt)

Watching the International Camel & Ostrich Races, one can’t help but wonder what its founder Bob Richards would think of it today. While writing an article in 1968, Richards died at his desk at just 57 years of age. An obituary describes him as a tireless newsman who also founded a yacht club in the desert, though it makes no mention of camel races. On a historical railroad car at the south end of Virginia City’s main thoroughfare, there’s also a memorial plaque for Richards describing him as “a touch of Twain revisiting the Comstock,” and in many ways, it’s true.

56th Annual International Camel & Ostrich Races (Photo: Rob Wyatt)

There are several similarities between Twain and Richards. They both worked at the Territorial Enterprise, exactly a hundred years apart, and each had a penchant for fabricating news stories. Twain himself wrote several articles that were hoaxes, including one about a petrified man and another about a massacre in which a destitute father scalped his wife and nine kids. Both Twain and Richards were also ardent promoters of Comstock Nevada, and Richards in particular sought to put the erstwhile mining boomtown of Virginia City, Nevada back on the map. With the International Camel & Ostrich Races, he did.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook