How a Traditional Punishment Ritual Made a Desert Town the Stabbing Capital of the World

The view of Alice Springs from Anzac Hill. (Photo: Lynda/flickr)

The view of Alice Springs from Anzac Hill. (Photo: Lynda/flickr)

In the last years of the 20th Century, Dr. Abraham Jacob, a newly arrived surgeon at the Alice Springs Hospital in Australia, noticed a recurring feature amongst his patients: they had all been stabbed. Almost every day someone would limp, crawl, or be carried into the emergency room with a stab wound. Dr. Jacob began keeping track of the admissions and found that over seven years Alice Springs Hospital admitted 1,550 stabbing victims, an astonishing number considering the population of Alice Springs is just 25,000. This works out at 390 stabbings per 100,000 population, by far the highest reported incidence of stab injuries in the world. (London, England, by comparison, has a stabbing ratio of just 47 per 100,000.) When Dr. Jacob announced his findings, Alice Springs was quickly dubbed the Stabbing Capital of the World.

Being a surgeon Dr. Jacobs knew plenty about cutting, yet the type of spiked and skewered patient he was treating surprised even him. As unusual as the volume of casualties was their gender—a near 50/50 male-female split. This was odd, noted Dr. Jacob, since stab victims whether in Sweden or Sydney are almost always young men. Yet perhaps the most bizarre feature of it all was the placement of the stab wounds. Only one percent of the wounds were found in the abdomen—the traditional place to stick someone—whereas fully 40 percent of the victims had been stabbed in the thigh. What on earth was going on?

The ‘springs’ that gave the town its name. (Photo: Searobin/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

To solve a mystery one must first study the scene of the crime. Alice Springs is Australia’s most famous outback town, situated amidst a vast area of desert and scrubland known as the “Red Centre” due to the color of its earth and rocks. It’s 620 miles to the nearest ocean and about 1,000 miles to the nearest major city. Metropolitan it is not. Nevertheless it acts as a tourist hub for visitors wishing to visit the giant sandstone monolith Uluru (also known as Ayers Rock) and those who wish to immerse themselves in Aboriginal culture.

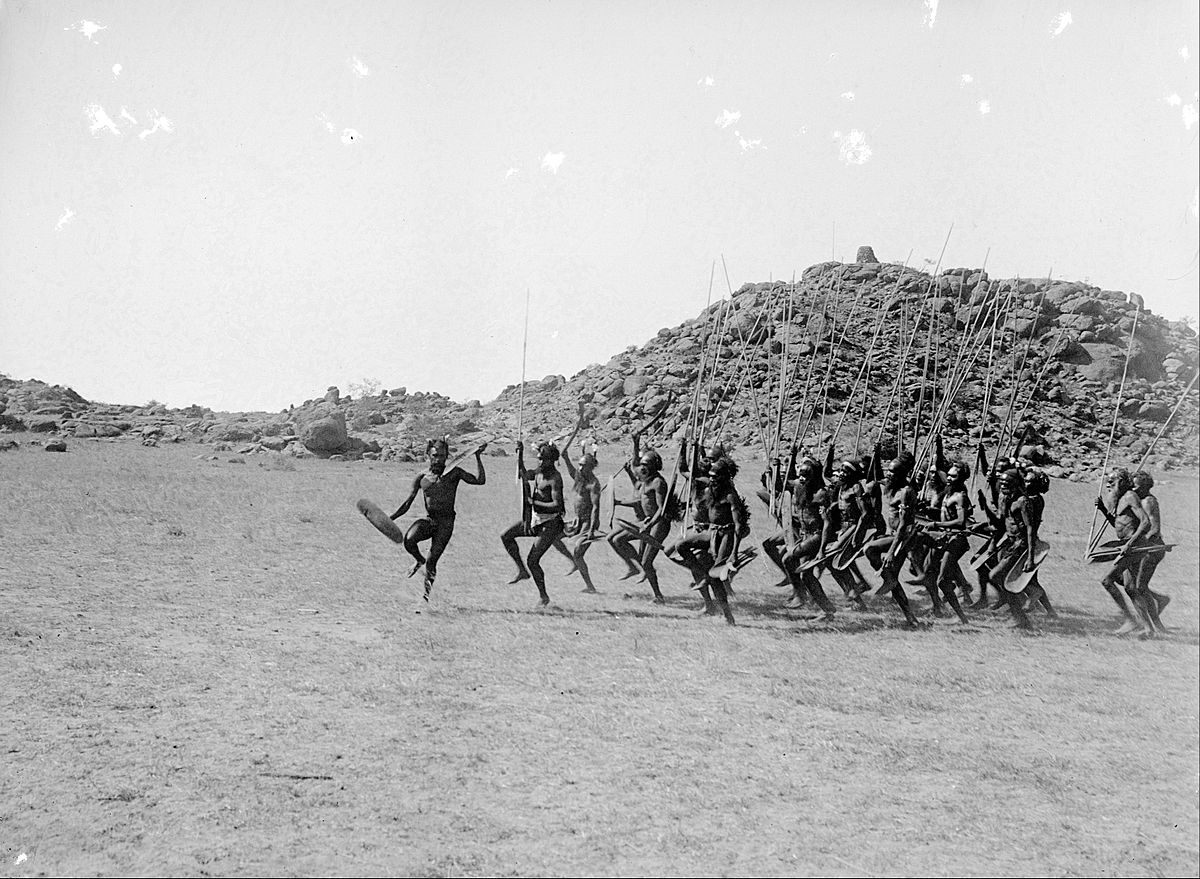

The Arrente people of Alice Springs giving a welcoming dance in 1901. (Photo: Walter Baldwin Spencer and Francis J Gillen)

Long before Alice Springs was settled by Europeans the area had been home to the Arrernte, Anmatyerre, Warrumungu and Warlpiri tribes for some 30,000 years, and Aboriginal people continue to inhabit the Alice Springs area in increasingly concentrated numbers. In the 1960s and 1970s a series of governmental attempts to integrate indigenous Australians with “whitefellas” saw many Aboriginal people migrate to the town from surrounding rural communities. They settled on its outskirts in rough and ready “town camps” and brought with them many of their cultural traditions. Most pertinent of these, at least to Dr. Jacob and the staff of Alice Springs Hospital, was the concept of “payback”. For of the 1550 stab victims Dr. Jacob counted during his seven years, 99.99 percent were Aboriginal.

Alice Springs airport. (Photo: DGriebeling/flickr)

Payback is a form of corporal, and sometimes capital, punishment administered by tribal elders to recalcitrant members of their tribe. This traditional punishment consists of the wrongdoer being stabbed in the thigh with a spear. The exact positioning of the wound depends on the crime. A stab in the lateral thigh punishes but does not cripple. A blow to the posterior thigh can permanently disable, while a spear applied to the medial thigh often punctures the femoral artery and kills. It is a violent yet delicate affair, and the elders wield their spears like scalpels.

Although it might seem like a form of vendetta, payback is a traditional form of conflict resolution, not escalation. It aims to restore peace to the community and act as a healing process and it is treated with the utmost seriousness by the felonious and the faithful alike. Such are the ties Aboriginal people have to their community that if an Aboriginal man is arrested for a crime by the Australian police he will often bail himself out in order to return home and receive payback. If he does not accept it his family will be ostracized and he will never be allowed to return home again.

A woomera (at left) is a spear-throwing device. Boomerangs are also used in payback. (Photo: Fir0002/Flagstaffotos)

Payback is by no means easy. In 1998, in Western Australia, a 19-year-old Aboriginal male was accused of murdering his 14-year-old girlfriend after sniffing petrol for hours. Before he turned himself in to the Australian police he agreed to suffer payback. This took place on an Australian Rules Football playing field where the 19-year-old waited without protest for the punishment to begin. He was speared in the upper thigh by the deceased victim’s father, her uncle, her brother and then by each of his own brothers. After this he was beaten with nulla nullas by other members of the community until he was knocked unconscious. A police officer who witnessed the punishment, but was powerless to stop it, noted that the payback took place “in an orderly fashion with each person only being allowed to strike him twice.” He was then delivered to prison.

Beatings often take place within the payback rite. The criminal is assailed with fists or even boomerangs and is occasionally afforded a small shield with which to protect himself or herself. But what is unchangeable in every payback ritual is the thigh-spearing.

The Australian government disapproves of such punishments, and seeks to replace them with court-mandated mediation. Some Aboriginal tribes now carry out a symbolic piercing of the thigh with a blunted spear in exchange for financial recompense. However some Australian judges have taken payback into account when sentencing Aboriginal criminals due to the sincerity with which they approach their punishment. And as the sheer number of stabbed people flooding into Alice Springs Hospital shows, the old ways show no signs of dying out.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook