How Ferris Wheels Escaped the Fair And Became High-End Urban Attractions

The Pacific Wheel in Santa Monica. (Photo: Gaston Hinostroza/Flickr)

The Pacific Wheel in Santa Monica. (Photo: Gaston Hinostroza/Flickr)

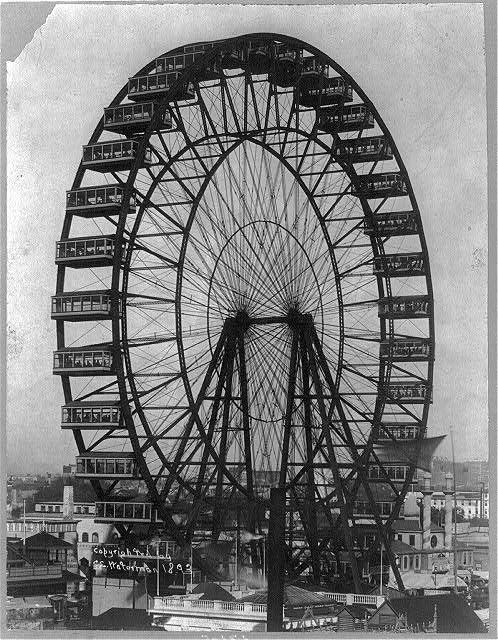

The Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 captured the imagination of the country; a city within a city was constructed to contain the event, complete with a massive reflecting pool. Visitors were dazzled by electricity, and by exhibits sent from around the world, including a replica Viking ship that sailed from Norway. Fairgoers could take in musical performances and art exhibitions and then recharge with a dizzying choice of libations and food.

Towering above it all a ride intended to provide guests with a bird’s eye view of the proceedings: the Ferris Wheel.

Designed by engineer George Washington Gale Ferris, Jr., the ride carried guests 250 feet into the air on 36 rotating cars. It opened to the public on June 21, 1893, and according to a New York Times story published the following day, over 5,000 visitors waited “patiently” to take their turn on the “great circle of steel and iron”. “Nobody was afraid to get on board the thirty-six cars” but “some of the women, and men too, experience a disagreeable sensation in the motion of the wheel”. That sensation aside, at one point the wheel is estimated to have sold around 150,000 tickets a week and was so popular that fans once rioted upon hearing they would be denied entrance.

It’s hard to imagine a shuttered Ferris wheel sparking a riot these days. Although Ferris wheels have become a staple at summer fairs, the advancement of thrilling roller coasters and other, flashier amusement park attractions, typically overshadow the nostalgic machines.

Not that people haven’t reinvented them in spectacular and unusual ways, and not that they don’t still have devoted fans.

The view from London Eye. (Photo: Lauren Tucker/Flickr)

The view from London Eye. (Photo: Lauren Tucker/Flickr)

Like Nick Weisenberger. He’s the founder of the website Observation Wheel Directory, a website devoted to all things Ferris wheel, and author of the book, Observation Wheels: Guide to the World’s Largest Ferris Wheels. Weisenberger is a mechanical engineer and also a serious roller coaster enthusiast. (He also writes for a roller coaster site, written four books on coaster design, and estimates that he’s ridden about 160 roller coasters around the United States and Canada.)

He started the site because he saw a need for it—there wasn’t an online clearinghouse for Ferris wheel information. Weisenberger writes about Ferris wheel physics, technology and history. He maintains lists of manufacturers, books, and even Ferris wheel accidents. Fellow enthusiasts send him tips, photos and corrections. But Weisenberger’s main obsession is “observation wheels”; inventions that he defines as typically 400-feet-high or larger in diameter. These massive creations would dwarf the wheel that astounded visitors to the 1893 fair.

For a long time, Weisenberger says, Ferris wheels maintained the status quo. Then came the London Eye. At 443 feet, it was the tallest wheel in the world when it opened to the public in 2000. Located on the South Bank of the Thames, the wheel offers riders a staggering view of London from 32 enclosed capsules that can hold up to 25 passengers each. General admission tickets are $30. But guests willing to pay (a lot) more can book cocktail excursions and private capsules, among other offerings, including dinner for eight for $7,805. Lavish extras are nice, but there are other, simpler factors that make a wheel successful.

“Location is number one,” says Weisenberger. “You want to be somewhere where there’s already going to be a lot of foot traffic. Most people aren’t going to make a special trip just to go on a big Ferris wheel.”

Ferris wheel at the Chicago World’s Fair, 1893. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Ferris wheel at the Chicago World’s Fair, 1893. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Once the London Eye after was built, says Weisenberger, the race was on. Cities swiftly undertook to outdo London and succeeded. The 520-foot Star of Nanchang was erected in 2006. The Singapore Flyer, which opened in 2008, unseated both by climbing to 541 feet. The Flyer was subsequently trumped by the High Roller in Las Vegas, by just nine feet, in 2014. The High Roller maintains its distinction as the world’s highest Ferris wheel; but there are other impressive wheels around the world. In addition to the Star of Nanchang, China also boasts the 394-foot-tall Suzhou Ferris Wheel and the Tianjin Eye (also 394-feet) which towers over a bridge. And plans to unseat the High Roller are afoot: construction has begun on the 630-foot New York Wheel in Staten Island and a 689-foot wheel in Dubai.

And, following the London Eye’s lead, these attractions offer their guests more than just a great view. The High Roller offers wedding packages and a happy hour. Visitors to the Singapore Flyer can buy a four-course meal and the services of a butler.

The Tianjin Eye, constructed over the Hai River in Tianjin, China. (Photo: David Hulme/Flickr)

The Tianjin Eye, constructed over the Hai River in Tianjin, China. (Photo: David Hulme/Flickr)

But size isn’t the only thing Ferris wheels designers have brought to the table in an effort to make their creations distinct. There are “centerless” or “hubless” wheels, which forgo the usual spokes that radiate out from the center of a Ferris wheel. The Big O, a centerless Ferris wheel in Tokyo, features a roller coaster running through the center. “Eccentric” Ferris wheels incorporate bowl-shaped tracks inside the wheel that allow some of the gondolas to race along the path, adding a bit of the speed and fright of a roller coaster. Mickey’s Fun Wheel at Disneyland is an eccentric wheel. The Uniroyal Tire Company constructed a Ferris wheel around the shape of a giant rubber car tire for the 1964/1965 New York World’s Fair. The tire (sans Ferris wheel elements) now sits beside the I-94 in Allen Park, Michigan. According to Uniroyal, at 80 feet high and 12 tons, it remains the “largest tire model ever built”. A casino in Macau is being constructed around what is being billed as the world’s first “figure eight” Ferris wheel, but Weisenberger is unconvinced.

The Big-O centerless ferris wheel in Tokyo. (Photo: Coby/Flickr)

The Big-O centerless ferris wheel in Tokyo. (Photo: Coby/Flickr)

“I’m not sure you could technically call it a Ferris wheel,” he says, “Because it looks more like a track that cars follow. It doesn’t rotate like a typical Ferris wheel, but they’re trying to claim it as one.”

Weisenberger predicts that the future of lavish wheels lies in interactivity. Representatives of the New York Wheel want to make sure that their ride is compatible with cameras and tablets so riders can easily share their experience over social media, and the designers of Japan’s proposed Nippon Moon Ferris wheel want to incorporate an app that allows visitors to “switch from reality to digitally altered views from the capsules”.

But the vast majority of Ferris wheels do not offer champagne toasts and augmented reality, and as such, they often take a backseat to noisier fair ground and amusement park offerings. Even Weisenberger says that if he’s at a carnival, he’ll often skip the dinkier wheels. His favorite amusement park ride is far afield from a leisurely turn on the wheel—he loves The Voyage at Holiday World in Santa Claus, Indiana. A wooden coaster that offers 24.3 seconds of zero gravity and steep drops, Weisenberger says that it’s a “crazy” ride that is almost too long.

Diamond and Flower Ferris Wheel in Tokyo. (Photo: kobakou/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

Diamond and Flower Ferris Wheel in Tokyo. (Photo: kobakou/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

So with all the glitzier offerings, why do Ferris wheels remain fair and theme park perennials?

For starters, brand recognition. “Ferris wheels have been around for over a hundred years and they’ve kept the same basic shape—everyone knows one when they see it,” Weisenberger wrote in an email to Atlas Obscura. Usually a sedate ride, Ferris wheels are perfect for families.

“There’s also the romantic angle,” continues Weisenberger. “Getting stopped at the very top while riding with your significant other is a special moment no doubt resulting in thousands of marriage proposals made on wheels.” He even occasionally gets emails from people who mistake his site for a wheel’s official site, asking him to stop the wheel at the top so they can pop the question.

Atop the Singapore Flyer. (Photo: Cheryl/Flickr)

Atop the Singapore Flyer. (Photo: Cheryl/Flickr)

And, of course, there is the same thing that attracted the amazed visitors of the Chicago World’s Fair and connects those people from the past to us.

“People generally like to be scared in a safe environment; we crave experiences that seem risky but really aren’t,” writes Weisenberger. “It seems humans have always been attracted to climbing to high places in order to view our world from above.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook