How Flap Illustrations Helped Reveal the Body’s Inner Secrets

Sixteenth century scholars peeled away anatomical ignorance one layer at a time.

For much of recorded history the human body was a black box—a highly capable yet mysterious assemblage of organs, muscles and bones. Even Hippocrates, a man who declared anatomy to be the foundation of medicine, had some interesting ideas about our insides.

By the early Renaissance, scientists and artists were chipping away at this anatomical inscrutability, and illustration was proving a particularly effective way to spread what was being learned via human dissection. There remained one nagging issue, however: accurately representing the body’s three-dimensional structure on a flat, two-dimensional piece of paper. Some artists relied on creative uses of perspective to solve the problem. Others began using flaps.

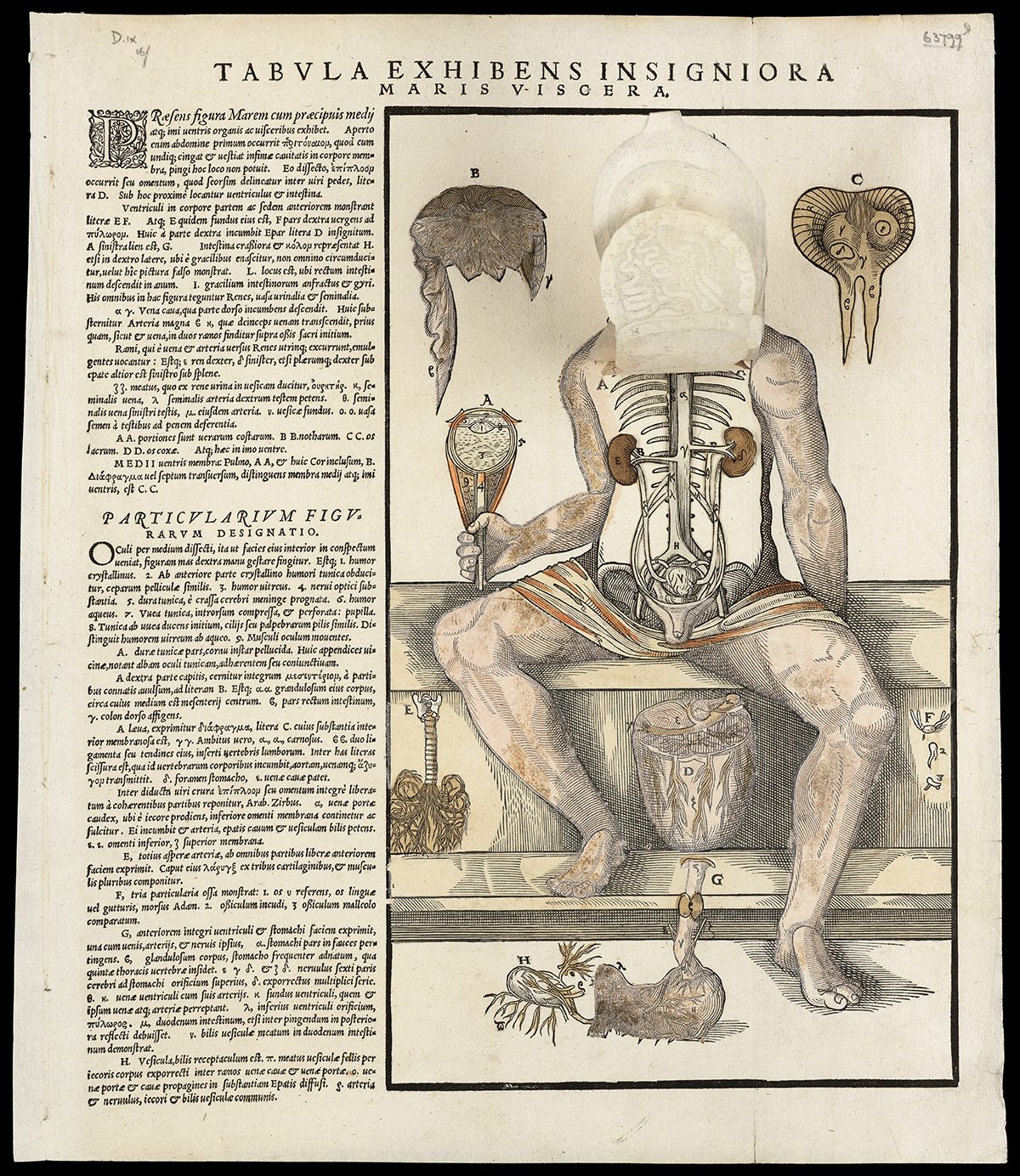

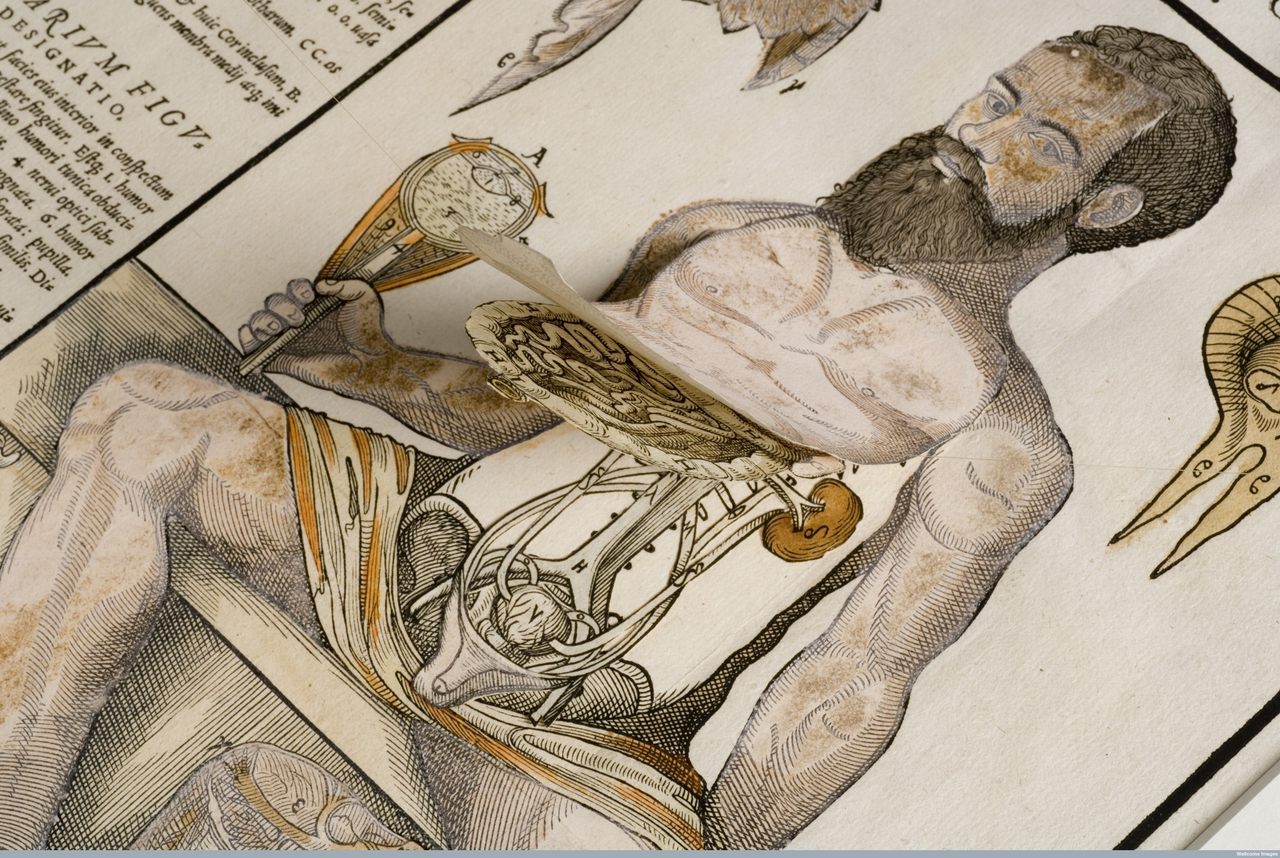

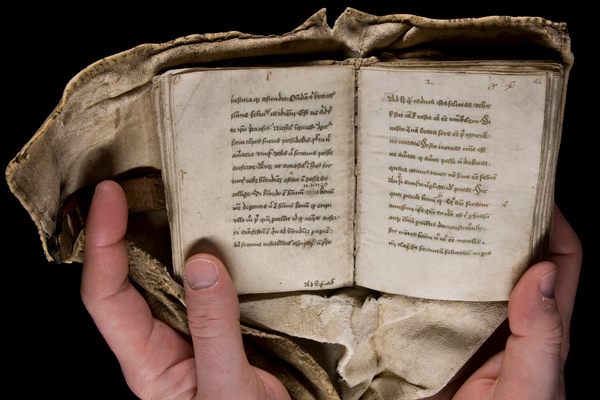

The first known anatomical flap prints were produced in Strasbourg, France, in 1538 by Heinrich Vogtherr. The German artist, printer, and poet pieced together multiple layers of pressed linen so that readers could open up his illustrations to reveal the positions of major organs in both male and female figures. While volvelles, or multi-layered, moveable wheel charts, had been used in medieval astronomy and navigational texts, this was the first time a similar idea had been applied to anatomical illustration.

As it turned out, people were eager to learn about their insides, and early flap anatomies (or “fugitive sheets” as they’re now known) proved immensely popular during the 16th century. Many of the loose-leaf prints came with descriptions of individual organs and were ultimately reprinted in a variety of languages. Some were even meant to be paired with separate texts that offered further insights into the body and how to treat various maladies.

“These were very much part of a bigger idea of not only understanding anatomy, but also having a sort of folk remedy available,” says Cali Buckley, an art history PhD candidate at Penn State who has studied flap anatomies. “It was very much about public edification.”

Still, despite such instructive aims, not all early flap anatomies got everything right. Flip through one of Vogtherr’s female illustrations, for example, and you’ll find a U-shaped curiosity called the “lacmamil.” “It’s basically two tubules coming down from the nipples that were thought to turn blood into milk, which is something that obviously does not exist,” Buckley says.

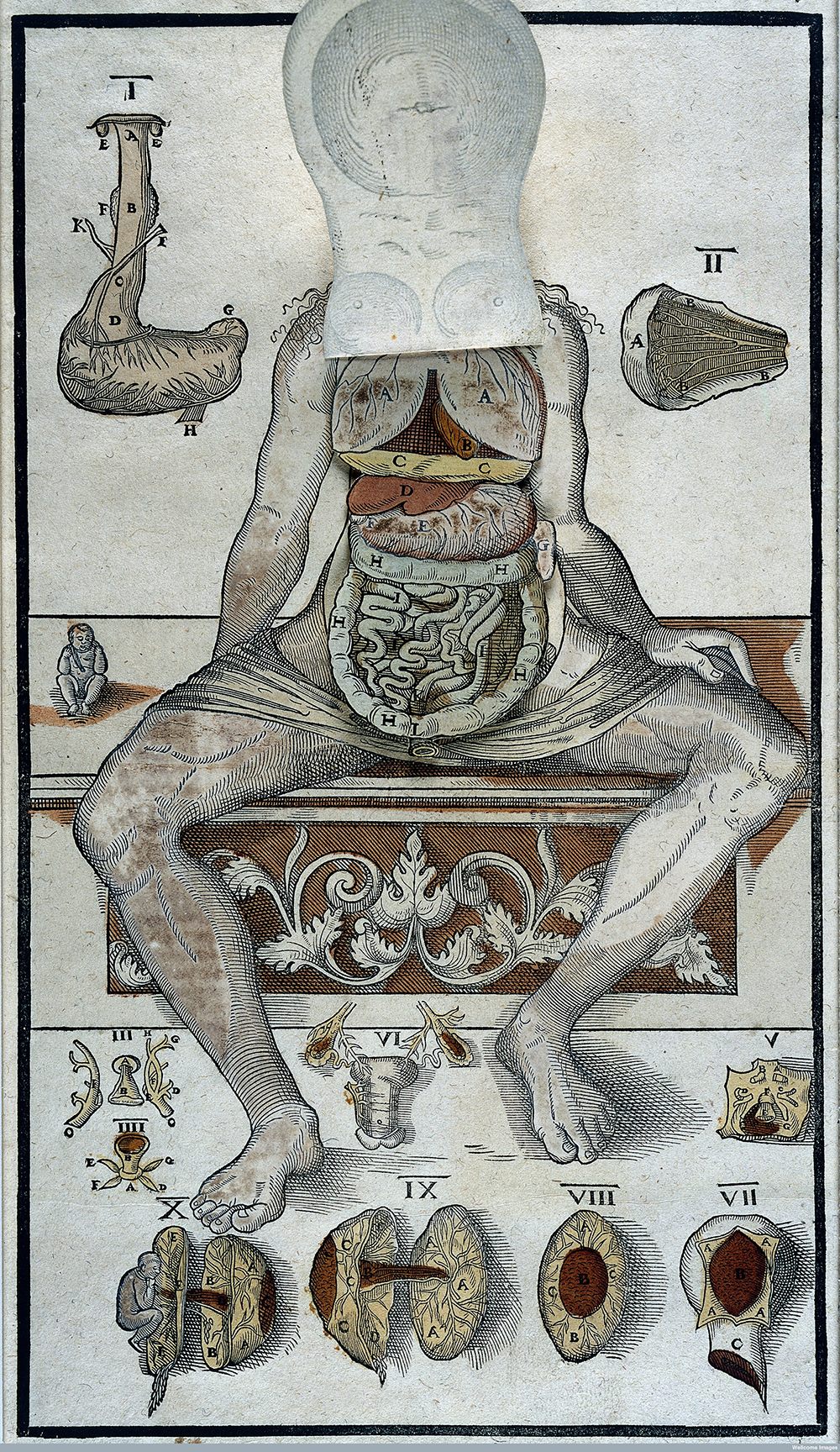

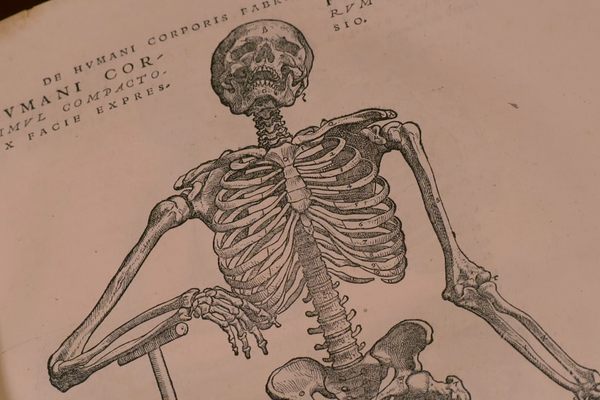

While early flap anatomies were aimed at a general public interested in the body’s inner workings, it didn’t take long for more specialized audiences to emerge. Andreas Vesalius, the Dutchman responsible for two of history’s most celebrated anatomical texts, almost certainly knew about flap anatomies when he published his 1543 twin opuses, De Humani Corporis Fabrica (“On the fabric of the human body”) and its condensed, much less expensive companion, Epitome. These were both aimed squarely at students of anatomy, with the latter being an attempt at “compressing all the parts of the human body into a few pages of text and pictures,” according to the National Library of Medicine’s book, “Hidden Treasure.”

To that end, students were invited to cut out various anatomical parts from a spare page in Epitome and paste everything together to form their own personal flap anatomy. Vesalius’ theory was that this would help them memorize and better understand both the composition and spatial arrangement of the body’s internal organs, nerves and muscles.

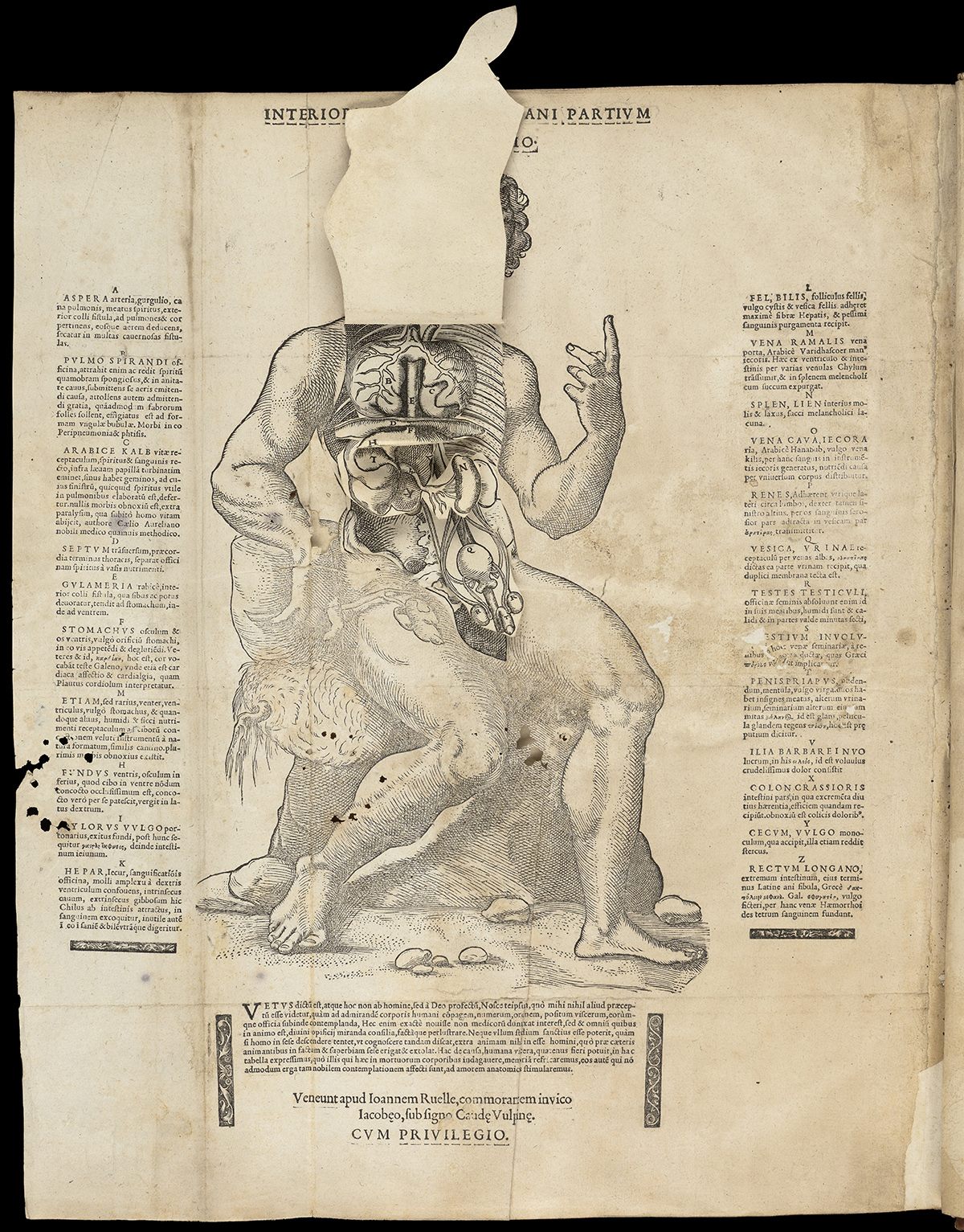

If Vesalius helped establish a new benchmark for anatomical rigor in flap anatomies, later practitioners like Johann Remmelin combined that precision with artistic flair. His 1619 Catoptrum Microcosmicum features three full-page plates with dozens of detailed anatomical illustrations of both male and female bodies. “They were incredibly complicated, but also accurate and kind of wildly pretentious,” says Buckley. Catoptrum Microcosmicum features text in Greek, Latin and Hebrew, and mixes together ideas from literature, poetry and philosophy. It was also “vaguely alchemical,” according to Buckley, insofar as it tried to give readers an understanding of the entire universe, using the body as a microcosm.

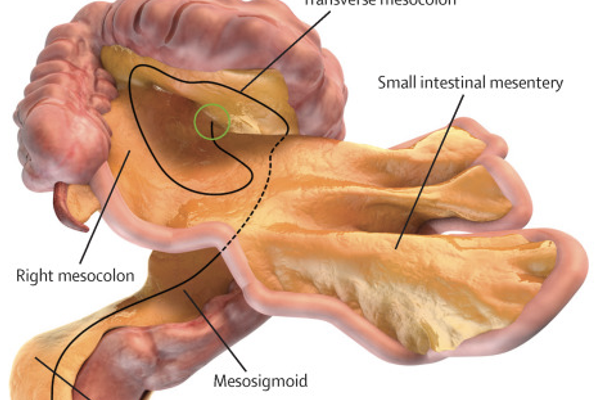

As printing techniques grew more sophisticated in the 18th and 19th centuries, so too did flap illustrations. Gustave J. Witkowski’s colorful “Human anatomy and physiology” has a multi-layered brain with more than 20 movable parts. Similarly, Eduard Oskar Schmidt’s “The anatomy of the human head and neck” features a mustachioed Victorian man, whose head you can peel back to reveal the underlying musculature, nerves, eyes and brain.

Pregnancy, which had always been a preoccupation for male anatomists and physicians, also got the flap treatment. George Spratt’s epically titled 1848 edition of “Obstetric Tables: Comprising Graphic Illustrations with Descriptions and Practical Remarks; Exhibiting on Dissected Plates Many Important Subjects in Midwifery” shows, among other things, the various stages of pregnancy. The preface to Spratt’s American edition raved:

The superiority of the present work over any other series of Obstetrical illustrations, is universally admitted. It is a happy combination of the Picture and the Model…To the busy practitioner, who wants something to refresh his memory, it obviates the necessity for continual post mortem examination…To the student it is equivalent to a whole series of practical demonstrations, with the advantage that it can be carried about with him and studied wherever he may desire.

Eventually, ever larger flap contributions appeared, like “White’s Physiological Manikin” in 1886. Produced by James T. White and Co. and “examined and approved by Frank H. Hamilton M.D.,” one of the four physicians who tried to save President Garfield, this wall-friendly model was meant for classrooms and doctor’s offices. Among other things, it showcased “the form, position, color, and relation of the organs of a healthy body,” according to “Hidden Treasure.” It also had some morally instructive flaps that depicted “the effects of alcohol and narcotics on the human stomach, and the deformation of the female rib cage caused by corsetry.”

Today, X-ray imaging, sonograms, CT scans, and MRIs let us peek inside the body in ways 16th century anatomists couldn’t have dreamed of. But it’s worth noting that even with all these technological advances, flap anatomies never really went away. Popular pop-up books like Jonathan Miller’s “The Human Body” are in many ways the modern descendants of flap anatomies. And if you ask a medical or nursing student about their own experiences learning anatomy, you’ll likely hear just as much about layered plastic anatomical transparencies as you will about layered computer animations. Turns out, Vesalius was onto something.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook