During an Annular Eclipse, Look to the Shadows

While some people in the Western Hemisphere will witness a “ring of fire” during the eclipse, many more will experience the phenomenon of crescent sunlight.

Atlas Obscura’s Wondersky columnist Rebecca Boyle is an award-winning science journalist and author of the upcoming Our Moon: How Earth’s Celestial Companion Transformed the Planet, Guided Evolution, and Made Us Who We Are (January 2024, Random House). She regularly shares the stories and secrets of our wondrous night sky.

The ancient Chinese Shu Ching, or Book of Documents, includes what may be the oldest written account of a solar eclipse. It records that, on Oct. 22, 2134 BC, “the Sun and Moon did not meet harmoniously.” People believed that during an eclipse, the Sun was being devoured by a heavenly dragon; in fact, the word for “eclipse” was the same as the word for “to eat.” In China at the time, as in Babylon 1,500 years later, people would bang a drum and shout in an attempt to ward off the dragon.

Though banging drums is a lovely custom, I prefer to imagine what is actually, physically taking place, which to me is as awesome as any myth.

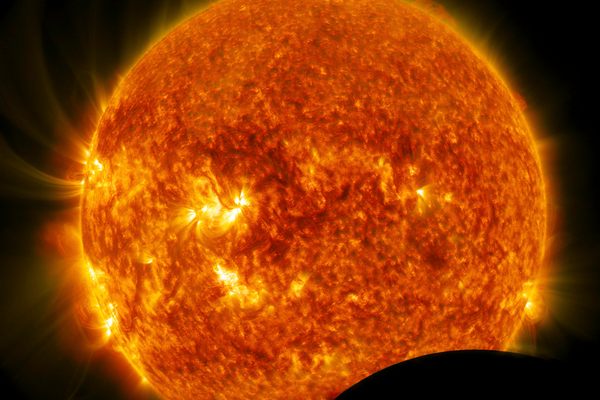

This Saturday, for some people in the Western Hemisphere, the Sun will disappear for a few minutes and appear to leave a flaming hole in the sky. Instead of a ball of fire, the Sun will transform into a ring of fire, a strange and wondrous sight. This is an annular solar eclipse, and it happens because the Moon is right smack in front of the Sun.

A solar eclipse only happens during new Moon phases, when we otherwise wouldn’t be able to see our nearest celestial companion. Though we get a new Moon every month, we do not get solar eclipses as often because of our satellite’s oddball path around the planet. Sometimes the Moon casts a shadow just above Earth, and sometimes just below. This weekend, the Moon’s shadow will fall onto Earth, just right for people in parts of the Western Hemisphere to see it.

The annular eclipse is a preview of a more incredible, rarer event next April, when a total solar eclipse will cross the continental United States. There is no experience on Earth like a total eclipse; make plans to see it, if you can. But this weekend’s “ring of fire” eclipse is an event you should try to see first (safely, with eclipse glasses), if you can get yourself into the western U.S. or parts of Central and South America. Here’s a map showing the eclipse path; if you can’t travel to see it in person, you can watch the eclipse online.

Eclipses happen because the Sun and Moon appear to be roughly the same diameter. The Sun is actually about 400 times larger than the Moon, but it is also about 400 times more distant, so they seem like the same size in our sky.

The Moon’s distance to Earth changes regularly during its elliptical orbit. When it is closest to us, and when it is full during this phase, we experience a supermoon. When it is more distant, the Moon’s apparent size is just a tad smaller, not quite big enough to block the entire Sun. These varying distances are why we have an annular eclipse this weekend, and a total eclipse in April 2024.

The Moon was closer to Earth in the distant past, hundreds of millions of years ago. It’s been spiraling away from us ever since, and at some point in Earth’s distant future, total solar eclipses will not occur. The Moon will simply appear too small. But right now, at this infinitesimally brief moment in the history of life on Earth, let alone the history of the solar system, we can watch the rare and fearsome sight of our home star vanish behind the Moon.

The distances among the Sun, Earth and Moon are a cosmic coincidence that I sometimes find hard to believe. Why isn’t the Sun 400 times bigger, but 300 times more distant? Why isn’t the Moon a little bit smaller, or a little bit bigger? Why isn’t this ratio literally anything else at all? Similar questions include, why here? Why us? Why nowhere else? The best answer is to just enjoy the spectacle, brought to you by shadows.

The Moon’s shadow forms two concentric cones, composed of an inner shadow called the umbra, where the sun is completely obscured, and an outer, broader cone called a penumbra, where sunlight still shines but it is partially blocked. The umbra can be seen in a narrow geographic ribbon across the Americas, and it’s where you will see a full eclipse; under the penumbra, which covers much of the western U.S., Central and South America, you will see a partial eclipse.

Like the gears of a clock, a combination of precise positions and movements initiate an eclipse of the Sun. As Earth spins, day breaks. The Sun and Moon appear to trace a path across the sky. The Sun is not moving (at least not perceptibly); Earth’s rotation makes the star’s position change. The Moon is moving around us while the Earth rotates, so it seems to move too, but it appears to go slower than our star. The partial solar eclipse begins as the Sun catches up to the Moon’s position in our sky. On Saturday morning around 8:06 a.m. Pacific time, people in Eugene, Oregon, will be the first to see the Moon appear to take a bite out of the Sun. The bite will get progressively bigger until the full annular eclipse begins at 9:16 a.m. Pacific time.

The annular eclipse only lasts about four minutes (depending on your precise location under the Moon’s shadow) but the partial eclipse, which will be visible over a much wider geographic area, lasts about an hour and 15 minutes before and afterward. During this phase, shadows cast by objects on Earth will change in unusual ways. One lovely place to be during a partial solar eclipse is underneath a tree, if you can find an evergreen or a deciduous tree that has not dropped its leaves yet. Look at the ground. In the dappled light, you will see crescents everywhere: the crescent Sun.

Sunlight is the heavens reaching down to touch us right where we stand; I think about this when I step into the light. But crescent sunlight is the Moon joining this experience. Its darkness, rather than its light, reaches out to touch us, too.

You are connected to both the Moon and the Sun, just as you are connected to both the light and the dark, and a solar eclipse is physical evidence. You might even find yourself compelled to shout out, or to beat a drum.

Is there something you’d like to know about our brilliant night sky? Share your stargazing questions with us and you may see them answered in a future Wondersky column!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook