I Found a Female Serial Killer in My Family Tree

The church in the village of Guestling, where Luke Spencer’s ancestor lived. (Photo: Mark Duncan/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.0)

The church in the village of Guestling, where Luke Spencer’s ancestor lived. (Photo: Mark Duncan/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.0)

Thanks to online genealogy services, tracing your family tree has never been easier. Which means it has also never been easier to discover skeletons hidden in the family closet—obscure distant relatives; long-held secrets. Or a mass murderer.

Exploring my family tree, I discovered among my forebears a genuine serial killer on my mother’s side of the family. It was a chilling discovery, but what was all the more extraordinary was that the murderer was, in fact, a murderess.

The plotting of my family tree suddenly became an exploration of old London court papers, lurid eye witness accounts, midnight exhumations, entries on Murderpedia.org, and macabre reports from the archives of the London Times. All of this centered around a seemingly normal Victorian housewife, who coolly dispatched her loved ones with arsenic, until she was at last caught and hanged in the town square.

The small, peaceful village of Guestling, population just over 1,000, lies in the picturesque rolling hills of the county of Sussex on the southern coast of England. It is roughly three miles northeast of Hastings, where King Harold received a French arrow in his eye en route to losing his kingdom in 1066 to the Norman conquest.

Mary Ann Geering, who would eventually become known in newspaper reports as the Guestling Murderess and the Murdering Mother, was born in 1800 to a family of agricultural laborers. Like many girls of the lower classes, at the age of 18, she became a maid at a larger house. It was here she met Richard Geering, a farm worker from East Sussex. They were duly married and went on to have eight children.

In September of 1848, Richard suddenly took ill. He complained of chills and a pain in the abdomen, sweated profusely, and was having difficulty breathing. The local physician, a Dr. John Lucas Pocock, was called and diagnosed an intermittent fever. The London Times reported that, calling back two days later, Pocock recalled seeing Geering’s wife, “who informed me that her husband was dead, that he died about a couple of hours before I was called. I expressed my surprise.”

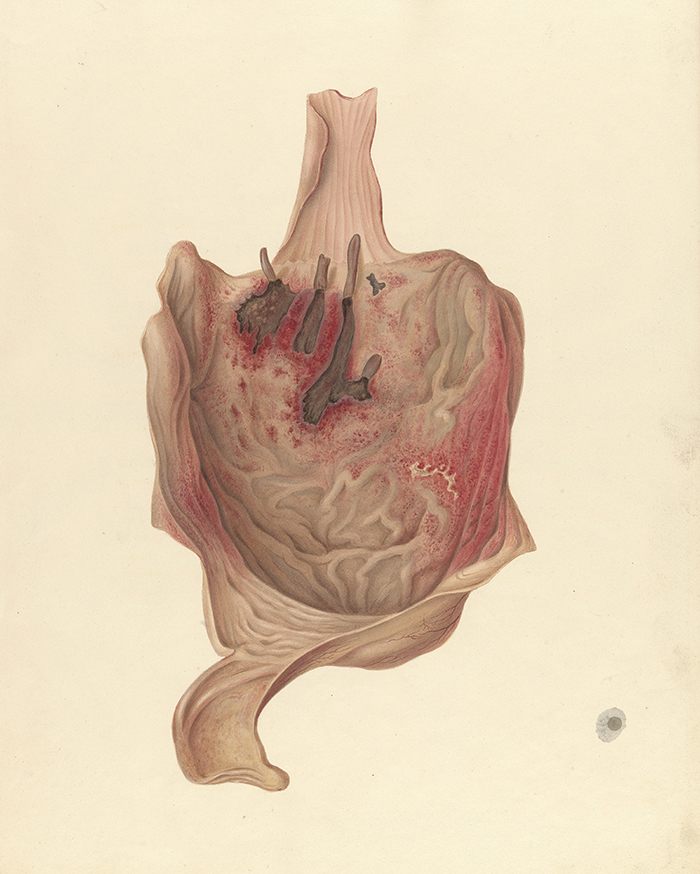

An 1833 illustration of the effects of arsenic poisoning on the stomach. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London)

An 1833 illustration of the effects of arsenic poisoning on the stomach. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London)

One Sunday in January 1849, one of the Geerings’ middle sons, George, then aged 21, started to suffer from similarly violent bouts of sickness and a raging thirst. He complained to Dr. Pocock of “having heat on his inside.” George died three days later. Six weeks after his funeral, his older brother James, 26, also fell ill, passing away on March 6th, 1849. Three weeks after that, a third brother, Benjamin aged 18, began to suffer from an unnatural hunger and vomiting.

Dr. Pocock’s suspicions were aroused by the recurring symptoms and deaths taking place at the modest Geering cottage in Guestling. A second physician by the name of Ticehurst was called in, Benjamin’s diet was altered, and he soon began to recover.

Because the doctors were already fairly certain that Benjamin was slowly being poisoned by his mother, he was removed from her care. They also suspected that the other deaths, attributed at the time to natural causes, were anything but.

The only way to tell was to exhume the bodies.

Despite its reputation as the one of the more respectable newspapers of the era, the London Times was not above lurid prose when it came to reporting crime stories in Victorian England. Under the headline “The Poisonings in Sussex,” on April 30th, 1849, the Times published an account of the exhumations:

“The three graves from which the bodies had been taken were on the east side of the church, and were very watery. The coffin containing the body of Richard Geering was first brought out of the church and placed on a tombstone. The lid was then unscrewed, and on its removal the body was found to be in an advanced state of decomposition, except in the region of the abdomen.”

Reading like a chapter from the work of Edgar Allan Poe, the Times continued:

“The effluvium was dreadful, and the body swimming in water. To remove the latter holes were bored in the coffin. The whole of the deceased’s intestines were removed and placed in jars. The coffins containing the bodies of the two sons were then brought out and opened.”

The investigation showed that the stomachs of the deceased were all in an unusually good state of preservation, while the rest of the bodies had decayed. Small pieces of a “white, gritty matter … resembling arsenic” were found.

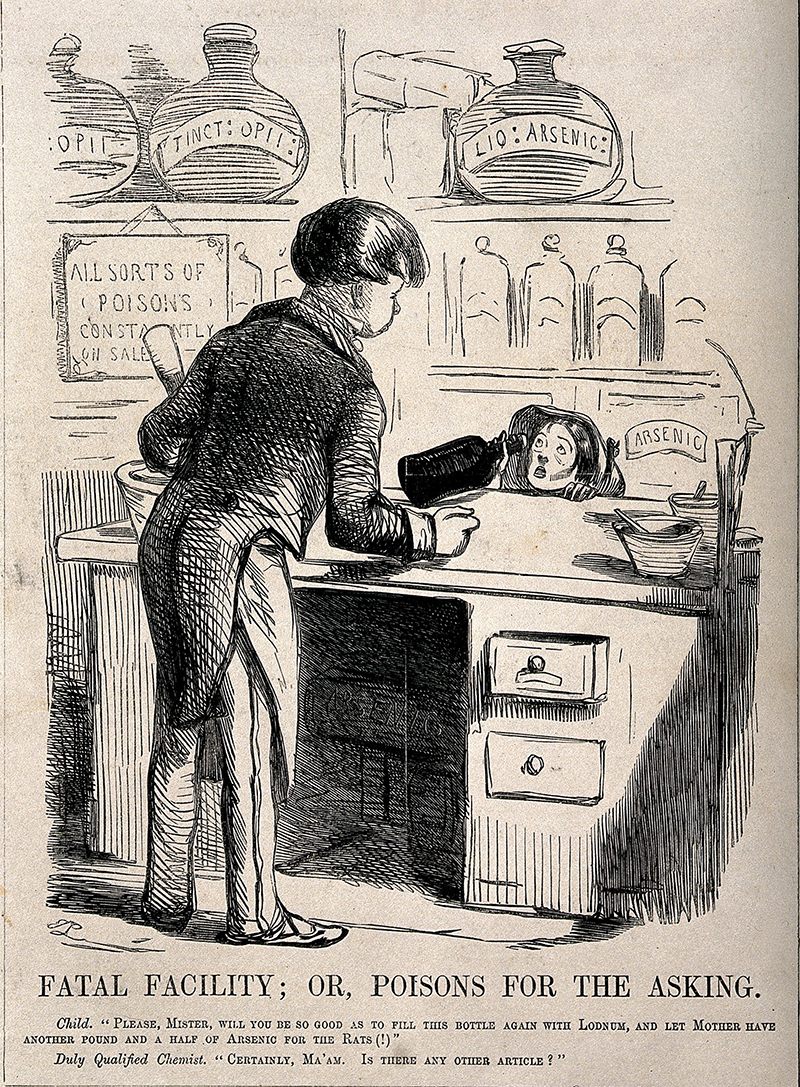

An illustration from the 1840s showing the ease with which poisonous substances were available. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London)

An illustration from the 1840s showing the ease with which poisonous substances were available. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London)

The investigation concluded that “on the whole, the appearances presented by the different bodies seemed to be strongly indicative of death by poison. Arsenic has been discovered in sufficient quantities to account for death.”

Mary Ann Geering was immediately placed under arrest to await trial, while the jars were sent to London for forensic examination. The remaining Geering children were sent that most Victorian of institutions: the poor house.

An inexpensive by-product of the enormous mining industry, arsenic was a common ingredient in items developed during the Industrial Revolution. In his book, The Arsenic Century, James C. Wharton says it was found in “candies to candles to cookware, concert tickets, and preserved partridge heads used to ornament ladies headdresses.” It was used in bright dyes, such as the fashionable Paris Green, which, says Wharton, colored “playing cards, wallpaper, clothing and ribbons.” Ladies would mix arsenic with vinegar and chalk, and rub the mixture on their faces and arms to make themselves paler, to show that they did not work in the fields. Arsenic and old lace was indeed the order of the day.

It was also widely available to Victorian households as a deadly rat poison.

On August 5th, 1849, the trial of my arsenic-poisoning ancestor began. The next day, the London Patriot newspaper reported, “Mary Ann Geering, a woman of masculine and forbidding appearance, aged forty-nine, was arraigned at Lewes Assizes for murder.”

The court heard from a Mr. Pittman, a chemist in Hasting, who remembered the accused as a regular customer, and of how she purchased arsenic on four occasions. “Two pennyworth,” he recalled, “rather a large quantity of poison to sell over the counter.” He also claimed that he would not have “sold such a quantity to a stranger.” But Mrs. Geering was a known customer, and she explained it was for dealing with rats.

An advertisement c. 1890 of arsenic-free wallpaper. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London)

An advertisement c. 1890 of arsenic-free wallpaper. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London)

The prosecution divulged that two years before his death, Richard Geering had inherited £20, which he had deposited in the Hastings Savings Bank. In the mid 19th century, that would equate to just under half a year’s salary for a laborer.

Most damning of all was the testimony of Mary Ann’s son Benjamin, who, recovered from his poisoning, gave evidence against his own mother. He explained how the family had been members of a Burial Friendly Society, an ad hoc insurance arrangement in the village, where subscribers would “in the case of illness receive ten shillings a week, and on death, one shilling from each member.”

As the gentry and farmers of Guestling crowded in the courtroom to hear the mounting evidence of financial gains, a local widow, Judith Veness, was called to the witness stand. “The deceased and his wife frequently disagreed,” she said, “and I have heard her to say to him several times, ‘I wish you were dead—you are only a trouble to me.’”

A witness from the Royal College of Surgeons gave medical evidence that the jars of intestines and viscera recovered during the exhumations indeed contained high amounts of arsenic.

Dressed all in black and wearing a shawl, Mary Ann Geering confessed to the murders and, as reported in the Times, “after an absence of 10 minutes, the jury found a verdict of guilty. Sentence of death was passed; which the prisoner heard almost unmoved.”

In Victorian England, the maximum penalty of the law was public execution: “the drop.”

The current FBI definition of a serial killer is a perpetrator who commits three or more murders with a distinctive “cooling off’ period between crimes. This differentiates from “spree” killers or mass murderers, who kill multiple people in a shorter amount of time. Female serial killers are rare, and often overlooked.

Marissa Harrison, Professor of Psychology at Penn State, made a study of all known U.S. serial killers dating back to the Revolutionary War. There are just 64 recorded female serial killers— roughly one in six of all known serial-killer cases. Quoted in the New Yorker, Harrison said “I think society is in denial that women are capable of such hideousness.”

Her study showed that while their male counterparts aggressively hunted strangers, female serial killers largely targeted people they knew—usually family members—and that their primary weapon was poison. Further, they were more likely “to kill for money or power.”

Mary Ann Cotton, another serial killer who is believed to have poisoned up to 20 people with arsenic. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Mary Ann Cotton, another serial killer who is believed to have poisoned up to 20 people with arsenic. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Harrison also told the New Yorker that “contrary to preconceived notions about women being incapable of these extremes, the women in our study poisoned, smothered, burned, choked, bludgeoned and shot newborns, children, elderly and ill people as well as healthy adults; most often those who knew and likely trusted them.”

These profiles certainly match the Guestling Murderess.

Mary Ann Geering was by no means the only such case of a female murderer in Victorian England. Between 1843 and 1890, another 48 so-called “Black Widows” were convicted and put to death. In her book Victorian Murderesses, Mary S. Hartman profiled how “these lower class murderesses … chose their victims largely among spouses, relatives and acquaintances.” A look at their motives reveals that “they murdered far more frequently for money.”

Of these 49 convicted killers, just under half did so “often for very small amounts, such as the pitiful sums obtainable from burial societies.” Burdened by crippling poverty and unable to care for their children, some of these mothers used an unthinkable alternative. More often than not, arsenic poisoning was the poison of choice.

“The symptoms of arsenic poisoning were vomiting and dehydration,” David Wilson, a professor of criminology at Birmingham University, wrote in the Daily Mail. A doctor in the 19th century, when life expectancy was considerably shorter than today, “was always more likely to diagnose this cluster of symptoms as gastroenteritis, especially in patients who were poor and undernourished, than to suspect murder.”

The key to a successful arsenic poisoning was patience. Too many grains and a quick violent death would alert the attending physician. It seems likely, given the subtle nature of arsenic poisoning, that many more “Black Widows” eluded suspicion and arrest.

Mary Ann Geering was unable to escape detection, convicted largely on the evidence of the son she had tried to poison. On August 21, 1849, the Guestling Murderess was hanged in Lewes town square.

The Sussex town of Lewes, where Mary Ann Geering was hanged for her crimes. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The Sussex town of Lewes, where Mary Ann Geering was hanged for her crimes. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

According to the Times, “between three and four thousand made their appearance” to watch her hang. “No feeling was manifested when she mounted the scaffold,” the Times said. “In about two minutes the necessary arrangements were completed and the wretched criminal ceased to exist.”

My ancestor was left to hang in the square for about an hour, until she was cut down and “buried in the precincts of the gaol at four o’clock.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook