In the 1900s, Being a ‘Cigarette Fiend’ Was a Legitimate Defense for Murder

Smoking kills.

A postcard from 1917 showing a “Cigarette Fiend”, in a spell from “Madame Nicotine”. (Photo: Public Domain)

At the dawn of the 20th century, the United States fell victim to an incredibly dangerous drug. Children were easy prey for the menace, one so toxic that even casual use turned the most mild-mannered man into a criminal maniac. “[T]he brain becomes sluggish … [a]t the same time the mind is full of wild fancies,” wrote Dr. Carlton Simon in the New York Journal. “[T]he actions are not guided by the will. Normal deeds vanish, and theft, murder and other horrible crimes result.”

What was this frightening Jekyll-and-Hyde drug? The “dope stick.” The “coffin tack.” The lowly cigarette.

You have to be kidding me, you’re probably thinking. My Uncle Ted smoked two packs a day for 30 years and he never hurt a fly. But cigarettes were still a novelty back in the early 1900s, with most still hand-rolled Turkish affairs; the vast majority of smokers chose cigars or chewing tobacco over the “paper pipe.” Philip Morris came to New York in 1902 and introduced Marlboros, manufactured (like all cigs of the time) from bits and bobs left over from producing other tobacco products. Nicotine was already established in medical research as a deadly poison, but exactly how it affected the human body was up for debate. (Some pioneers did voice a concern over “cigarette cough” and possible correlations to heart disease.)

One thing everyone seemed to agree on, however, was that it ruined the mind, creating the “cigarette fiend—a deplorable soul whose habit “sap[ped] the moral and mental life of its devotee.”

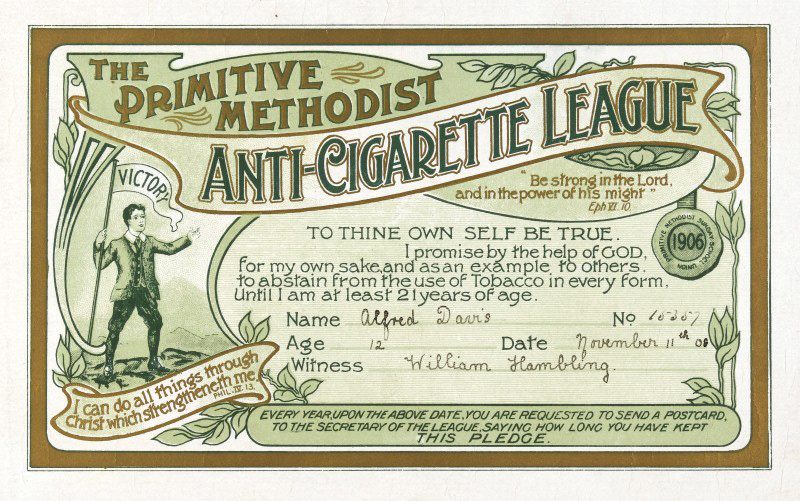

A signed pledge card from the Primitive Methodist Anti-Cigarette League, with a promise “to abstain from the use of tobacco in every form, until I am at least 21 years of age.” (Photo: Wellcome Images, London/CC BY 4.0)

The theory that regular cigarette smoking invariably turned the user homicidal was so widespread that it became a regular part of the insanity defense:

- 1899: George W. Schan fatally shoots his father twice in the head. Despite ongoing tension at home over an inheritance feud, friends claim “the excessive use of cigarettes unbalanced his mind.”

- 1900: John Garrabrant beats his 16-year-old schoolmate to death. Another boy, Casmer Teresnick, uses an ax to murder a local canal boat captain. They are arraigned on the same day as “cigarette fiends both, with the yellow stain of the poison on their bony hands …”

- 1901: Jim Harris shoots John Allen, a wealthy and eminent shopkeeper, in the doorway of his own home. Though “ugly rumors” persist about a relationship between Harris and Mrs. Allen—possibly branding her an accomplice—Harris’ defense was he “had been a cigarette fiend since he was two years old.” (Mrs. Allen was acquitted.)

- 1905: Martin Paulsgrove shows little concern or remorse after fatally shooting his girlfriend. This, of course, is due to his being “a confirmed cigarette fiend … [n]o doubt the defense will be insanity, caused by the excessive use of the deadly cigarette.”

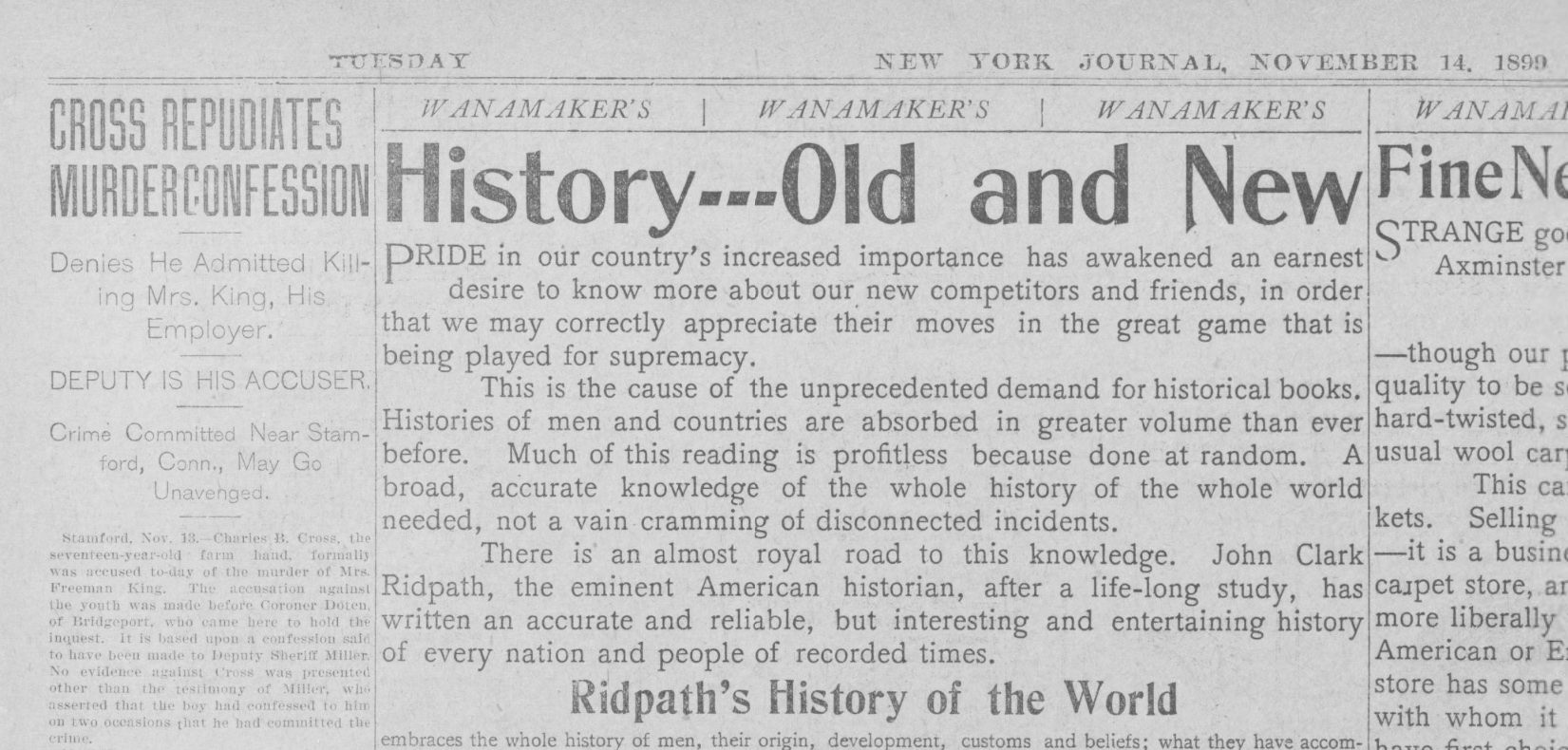

One of the most publicized “cigarette fiend” cases was that of 16-year-old Charles Cross. Sometime between the 7th and 9th of November, 1899, he brutally beat 60-year-old Sarah King to death. Cross lived with Mrs. King and her husband, Freeman, a printer who was frequently out of town for business. Mr. King hired the boy to do chores and generally help his wife around the house in his absence. After a brief period of denying he’d been involved, Cross finally confessed, stating an uncontrollable “desire to gratify his passions” caused him to attack the woman, smashing her head repeatedly against the floor when she resisted.

The New York Journal from November 14, 1899, with a report on the case of “cigarette fiend” Charles Cross. (Photo: Library of Congress)

The public was outraged by the vicious crime, but also confused; surely such a young boy, particularly one who had no recorded history of violence, could not have done this and been in his right mind. It had to be mental instability – and they didn’t have to look far for a cause. “The boy is not responsible. His mind is diseased,” claimed Dr. Simon, just before Cross’ sentencing. “Any boy that smokes one hundred cigarettes in a day is bereft of moral self-control.”

Similar pleas were published in newspapers across the country, and everyone from the governor to the Board of Pardons received petitions begging mercy for this “moral degenerate.” Unfortunately for him, Cross was hanged on July 20, 1900, 19 days after his 18th birthday. He was one of the youngest people ever sentenced to death in Connecticut.

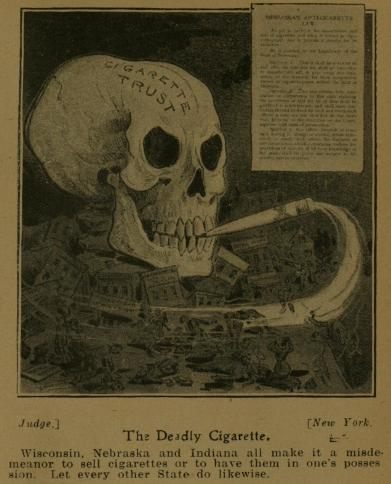

An anti-smoking advertisement from 1905. (Photo: Public Domain)

This carcinogenic “Twinkie defense” lasted well into the 1910s, especially where juvenile delinquents were involved. Study after study flooded newspapers about the number of boys in prisons or hospitals thanks to “their minds [being] weakened by the excessive smoking of cigarettes.” Reform schools insisted “the most hardened of the boys were all cigarette fiends,” and “more than any other one factor starts [them] on the road to criminal life.” It took World War I, when the ease and convenience of pre-rolled cigarettes followed soldiers home from war, to stub out their evil reputation.

Still, you might want to steer clear of Uncle Ted, just in case.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook