Islands of The Undesirables: North Brother Island

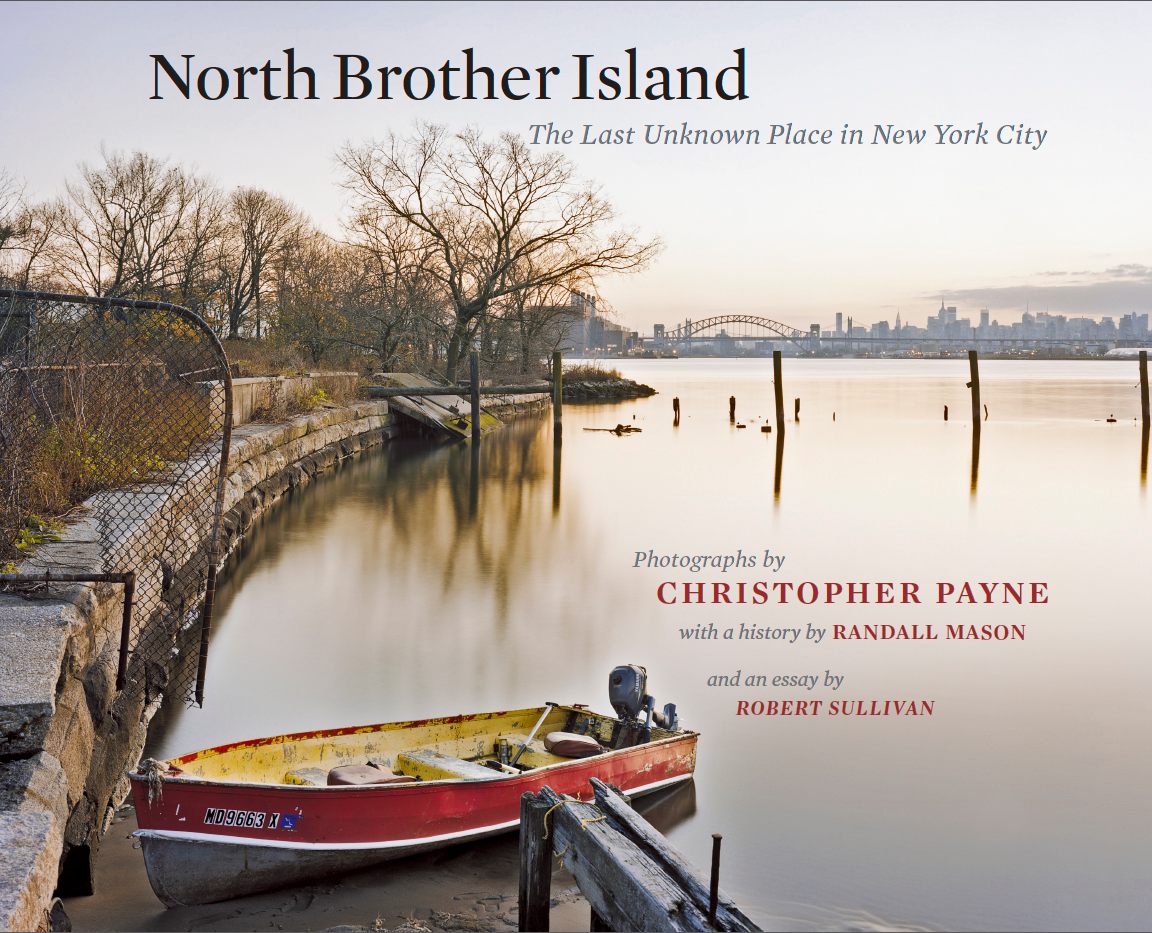

The view from North Brother Island at dusk. (Photo: Christopher Payne)

The view from North Brother Island at dusk. (Photo: Christopher Payne)

This is the third installment of a five-part series about NYC”s Islands of the Undesirables, the hidden-in-plain-sight places that we have used for asylums, prisons, detention centers, medical research facilities and other unsavory destinations right on the edge of glittering Manhattan. The series is based on an Obscura Day event. Monday was Roosevelt Island, and yesterday we looked at Randall’s and Wards Island. Today, we’re bringing you to North Brother Island in the Bronx.

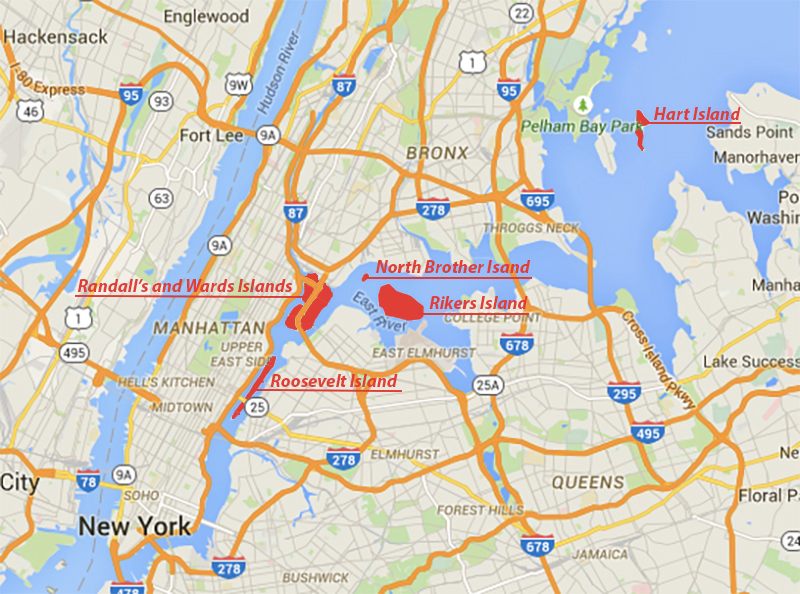

A map of the islands that are featured in Atlas Obscura’s Islands of the Undesirables series (Photo: Map Data © 2015 Google)

North Brother Island is an uninhabited patch of land located smack dab in the middle of the East River between the Bronx and Rikers Island. It was the site of the infamous Riverside Hospital for quarantinable diseases—the place where Typhoid Mary finally succumbed to her namesake illness in 1938. After WW2, up until 1951, the island was repurposed as housing for veterans and their families. The island then played host to a rehabilitation center for adolescent drug addicts. After the facility closed in the 1960s (amid allegations of corruption) the island became a bird sanctuary, permanently closed off to the public.

But photographer Christopher Payne has been able to spend years documenting the place, as he was granted access to document the island by the New York City Department of Recreation in 2006. His haunting photos, taken over a few seasons, illustrate the inevitable decay of architecture in a place devoid of humans. Payne’s work is featured in his book North Brother Island: The Last Unknown Place in New York City.

Nature has reclaimed the buildings. (All photos: Christopher Payne)

Can you give us a pocket history of North Brother Island? Who lived there before Europeans, how did it get its name, etc.?

At first glance NBI is the most unexpected of places: an uninhabited island of ruins in New York City, a secret existing in plain sight that hardly anyone knows. Yet it was once an ordinary part of the city, and for over eighty years, from the 1880s until its abandonment in 1963, thousands of people called it “home”.

The navigator Adriaen Block, the Dutchman who explored the Atlantic Coast between 1611 and 1614, named North Brother and its smaller sibling, South Brother, “de Gessellen”, which translates as “the wayfarers” or the “journeymen” or “brethren,” or in the usage that New York City maps retain today, “brothers.”

Little is known about North Brother before the mid 19th century, and it seems to have served no formal use until a lighthouse was erected on the southern portion in 1869. In the 1880’s it began to get more attention, as public health issues of an exploding population regularly made headlines. Like other islands in the harbor, it was perfectly suited as a buffer against contagions, and from the 1880s through the 1930s it was used primarily as a quarantine hospital (the infamous Typhoid Mary was confined there). After WWII it provided a temporary home for veterans and their families, and from the 1950s it was used as a juvenile drug treatment center until its closure in 1963. Over the years, new uses have been proposed for the island, but by and large it has been forgotten. Thanks to a threatened species of shorebird, the black-crowned night heron, North Brother has been designated as conservation land, to protect nesting grounds for the herons, which have unwittingly helped to preserve the island’s forgotten fragments of New York’s history. Today the island is overseen and maintained by the New York City Parks Department.

The spiral staircase in the Nurses Home.

The Tuberculosis Pavilion lobby, which was part of an infamous quarantine unit where Typhoid Mary died.

What stands out about that history to you? What do you think is special about North Brother Island?

Its history is really not much different from any of the other harbor islands used for social welfare purposes—in New York and other American cities. What I find special about North Brother is the splendid sense of isolation you feel when you penetrate the perimeter vegetation and arrive in a peaceful, canopied forest. The juxtaposition of decaying buildings with the lush landscape makes for a sublime experience.

It’s also a window into the future, into a city without people, as if people suddenly vanished.

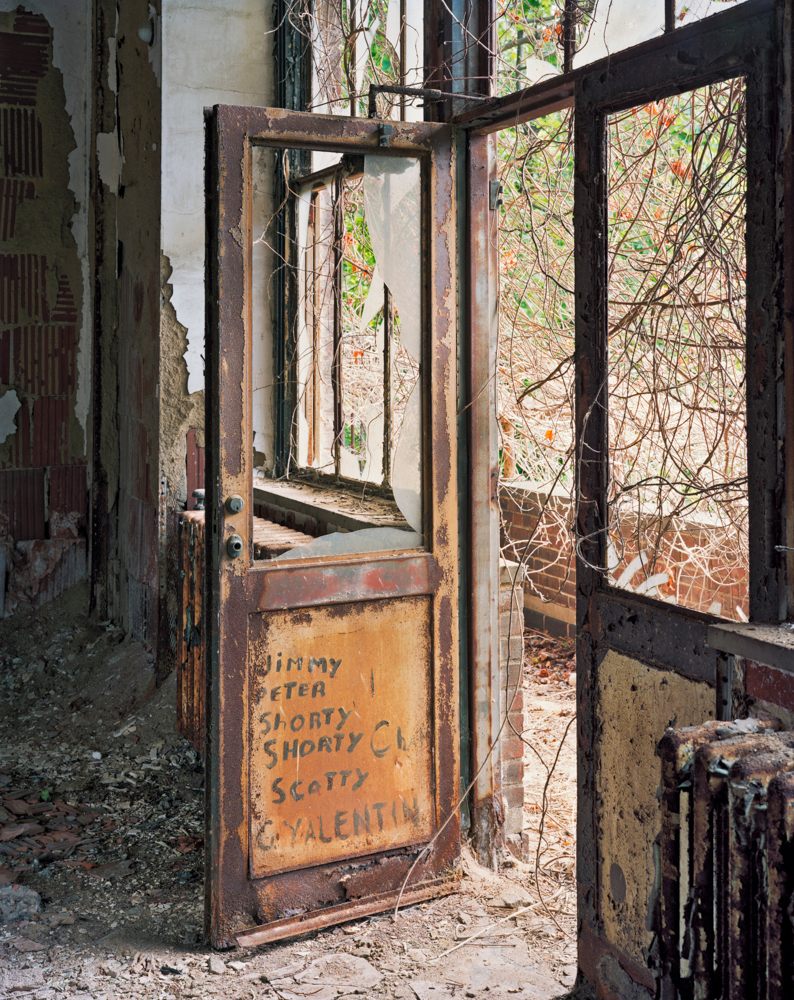

A door with patient’s names carved in abandoned Tuberculosis Pavilion .

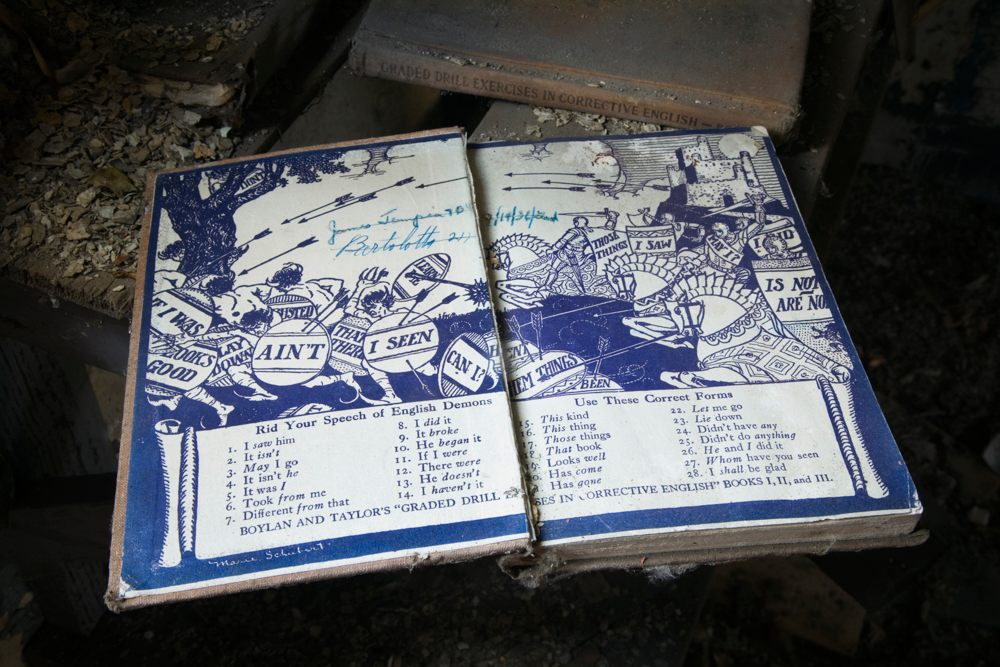

An English grammar book from the 1930s.

When did you start visiting? How did you find out about it?

I first learned about North Brother in 2004, when I was commissioned to photograph industrial sites along the East River by the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance. The island’s unique ruinous landscape immediately appealed to me, given the similar work I was doing at the time on abandoned state mental institutions.

After an initial trip with the NYC Parks Department, I was hooked, and in 2008 they granted me approval to take pictures. The deal we struck was that I would provide transportation in return for access (they didn’t own a boat, but I had a friend who did!). And so from 2008 to 2013, my friend Todd would drive up from Washington DC, with a boat strapped atop his minivan, and ferry us back and forth. We probably made at least two-dozen trips in all.

The only remaining side of the island’s church.

What did it feel like to visit somewhere that has had no continuous human presence for 45 years, and that has such a dark and sad history?

As a photographer, it was frustrating, because the buildings are very dilapidated and few artifacts remain to indicate how the spaces were last used. Everything portable of value has been stripped away by vandals. Nature and neglect have done the rest.

Walking amid such empty, “charged” spaces, it’s easy for our imagination to fill the void and assume the worst. Yet when I spoke with a veteran and his wife who lived on the island as newlyweds just after WWII, they recalled it fondly as an idyllic place to raise a family. I also met a man who was sent there in the 1950s as a drug addicted teenager. He said his experience there—and the compassionate care he received from a social worker—changed his life and helped him kick his habit for good.

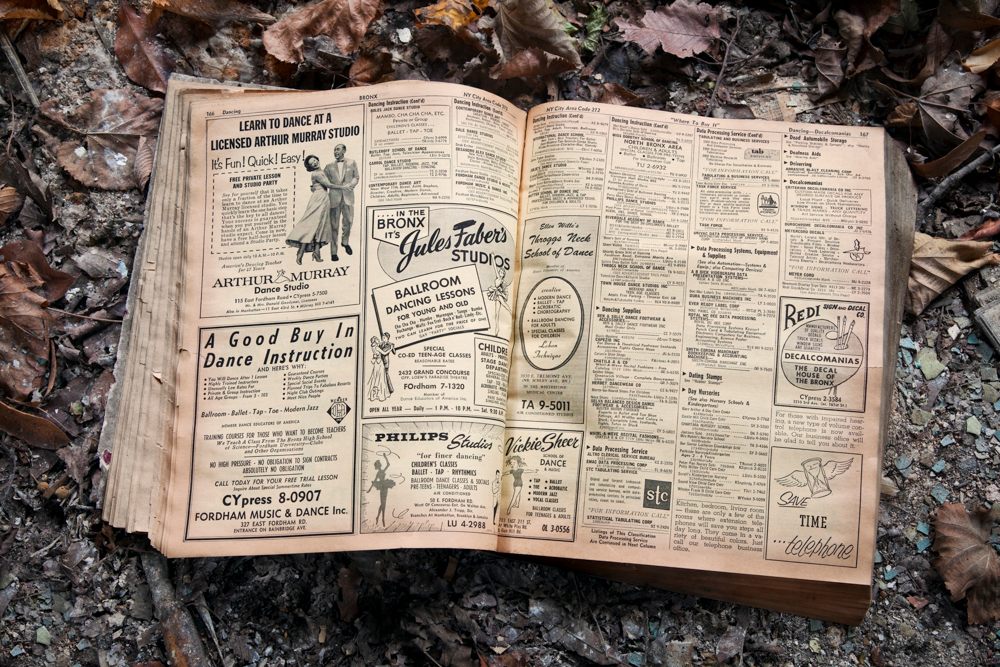

A Bronx Yellow Pages (now burnt orange).

A Bronx Yellow Pages (now burnt orange).

The auditorium of the Service Building.

The auditorium of the Service Building.

What were some of the challenges when shooting somewhere so dilapidated? What kind of precautionary measures did you have to take?

Most of the buildings were in very bad shape so we had to be careful where we walked. Floors and roofs were caved in, stair treads were missing—the usual dangers one encounters. But the real challenge was poison ivy, which seemed to be everywhere. As a precaution, I’d wrap my equipment in plastic bags. Over the years, I came to enjoy shooting in the late fall and winter more than summer. It was easier to get around, and the buildings weren’t covered in vegetation, allowing light to get inside.

Boiler roof interior.

Why do you think people are fascinated with ruins?

This is a very broad question: they’re evocative, romantic, spooky, etc. The list goes on and on. My interest in ruins is a by-product of the subjects I am most drawn to: industrial infrastructure and processes, and older buildings. Many of these places were designed for a specific purpose at a particular time. Over the years, they have become outdated and obsolete. North Brother Island is a perfect example as a quarantine hospital for infectious diseases. The need for a self-contained island community, in the middle of New York City, simply doesn’t exist anymore.

The exterior of the Tuberculosis Pavilion, the legendary quarantine facility.

The exterior of the Tuberculosis Pavilion, the legendary quarantine facility.

What do the ruins of North Brother Island show about New York City in the late 1800s?

North Brother Island was one of many institutions (public schools, asylums, hospitals, universities, prisons) erected in the late 19th century in New York City as a social buttress to counter the perceived ills of disease, urbanization, immigration, and population growth. This kind of civic investment, whatever its motivating cause, was executed on a scale unheard of now. The location and use of North Brother Island, as a quarantine hospital, also speaks about the city’s social geography and how it was organized much differently than it is now. Back then, less savory people, activities, and neighborhoods were relegated to the peripheries of the city, like the waterfront and islands. Now these edges have been reclaimed as coveted land for public access and high-end living. It’s basically an inversion of the old order.

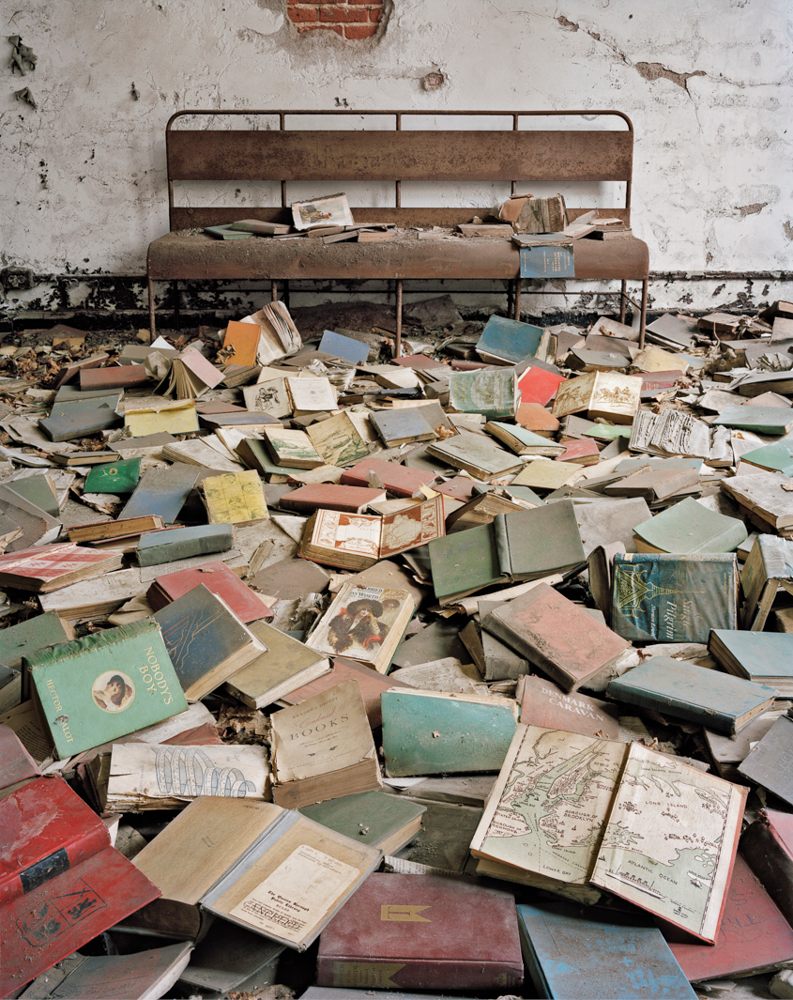

A classroom with books.

A classroom with books.

Tuberculosis Pavilion balcony.

Do you think public access should be allowed?

I think access should be allowed but I hope the island will be preserved as a natural sanctuary. I would love to see the Tuberculosis Pavilion restored and adaptively reused, with the other structures stabilized as ruins, like the smallpox hospital on Roosevelt Island. Buried sidewalks and roads could be cleared, but not too much so that it becomes sanitized like Ellis Island. That’s what makes North Brother so wonderful: it’s isolated and wild, and moving along at its own natural pace, separate from the rest of the city.

A street on North Brother Island.

Update, 6/3: The original version of this article misidentified that the island was abandoned until the 1950s.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook