Islands of The Undesirables: Roosevelt Island

Aerial view of Roosevelt Island (Photo: Philip Capper/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

Aerial view of Roosevelt Island (Photo: Philip Capper/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

In 1883, Emma Lazarus wrote “The New Colossus,” a poem that would eventually be engraved on a plaque on the Statue of Liberty. In her famous lines, Liberty herself—the “Mother of Exiles”— declares:

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

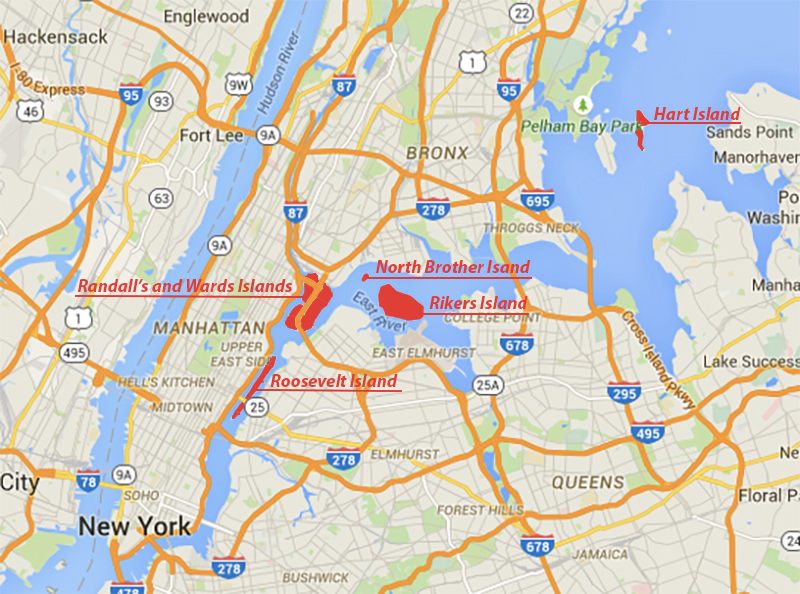

While the words are appropriate for Ellis Island, other islands around New York City seem to operate with a different message. These are places to which the “wretched refuse” have been banished, not welcomed. Roosevelt Island, Randall’s Island, Ward’s Island, Rikers Island, and Hart Island have all been places where the tired, poor, sick and criminal are sent to be treated—or sometimes just confined—far from glittering Manhattan. The water has served as a kind of moat, as well as insurance against NIMBY protestations. These islands aren’t part of anyone’s backyard, which has made them a perfect place for the unwanted, nestled in plain sight of one of the world’s great cities.

A map of the islands that are featured in Atlas Obscura’s ‘Islands of the Undesirables’ series (Photo: Map Data © 2015 Google)

This is the first part of a five-part series based on this past weekend’s Obscura Day event. First up: Roosevelt Island.

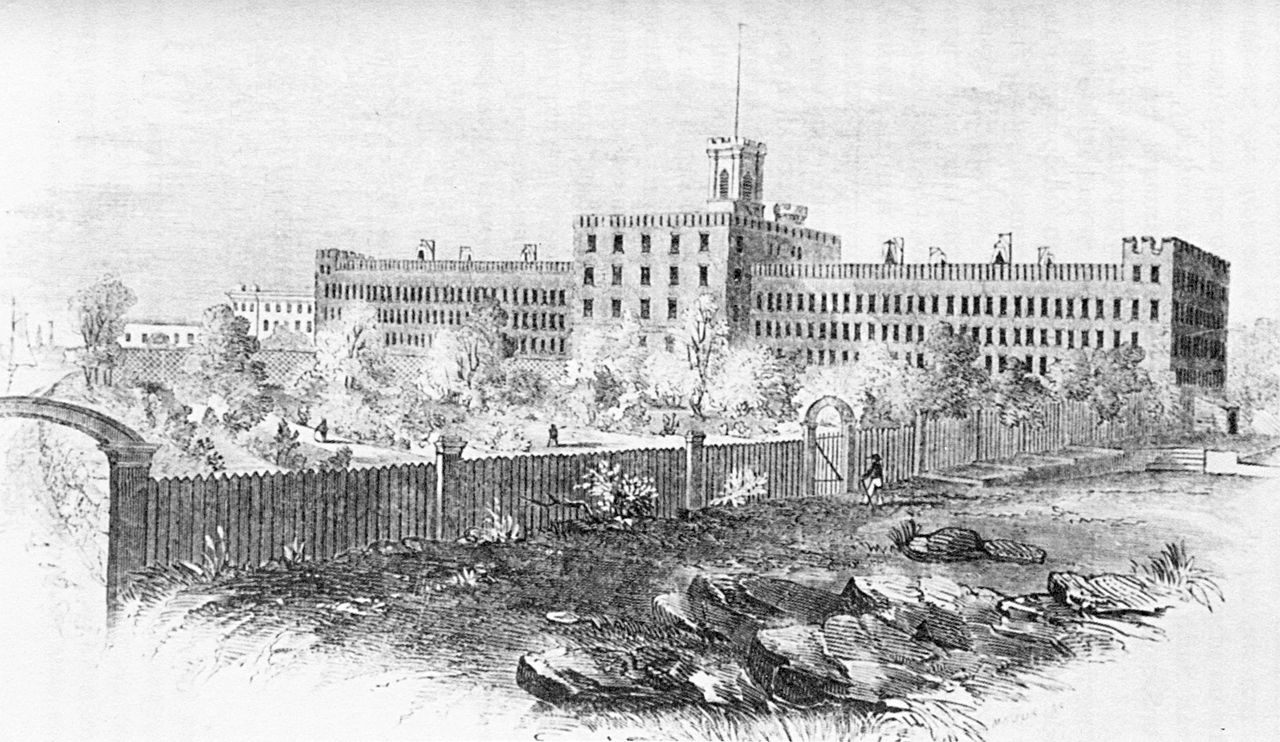

Prison and garden on Blackwell’s Island (today Roosevelt Island),

1853 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

According to most sources, the original inhabitants of what is now Roosevelt Island, the Canarsie tribe, called the place Minnahannock, which translates to “it’s nice to be here.” (As with many things reported about Native Americans during this time period, it’s wise to take this with a grain of salt.) The Dutch called the place Varcken Eylandt, or Hog Island, because they raised hogs there, while the British called it called Manning’s Island, after Captain John Manning, who owned the island starting in the 1660s.

It was during the tenure of Manning’s son-in-law, Robert Blackwell, that the island came to have darker associations, becoming the site of lunatic asylums, prisons, and other institutions.

The first European owner of the island was Wouter Van Twiller, the Director General of the New Amsterdam colony, who bought the island from the Canarsie tribe, as he did with what’s now Ward’s, Randall’s, and Governors Islands. Once the English took over, they granted the island to John Manning, sheriff of New York, but he ended up in disgrace. In 1673, while commanding Fort James, Manning surrendered the colony to the Dutch (to be fair, he only had about 80 men to defend the place). The English sent him back to the mother country to be court-martialed, then to New York to be publicly disgraced, with his sword broken in a City Hall ceremony. Manning was told he could never hold public office again, and banished to his island. According to one Rev. Charles Wooley, written about in a book called The Other Islands of New York by Stuart Miller and Sharon Seitz, the former sheriff’s chief entertainment was “commonly a Bowl of Rum-Punch.”

The island’s next owner and namesake was Robert Blackwell, who married Manning’s daughter Mary. A house built by his descendants still stands on the island, and is the sixth-oldest house in New York City. It looks forlorn but well-maintained, the glass wavy with the pressure of centuries. The Blackwell family lived and farmed on the island into the 19th century, although they repeatedly tried to sell it without any takers.

The house built for James Blackwell between 1796-1804 still stands on Roosevelt Island (Photo: Doug Kerr/Flickr)

The house built for James Blackwell between 1796-1804 still stands on Roosevelt Island (Photo: Doug Kerr/Flickr)

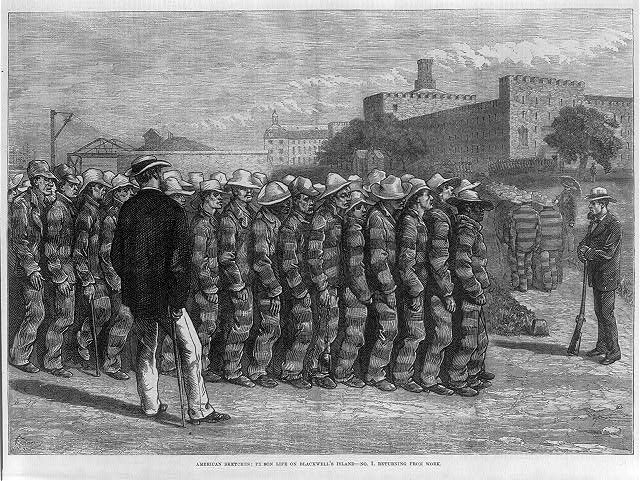

Finally, the city bought the whole island in 1828 as a location for charitable and corrective institutions. Their plan was to create a “city of asylums.” In part this was a desire to create more humane institutions for the criminal and the mentally ill, although these places don’t necessarily look humane to today’s eyes. Within a few years of the purchase, two fairly grim institutions opened up—a penitentiary and a lunatic asylum. While the island was eventually home to more than a dozen different institutions, these two are among the most storied. The penitentiary was erected as a state prison in 1832, and by the early 1900s there were a series of scandals involving inmate overcrowding, drug-dealing, and favoritism. Riots and escape attempts were common: there are reports of people breaking off doors to use as floatation devices on their way to Manhattan, and gangs of nude men swimming for their freedom. A report issued in 1914 by Correction Commissioner Katharine Davis (incidentally, the first woman to head a New York City Agency) described the penitentiary as “vile and inhuman” and “wet, slimy, dark, foul.” Later that year, 700 of the 1,400 prisoners joined an uprising that lasted for days.

Prisoner’s returning from work to Blackwell’s Island, 1876 (Photo: Library of Congress)

One small, but telling, example of the endemic corruption is the fact that two mob leaders imprisoned in in the 1930s kept flocks of homing pigeons in the prison for smuggling drugs and messages. One was Joseph Rao, a Harlem racketeer and member of the Dutch Schultz gang, who turned the prison hospital into his headquarters, where he enjoyed silk shirts and dressing gowns, lilac toilet water, monogrammed stationery and his own pet goat. He kept his homing pigeons on the roof, while Irish mob leader Edward Cleary was less extravagant and kept the pigeons in his room.

Other celebrity prisoners include Emma Goldman and Mae West, the latter sentenced after complaints about her play Sex. She dined with the warden and his wife every night, and her prison labor consisted of dusting the books in the library. On her release, she gave only one interview, to the magazine Liberty, for which she charged $1,000 and donated the proceeds to the establishment of the Mae West Memorial Prison Library.

By 1921, there had been enough scandal that the city hoped changing the name to “Welfare Island” would provide an image boost. But there wasn’t any real reform until the 1930s, under Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia. He appointed a new Commissioner of Correction, Austin H. MacCormick, who conducted a surprise raid on what he called “the worst prison in the world.” As the New York Herald Tribune described it at the time, “boss gangsters lived in luxury, swaggered around, and at the same time there was an almost incredible condition of misery and degeneracy.” After MacCormick raid, the inmates were moved to new facilities on Rikers Island, and the prison was demolished.

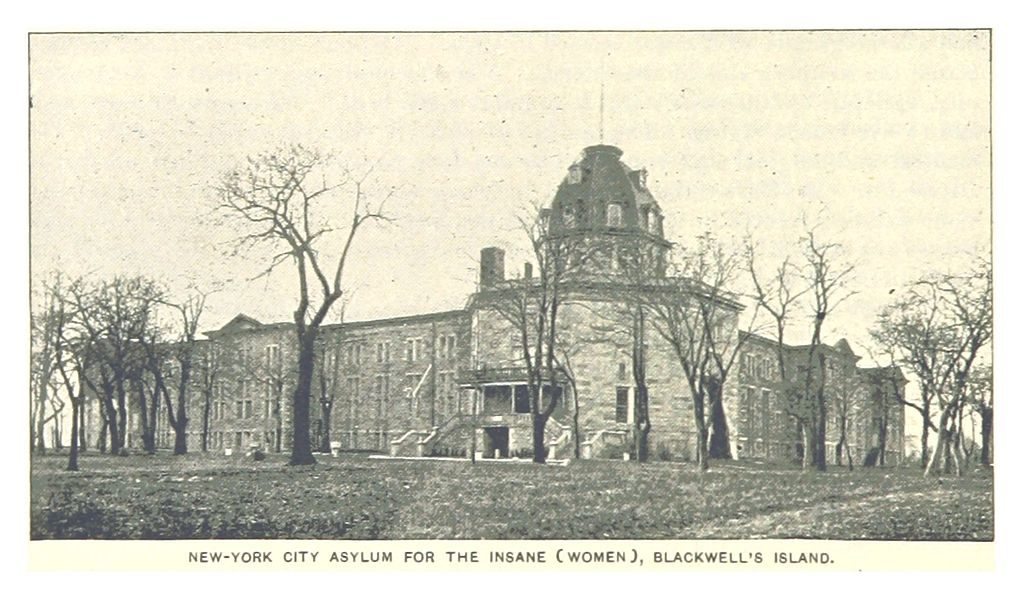

The lunatic asylum, parts of which still stand, is another story. It opened in 1838 as a humane refuge for the insane, although there doesn’t seem to have been much actual treatment—mostly patients were just supposed to rest. Women outnumbered men two to one, in part because some husbands committed their insubordinate wives.

The asylum on Roosevelt Island, c 1893 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

No less than Charles Dickens visited not long after the opening (as a tourist, not a patient). In his American Notes of 1842, he wrote:

“Everything had a lounging, listless, madhouse air, which was very painful. The moping idiot, cowering down with long disheveled hair; the gibbering maniac, with his hideous laugh and pointed finger; the vacant eye, the fierce wild face, the gloomy picking of the hands and lips, and munching of the nails: there they were all, without disguise, in naked ugliness and horror.”

An 1866 account in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine was a little more cheery: it reported that patients caught lobsters and fish, played quoits, built furniture and grew their own vegetables, including 200 bushels of tomatoes a year. Patients were also enjoying new clothes—instead of wearing striped outfits like that of the nearby penitentiary inmates, the men wore navy blue get-ups and the women calico gowns. That may have been little comfort for one woman who, according to Harper’s, thought she was a china teapot, and sat for hours each day with her right arm positioned as a spout and her left as a handle, always in fear she would be knocked over.

The asylum’s most famous patient visited in 1887. That year, journalist Elizabeth Cochrane (better known under her pen name Nellie Bly) showed up at a women’s boarding house in the city pretending to be an insane Cuban immigrant. She was committed to the asylum, where she spent more than a week gathering notes for what would become her famous expose, Ten Days in a Madhouse.

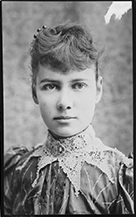

Elizabeth Cochrane (pen name Nellie Bly) c. 1890 (Photo: Library of Congress)

Elizabeth Cochrane (pen name Nellie Bly) c. 1890 (Photo: Library of Congress)

Cochrane described the asylum as “a human rat-trap,” with “oblivious doctors” and massive orderlies who “choked, beat and harassed” patients. According to Bly, anyone who wasn’t already insane would be driven crazy by the enforced isolation, rancid food, dirty linens, plentiful rats and buckets of ice-cold water frequently poured over them. Bly dropped her “crazy” act as soon as she arrived at the asylum, but still had to be freed by an attorney. The exposé, which ran in The New York World and still serves as a landmark in investigative journalism,led to a grand jury investigation and a massive increase in the Department of Public Charities and Corrections budget, which helped improve conditions.

The cover of Nellie Bly’s “Ten Days in a Mad-House”, published in 1887 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The asylum moved to Wards Island not long after that, and the building became the Metropolitan Hospital, which in turn left for Harlem the 1950s. But the original asylum’s octagon, built of blue-grey local schist, still stands and is now a part of an upscale apartment complex near a beautiful community garden.

Other 19th century facilities on the island included an almshouse and a hospital, which later became City Hospital, for a time the largest hospital in the country. The nurses and servants there were mostly people who had originally been confined to the almshouse; according to one report, they received “no wages but a pretty liberal allowance of whiskey.” A smallpox hospital, built by James Renwick Jr. (the architect of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan) in the 1850s still stands on the tip of the island. Known as Renwick’s Ruin, it’s fenced off so that visitors can’t come too close to the dilapidated structures now inhabited by cats, but they still make a beautiful, ivy-covered sight.

The remains of the Smallpox Hospital (Photo: Jessica Spengler/Flickr)

The remains of the Smallpox Hospital (Photo: Jessica Spengler/Flickr)

Another interesting building on the southern tip of the island is the Strecker Memorial Laboratory, constructed in 1892 as the nation’s first institution devoted to pathological and bacteriological research. A special division of City Hospital, it was solely devoted to studying infectious conditions. There was a specimen examination room, autopsy room, mortuary, library, and even a museum. Later it became the Russel Sage Institute of Pathology, before closing in the 1950s. The MTA took it over in the late 1990s to house a substation.

Detail of the Smallpox Hospital ruins (Photo: Bess Lovejoy)

Detail of the Smallpox Hospital ruins (Photo: Bess Lovejoy)

Nowadays, the asylums, research labs and prisons have given way to, of course, condos. In 1969, the city leased the island to New York State’s Urban Development Corporation for 99 years. Their idea was to build a residential community they referred to as the “new town in town”—a vision that eventually came true. The island, whose name was changed to Roosevelt in the early 1970s, is now home to more than 10,000 residents, with five public parks and a popular tramway, tennis club, sculpture center, festivals, and thriving volunteer organizations.

The change for the island came slowly, but by the 1980s it became a relatively desirable place to live, known for being peaceful and offering great views of Manhattan, once only offered to those banished from its center.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook