A New Monument Celebrates Nellie Bly’s Undercover Reporting, Right Where It Happened

The Roosevelt Island artwork pays homage to her reporting, especially her inside look at a city asylum.

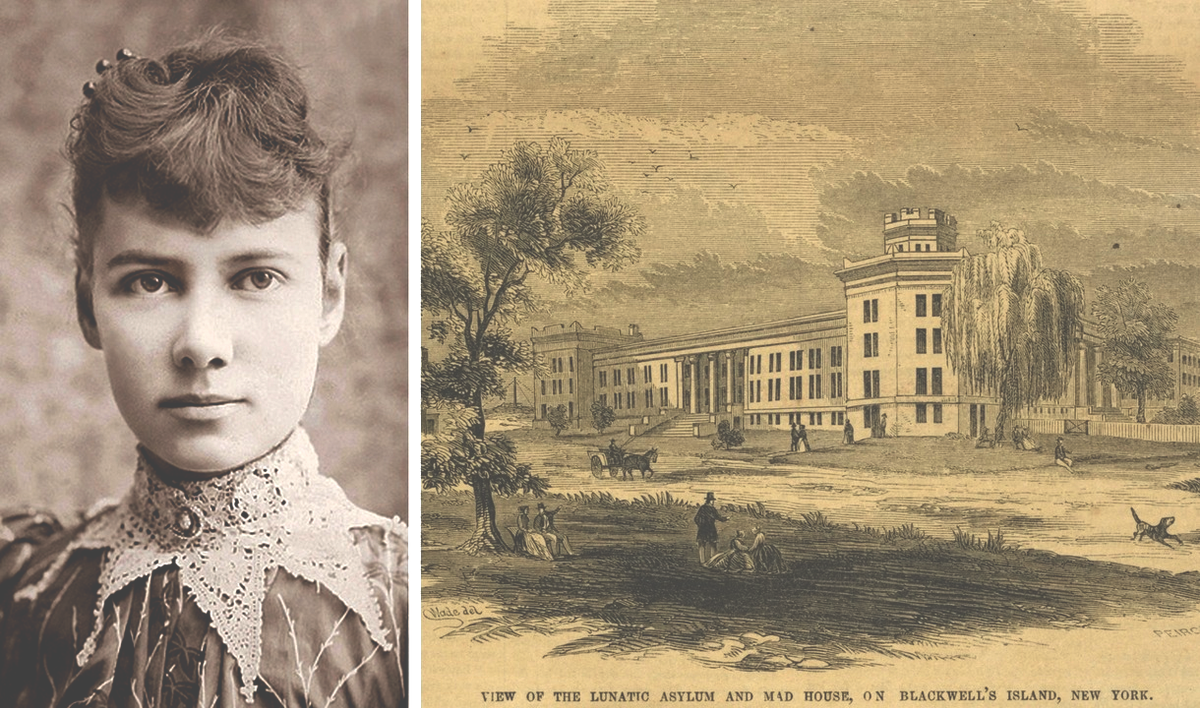

In the late 1880s, the reporter Nellie Bly faked her way into an asylum on Blackwell’s Island, in New York’s East River. (The native Lenape people knew the landmass as Minnehanonck, and it was renamed Roosevelt Island in the 1970s.) On assignment for the New York World newspaper, Bly, who was born Elizabeth Cochran Seaman and became one of America’s earliest and most intrepid female investigative journalists, reported on the people who were housed there by playing a patient herself.

Bly’s harrowing account was titled “Ten Days in a Mad-House,” and it described horrid food—inedible oatmeal and blackened, spider-studded hunks of unbuttered bread—and deplorable conditions, such as silent, stiff hours on crowded benches and uncomfortable trips to a frigid bathroom, where she and other patients were scrubbed until “my teeth chattered and my limbs were goose-fleshed and blue.” More than 130 years later, the writer has returned to the island in the form of a monument to her work and the subjects she championed.

Sculptor Amanda Matthews, co-owner of the firm Prometheus Art, designed the piece, which was installed at the north tip of the island in late 2021. It consists of a long walkway that stretches past several mirrored spheres and four seven-foot-tall faces, representing a young girl, an African-American woman, an Asian-American woman, and a queer woman. Each is cast in bronze and cleaved elegantly apart like enormous jigsaw pieces. The walkway leads to a statue of Bly herself, cast in a silver bronze. Matthews titled her installation The Girl Puzzle, a nod to the headline of Bly’s first published article, a thoughtful, passionate 1885 piece in the Pittsburgh Dispatch in which Bly advocated for solid, stimulating, paying jobs for women workers, and it is etched with her words.

Faces loomed large in Bly’s work: She was captivated by her subjects’ faces, and also made detailed notes about the staggering size of the eyes, nose, and ears of the giant Buddha that she encountered on a trip to Kamakura, Japan. “I thought, ‘Wow, this idea of what could be seen on faces was really something to her and her writing,’” Matthews says. Her depiction of Bly’s face is partly inspired by strong, thoughtful, and visionary gods in Greek, Norse, or Roman mythology. The artist also thought that Bly’s famously unruly bangs evoked the laurel wreaths that often crowned their heads.

The other faces in the installation don’t reference particular people Bly met through her reporting. Instead, Matthews drew from people in her own life. “It came to me almost like a wave over me,” she says. “I could see the faces, and would get up in the middle of the night and go to my computer.” Inspirations include Matthews’s own daughters, a friend who lost her child, and the mother of Matthew’s studio assistant, who was forced into a concentration camp for Japanese Americans during World War II.

Public art has a notorious diversity problem, and the subjects of most New York City sculptures are still overwhelmingly white and male. In 2019, a paltry five women from history were commemorated in outdoor public art across the five boroughs, the New York Times reported. The paper noted that statues of four more women were in the works across the city: A sculpture of singer Billie Holiday, in Queens; one of pediatrician and public health advocate Helen Rodríguez Trías, in the Bronx; one of teacher Elizabeth Jennings Graham, whose protests helped spur the desegregation of the city’s streetcars, in Manhattan; and one of lighthouse keeper Katherine Walker, on Staten Island. Matthews views her installation as a chance to celebrate Bly as well as women whose accomplishments and struggles have been shunted to the margins of history. “They don’t have a lot of stories written about them,” Matthews says. “They certainly don’t have a lot of sculptures honoring them.”

In the 19th century, women could be confined in squalid asylums merely because they were perceived as different, or even because they were non-native English speakers who struggled to communicate with doctors or authorities. Bly left a legacy on the island: Her exposé was widely read and shifted city policy. Today, the main vestige of the asylum is an octagon-shaped tower, which was once an entrance to the structure, and is now part of a luxury apartment building. But this new monument makes the painful past Bly documented visible again.

A version of this story originally appeared on January 8, 2020. It was updated in March 2022 to include information about the installation of the monument.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook