The Anthropologist Who Has Spent 50 Years Protecting—and Learning From—Orangutans

Biruté Mary Galdikas has quietly fought on the frontlines of some of conservation’s biggest battles.

For Women’s History Month, Atlas Obscura’s Women in Conservation series celebrates women of science who are protecting our planet’s biodiversity in innovative ways.

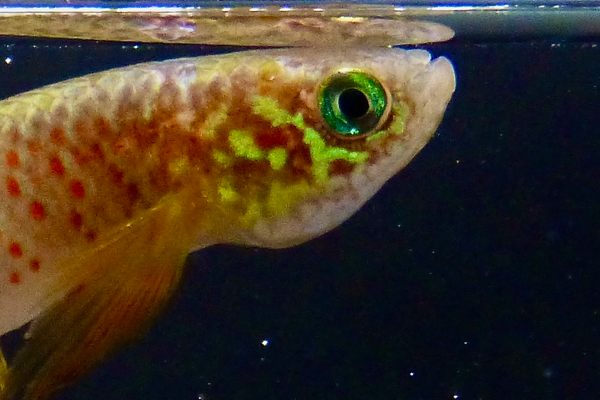

The cigarette butts and plastic wrappers were the first warning signs. The trash, found deep in the rain forest of Southern Borneo’s Tanjung Puting National Park in the late 1990s, was worrisome evidence that a new batch of poachers was on the prowl. Over several decades, the region had been hit by illegal loggers and rampant, unregulated fishing of the endangered Asian arowana, or dragon fish. Slash-and-burn clearing for palm oil plantations and open-pit gold mining continued to bite into the borders of the protected land. Now hunters were targeting orangutans, either to capture them for animal trafficking or simply to kill the primates as an “agricultural pest.”

Biruté Mary Galdikas and her team were ready for them.

As they had when facing past threats, Galdikas and rangers from Orangutan Foundation International (OFI), which she cofounded in 1986, sprang into action, lobbying the government, raising alarms, and forming partnerships with regional police, who were reluctant to venture into the wilderness on their own. Galdikas even led some of the patrols, sometimes sneaking up on poachers’ makeshift shelters in a Zodiac boat powered by a quiet electric motor. Despite some success and continued vigilance, the threat of poaching continues today—as does her resolve. Since her first venture into the field more than 50 years ago, Galdikas has never stopped her work, or her advocacy for the animals and people who call the rain forests home.

In the early 1970s, the media dubbed Galdikas one of “Leakey’s Angels,” a reference to the trio of young women who had secured funding for primate research from famed anthropologist Louis Leakey. Also known as the “Trimates,” the group included Jane Goodall, who went on to fame for her observations of chimpanzees before trading fieldwork for high-profile conservation outreach and environmental activism in the 1980s. The other member of the trio, Dian Fossey, continued her research on mountain gorillas until her murder in 1985. Both women are household names today, but it is the lesser-known Galdikas who may have the greatest impact on primate science and community-forward conservation. Born in Germany to Lithuanian parents, raised in Canada, and educated there and in the United States, Galdikas would find her true home, and her calling, in Borneo.

At the University of California, Los Angeles, her professors warned her that her plans to observe orangutans in the wild were unrealistic; the animals lived in difficult, often swampy terrain that would be impossible to navigate. But upon arrival at Tanjung Puting in November 1971, Galdikas, then 25, threw herself into the unglamorous work—and the mud. “Days were spent in the swamps, up to our armpits in black acidic water,” she later wrote. “Insect bites that led to inflamed sores, malaria, and mysterious fevers were very common occurrences. Once … a centipede bit me on the face and my face swelled up so much that I looked like an old potato.”

She quickly learned how to gain the trust of the area’s wild orangutans and, within two months of starting the work, was the first person to observe an individual for more than a day. In fact, Galdikas followed an orangutan and her infant for five days, venturing ever deeper into the forest. It yielded the first of her countless discoveries about the animals’ social behavior, diet, tool use, and more. She also created an orangutan rehabilitation and release program that has since returned more than 500 animals—most caught by poachers—to the wild.

While Galdikas was establishing herself as the world’s leading expert on orangutans—our closest living relatives after chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas—she was also forging a new way to involve local people in conservation science and application. She earned a reputation for building lasting partnerships with Indigenous communities, and for recruiting and training their members as rehabilitators, research assistants, and rangers. More than 200 locals, most from the Dayak ethnicity, now work for OFI in Indonesia. Galdikas was also instrumental in elevating Tanjung Puting from a game reserve to a national park in 1982 and, in 1997, became the only foreigner ever to receive Indonesia’s highest honor for environmental stewardship. Soon after, as she closed in on 40 years in the field, Galdikas earned another distinction. The research she has led in Borneo has become the world’s longest continuous field study, run by a single principal investigator, of any wild mammal.

The woman known for her practicality and determination is not one to rest on her laurels, however. As orangutans and their ecosystems—home to myriad other species—continue to be hemmed in by deforestation and threatened by poaching, climate change, and other menaces, Galdikas has been increasingly vocal about larger environmental causes.

“I became a researcher to study orangutans, and I soon learned you can’t ignore the habitat that sustains them,” she said upon winning another sustainable development award in 2021. “In order to keep the species, or any species, for that matter, from irreparable harm, we need to understand that connection to nature. I’ve made it my life’s work.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook