The Mughal Women Who Wouldn’t Stay in the Harem

From musket-wielding empress Nur Jahan to writer Gulbadan Begum, meet the influential women of the early-modern Muslim empire.

In Atlas Obscura’s Q&A series She Was There, we talk to female scholars who are writing long-forgotten women back into history.

It was a cool fall day in 1619 when the empress and emperor of India set out from Agra. Their itinerant court, 150,000 people and 10,000 elephants strong, marched toward the Himalayan foothills. But, as servants began to pitch the elaborate imperial tents, a group of local hunters begged for help—a man-eating tiger stalked their home. The emperor, Jahangir, had vowed to give up hunting and could provide no help. But the empress, Nur Jahan, a famed markswoman, stepped in. On October 23, 1619, armed with an exquisite firearm and seated atop an elephant, the empress searched for any sign of the tiger in the dense forest. When the powerful cat emerged, Nur’s elephant tried to flee, jostling the empress’s litter. She lined up the shot and pulled the trigger. The tiger fell. One shot was all she needed to kill the beast.

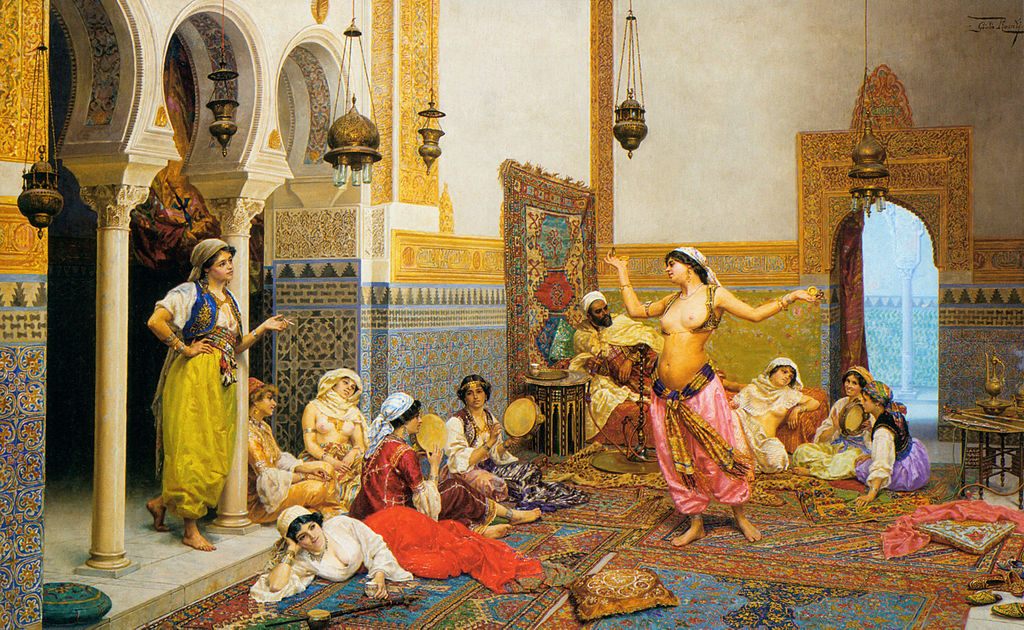

“A woman shooting publicly was rare; a woman shooting with such expertise was unheard-of,” writes historian Ruby Lal of Emory University, author of Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan. But Nur Jahan’s skill with a gun wasn’t the only reason the empress stood out. For more than a decade, Nur Jahan co-ruled India alongside her husband, the fourth Mughal emperor. Though Nur Jahan was the only woman to rise to the status of co-sovereign, many other contemporary elite Mughal women rose to prominence and exercised political power in the Muslim empire that ruled much of India between the 16th and 19th centuries. Even though Jahangir’s father, the emperor Akbar, created the first imperial harem, women who were not empresses held sway from behind its walls.

Atlas Obscura talked with Lal about the power of these elite women, the many misconceptions of the imperial harem, and Nur Jahan’s incredible hunting skills.

What was life like for Mughal noblewomen?

In the early days of the dynasty, people were migratory. Mughal women were very much part of the movement of tented living, participating in deliberations of strategy. Women, as they got older, served as counselors, advisors, and peacemakers.

The younger women a lot of the time were pressed to produce children because the longevity of the empire rested upon producing children, preferably boys. But birthing children was more like a political act. In this dynasty, there was no law of primogeniture, that is, the eldest didn’t automatically become the king. So the princess had to do a variety of things. They had to train their boys as governors. The boys had to be militarily skilled. They had to have supporters. So there was a lot at play in the raising of these children.

What prompted the third Mughal emperor, Akbar, to create the first Mughal harem?

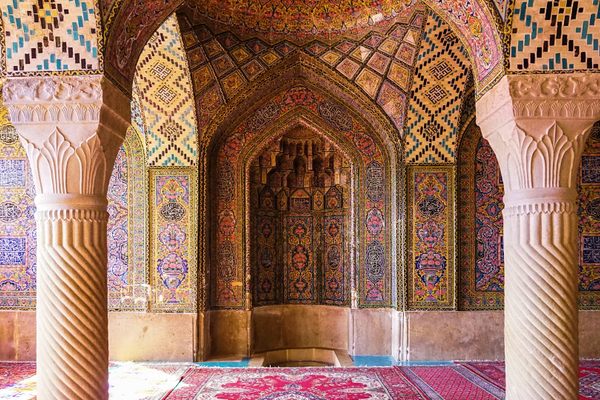

Akbar the Great builds the first imperial harem just outside of Agra. He moves away from the migratory, peripatetic, nomadic character of his forefathers. The idea of the harem itself is brilliant because it is not just confining the women behind the walls. The first definition of the harem is attached to the sacred cities of Mecca and Medina, which are the cities of the Prophet Muhammad. Akbar’s chronicler actually says that emperor is divine. So Akbar’s using all these ideas to build a sacred, enviable harem. So he is god-like, in effect, and his women, by extension, are like goddesses. So they must live in the harem. They should be inaccessible. They should not be seen, so he’s essentially putting them on a pedestal. But he ends up confining them.

At age 52, a few years into living in the harem, Gulbadan Begum—Akbar’s aunt and chronicler—says to him, “Look, long ago, I had made a vow to go on a pilgrimage to Mecca.” And he thinks, “Okay. Wonderful, you know, my powerful aunt is going to go [to Mecca on my behalf].” The aunt is, of course, very astute. This is a formerly itinerant woman. She gathers together 11 women and they go to western Arabia. The women couldn’t be domesticated after all.

Tell me about Nur Jahan.

She was the co-sovereign along with the fourth Great Mughal of India, Jahangir. She married him in 1611 and co-ruled with him till his death in 1627. Nur ruled the vast empire along with her husband, and governed in his stead when his health failed and his attentions wandered. She was an astute politician and a devoted partner and led troops into battle to free him when he was imprisoned by one of his own officers. She signed and issued imperial orders and coins of the realm bore her name. So she’s a dazzling figure in history. I’ve tried to reinstate her with the great empresses of the world.

How did she become such an expert markswoman?

In her first marriage, which was to an ordinary Mughal officer, she went to live in the eastern provinces of India in Bengal, the land of the Bengal tiger. Nur’s husband was often away. So, that is the moment when she’d have picked up a gun. By the time she’s married to Jahangir, she’s picking up the musket pretty regularly. In all the entries I saw of his diaries, he’s obsessively writing about her hunting skills.

Jahangir had this kind of amazement at Nur Jahan’s shooting skills, especially of shooting killer tigers. This was a sovereign responsibility of only a monarch. Any Tom, Dick, or Harry was not allowed to kill a tiger. So that means Nur Jahan was acting as a sovereign, saving the lives of her subjects. When [court painter] Abul Hasan drew Nur, the portrait was unprecedented. In the picture, she was loading the musket.

Did Nur Jahan ever live in the harem?

She never lived in the royal harem. Two years into their marriage, Jahangir and Nur Jahan were on the road in these tented cities. I think it’s in this outdoor living that Nur Jahan’s co-sovereignty becomes possible. They are hunting together. Nur’s issuing imperial orders. Coins are beginning to be minted in both their names. These are all technical signs of sovereignty.

Why is the harem such a prevalent image in Mughal history, especially when there are figures such as Nur Jahan, who never lived in one?

We have these problematic pictures of Mughal history, essentially because of a sense of male disbelief. Much of Mughal history writing was male. It essentially just centered around big pictures of male figures, wars, warriors, and chieftains. The contributions of any other figures, certainly women, were completely diminished. This is the reason why we knew nothing about the harem or domestic life or indeed these very influential, very interesting female figures in history.

This has been my life’s work—to think about what is historical evidence. Who decides that evidence? Who writes a particular history? What we’re speaking about here is the politics of history-writing.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook