The Wartime Spies Who Used Knitting as an Espionage Tool

Grandma was just making a sweater. Or was she?

During World War I, a grandmother in Belgium knitted at her window, watching the passing trains. As one train chugged by, she made a bumpy stitch in the fabric with her two needles. Another passed, and she dropped a stitch from the fabric, making an intentional hole. Later, she would risk her life by handing the fabric to a soldier—a fellow spy in the Belgian resistance, working to defeat the occupying German force.

Whether women knitted codes into fabric or used stereotypes of knitting women as a cover, there’s a history between knitting and espionage. “Spies have been known to work code messages into knitting, embroidery, hooked rugs, etc,” according to the 1942 book A Guide to Codes and Signals. During wartime, where there were knitters, there were often spies; a pair of eyes, watching between the click of two needles.

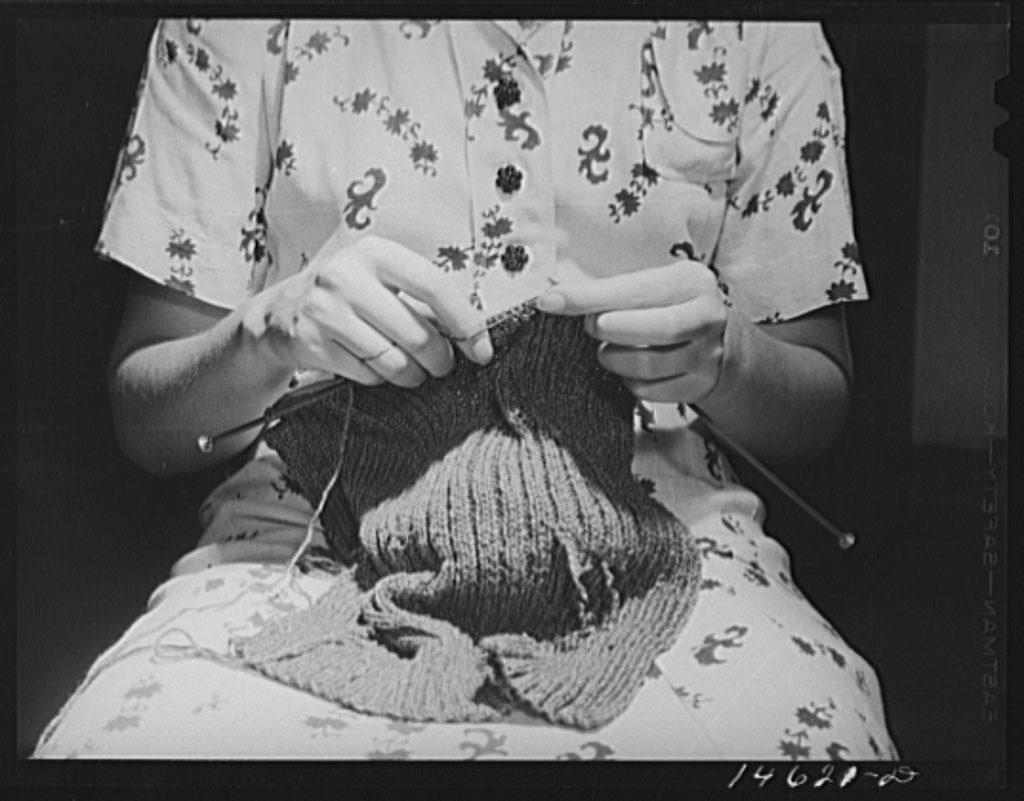

When knitters used knitting to encode messages, the message was a form of steganography, a way to hide a message physically (which includes, for example, hiding morse code somewhere on a postcard, or digitally disguising one image within another). If the message must be low-tech, knitting is great for this; every knitted garment is made of different combinations of just two stitches: a knit stitch, which is smooth and looks like a “v”, and a purl stitch, which looks like a horizontal line or a little bump. By making a specific combination of knits and purls in a predetermined pattern, spies could pass on a custom piece of fabric and read the secret message, buried in the innocent warmth of a scarf or hat.

Phyllis Latour Doyle, a secret agent for Britain during World War II—and now, at 100, the last surviving woman who spied for the Special Operations Executive—spent the war years sneaking information to the British using knitting as a cover. She parachuted into occupied Normandy in 1944 and rode stashed bicycles to troops, chatting with German soldiers under the pretense of being helpful—then, she would return to her knitting kit, in which she hid a silk yarn ready to be filled with secret knotted messages, which she would translate using Morse Code equipment.

“I always carried knitting because my codes were on a piece of silk—I had about 2000 I could use. When I used a code I would just pinprick it to indicate it had gone. I wrapped the piece of silk around a knitting needle and put it in a flat shoe lace which I used to tie my hair up,” she told New Zealand Army News in 2009. “I can remember being taken to the station and a female soldier made us take our clothes off to see if we were hiding anything. She was looking suspiciously at my hair so I just pulled my lace off and shook my head. That seemed to satisfy her. I tied my hair back up with the lace-it was a nerve-wracking moment.”

A knitting pattern, to non-knitters, may look undecipherable, and not unlike a secret code to begin with. This could cause paranoia around what knitting patterns might mean. Lucy Adlington, in her book Stitches in Time, writes about one article that appeared in UK Pearson’s Magazine in October 1918, which reported that Germans were knitting whole sweaters to send messages—perhaps an exaggeration.

“When the German authorities carefully unraveled such a sweater, the story went, they found the wool thread dotted with many knots. By marking a vertical door frame with the letters of the alphabet, spaced an inch apart, the knots could be deciphered as words by measuring the yarn along this alphabet and marking which letters the knots touched.” Adlington writes, adding that the magazine described this as “safer, and not apt to be detected.” As with many things spy-related, getting the proof and exact details on code knitting can be tricky; much of the time, knitters used needles and yarn as a cover to spy on their enemies without attracting suspicion. Knitting hidden codes was less common.

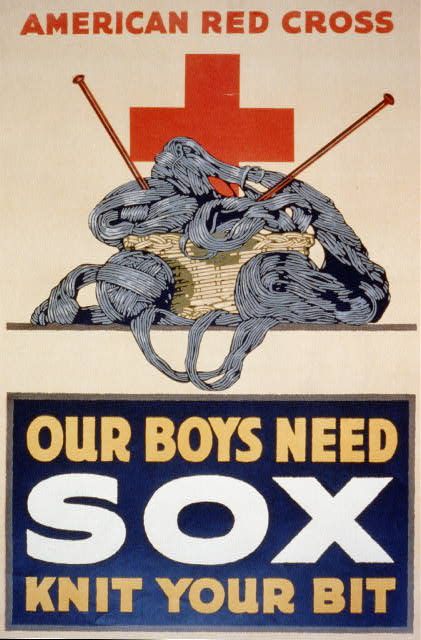

The Pearson’s account of code knitting seems a bit convoluted, but the rumors were not pure fantasy. Because women were encouraged to knit socks, hats, and balaclavas for soldiers during many conflicts, including the American Civil War, and the World Wars, knitting and textile work was a common sight—and one that could be easily used to the spy’s advantage. In Writing Secret Codes and Sending Hidden Messages, Gyles Daubeney Brandreth and Peter Stevenson note that after Morse Code was invented, it was soon realized that string or yarn suit it well. And “an ordinary loop knot can make the equivalent of a dot and a knot in the figure-eight manner will give you the equivalent of a dash.”

The most famous example of knitting in code comes from fiction; in A Tale of Two Cities, a bloodthirsty French woman named Madame Defarge knits coolly among the audience while the guillotine beheads French nobles, and zealously creates a series of stitches to encode names of nobles that will be executed next. “Despite involvement of Madame Defarge to take up knitting as a source of code, the use of knitting in espionage has nonfictional roots in the United Kingdom during the Great War,” writes Jacqueline Witkowski in the journal InVisible Culture. During the same time that the UK banned knitting patterns for fear of hidden messages, British Secret Intelligence agents hired spies in occupied areas who would pose as ordinary citizens doing ordinary things, which sometimes included knitting.

Madame Levengle was one such woman, who “would sit in front of her window knitting, while tapping signals with her heels to her children in the room below,” writes Kathryn Atwood in Women Heroes of World War I. Her kids, pretending to do schoolwork, wrote down the codes she tapped, all while a German marshal stayed in their home. The Alice Network, a collection of spies and allies in Europe who were experts in chemistry, radio, photography and more, employed “ordinary people who discovered unusual but extremely effective ways to collect information,” Atwood explains.

In many cases, just being a knitter—even if you weren’t making coded fabric—was enough of a cover to gather information, and this tradition continued decades later during World War II. Again in Belgium, the resistance hired older women near train yards to add code into their knitting, to track the travel of enemy forces. “This enactment led to the Office of Censorship’s ban on posted knitting patterns in the Second World War, in case they contained coded messages,” Witkowski writes. Knitting used by the Belgian Resistance during World War II included dropping a stitch, which forms a hole, for one sort of passing train, and purling a stitch, which forms a bump in the fabric, for another, which helped the resistance track the logistics of their enemies. Elizabeth Bently, an American who spied for the Soviet Union during World War II and later became a US informant, used her knitting bag to sneak early plans for the B-29 bombs and information on aircraft creation.

Female spies during the American Revolutionary War also used the “old women are always knitting” stereotype to their advantage. Molly “Old Mom” Rinker, a spy for George Washington during the Revolutionary War, sat on a hilltop and pretended to knit while spying on the British, according to An Encyclopedia of American Women at War. She then hid scraps of paper with sensitive information in balls of yarn, which she tossed over a cliff to hidden soldiers right below, under the noses of the enemy.

Knitting, spying and secret messages so often go hand-in-hand that knitters around the world have figured out ways you, or the knitter in your life, can make your own secret knitting codes. Non-spying knitters make gloves and scarves from the Dewey Decimal system, Morse code, and binary programming language for computers, treating knits and purls like zeros and ones. The possibilities are so apparently endless, it might even be worth learning to knit to give it a try. Plus, if you do pass on knitted code, you’ll be joining a longstanding tradition of textile-making spies.

A version of this story originally appeared on June 1, 2017. It was updated in March 2022 to include more information about Phyllis Latour Doyle.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook