Let’s Choose a New Name for ‘Indian Summer’

There are many excellent options.

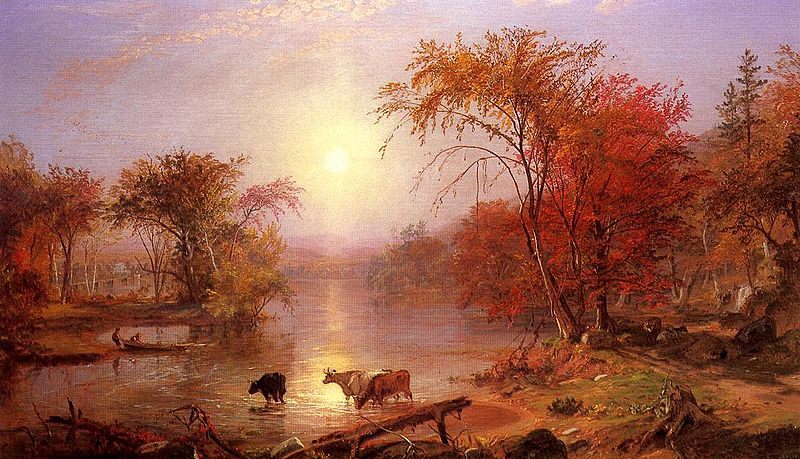

In the fall, even as trees turn red and orange, sometimes temperatures spike, from the crisp and autumnal 60s, up to a summery 80 plus degrees.* In North America, since at least the early 1800s, people have called these autumn spells of warm days and hazy skies “Indian summer.”

Think about that phrase just a little bit, and there are a few questions that come up. First, why do we call this Indian summer? Second, should we? And, if not, what else can we call it?

The undisputed authority on “Indian summer” is Albert Matthews, a Bostonian who spent 12 years in the late 19th century gathering together dozens of the earliest uses of the phrase. He searched through texts about American weather and climate going back to the 1600s; he wrote to The Dial, The Journal of American Folklore, The Nation, and other publications, asking others to send him an examples he could find; he borrowed from other dedicated searchers, until in 1902 he could say with confidence exactly when it came into common use.

The earliest use of the term that Matthews found was in the 1790s; researchers for the Dictionary of American English later discovered an earlier example, in Letters from an American Farmer. The French immigrant J. H. St. John de Crèvecoeur, who farmed in the Hudson Valley wrote that, in the fall, the severe frost “is often preceded by a short interval of smoke and mildness, called the Indian Summer.”

But the phrase didn’t become popular until at least the 1810s. “Many writers previous to 1800 neither employed the term nor recognized the season,” Matthews wrote in his extensive study, published in the Monthly Weather Review. “But by 1798 use of the term spread to New England and “to New York by 1809, to Canada by 1821, and to England by 1830.”

In his extremely thorough research, though, Matthews never discovered a convincing explanation for what the phrase meant. Why associate Native Americans with warm days in fall? There were plenty of ideas floating around: Native Americans had predicted the warm spell to settlers; they used that time of the year to extend their harvest; a tribe’s mythology connects the weather to the sigh of the personified southern wind. “Indian summer” may have had a tinge of colonial nostalgia to it, too. Some of the examples Matthews found argued that by the 1800s “Indian summer” had disappeared. “This short season of mild and serene weather, the halcyon period of autumn, has disappeared with the primitive rest,” wrote one 19th century author. “It fled from our land before the progress of civilization; it has departed with the primitive forest.”

As the current high temperatures show, the weather that characterizes “Indian summer” has definitely not disappeared. But that quote offers a hint that the phrase’s growing popularity could have been connected to the absence of native people, rather than any real native practices. Matthews (rightly) dismisses all of the explanations he found as “vague and uncertain.”

So, after 200 years, we may want to use a term with less colonial overtones. There are many other options of what to call these late-breaking days of autumn warmth.

In Europe, streaks of warmth in autumn are often named after saints whose feasts fall around this time: This one could very accurately be called by a British name, St. Luke’s summer—the saint’s feast day is on October 18. Other countries associate these warm spells with other saints. In Finland, there’s Pärttylin pikkukesä, associated with Pärttylin, Saint Bartholemew. In Spain, there’s Veranillo de San Miguel or Veranillo de los Arcángeles, the little summer of St. Michael or of the Archangels, San Miguel, San Rafael and San Gabriel. Earlier in October, Bridget of Sweden has her feast day, and Swedes sometimes call warm spells brittsommar. In France, there’s also l’été de la Saint-Denis, and in Britain and other countries, All Saints’ or All Halloween summer, if it falls around Nov. 1.

In many European countries, a November warm spell is called St. Martin’s summer—his feast day in November 11th.

But the possibilities do not end there. In Germany, the Netherlands and Eastern Europe, warm autumn streaks are called “old wives’ summer”—it’s Altweibersommer in German, oudewijvenzomer in Dutch, babie lato in Polish, babí léto in Czech, babje ljeto in Russian and so on. Many European countries also have names for this phenomenon which are connected to nature. Spain can have a veranillo del membrillo, a quince summer, because it’s around this time of year that quince finishes its ripening. Sweden can have a grävlingssommar, a “badger summer,” when badgers have one last chance to replenish their stocks for the winter. In Brittany, they call this “the summer of ferns,” which have turned colors already, and in Dutch the kranenzomer, or crane summer.

The word “gossamer” is also associated with late autumn warmth—it either comes from “goose summer” or “go-summer,” a Scottish word that plays on the passing of summer, and is associated with the glossy spider webs that can be found in the fields of this season. Sometimes those webs are also connected to the “old wives’ summer”—they’re supposed to be reminiscent of old women’s hair. In Turkey, they call this time of year “pastirma summer” because the mild weather of early November is perfect for making the cured, salted meat called pastirma (which gave pastrami its name but is its own delicious thing).

Or there are simpler options. Latvians calls this atvasara, and the Dutch also use nazomer, both of which mean “late summer.” In English, before Indian summer came into vogue, sometimes we called this “second summer.” There’s a strong case to be made for badger summer, pastrami summer, or quince summer as an alternate name for Indian summer, but perhaps simple is best. Enjoy these second summer days, before the frost of fall really sets in.

*This sentence has been updated from the original post.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook