Lovely Hidden Paintings Adorned the Edges of Historic Books

Fore-edge paintings. Just look at them!

While you don’t see them very often these days, fore-edge paintings were once some of the loveliest book illustrations around. Literally, they were around the edges of the book.

A fore-edge painting refers to an image painted or drawn on the closed leaves of a book. While covering the collected page edges in gold or silver leaf was a popular choice, sometimes artists went one step further and painted whole scenes and landscapes on them. This form of fore-edge decoration is known as “all-edge” painting, and it was only the beginning.

Some ambitious, “disappearing” fore-edge paintings were painted on the inside edges of the pages, so that the hidden scenes could only be seen when the page block was fanned in a certain direction. If the book was simply closed, the page edges could look normal and unadorned (or possibly gilded), only revealing the image when one of the covers were shifted back, slanting the pages.

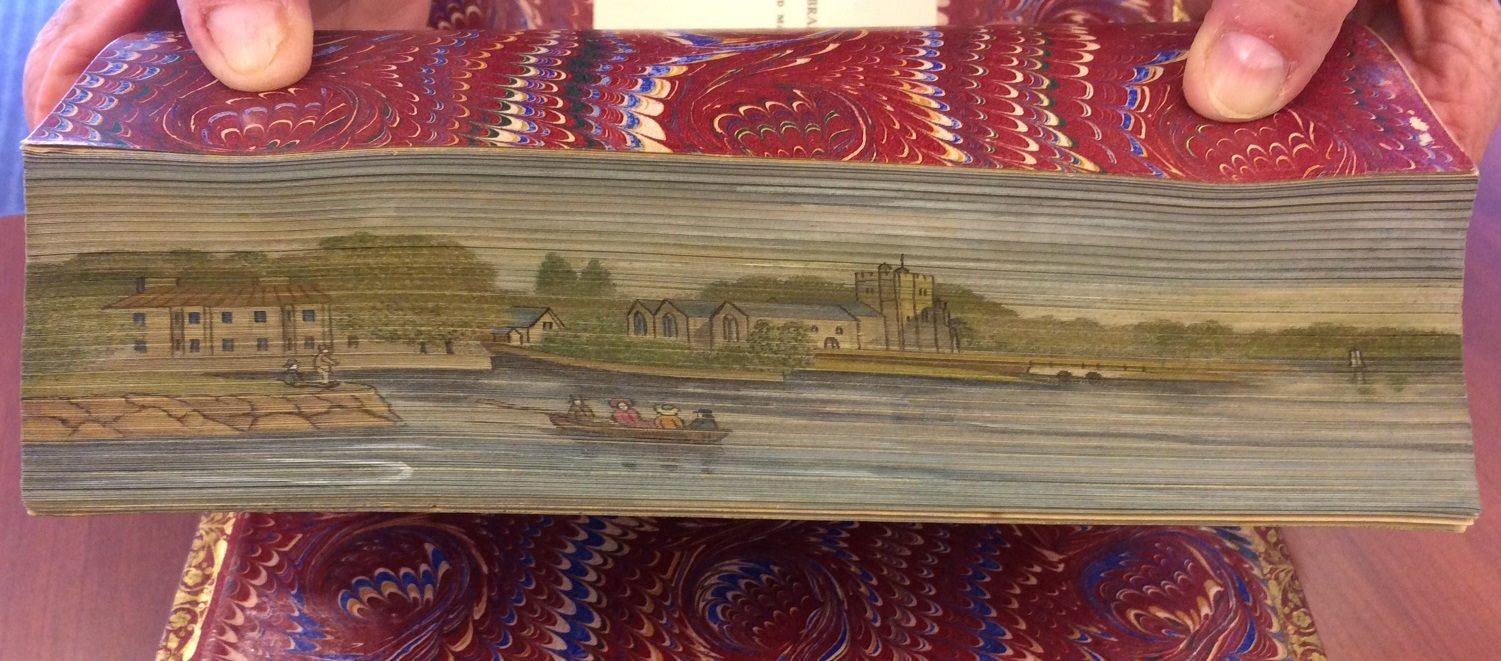

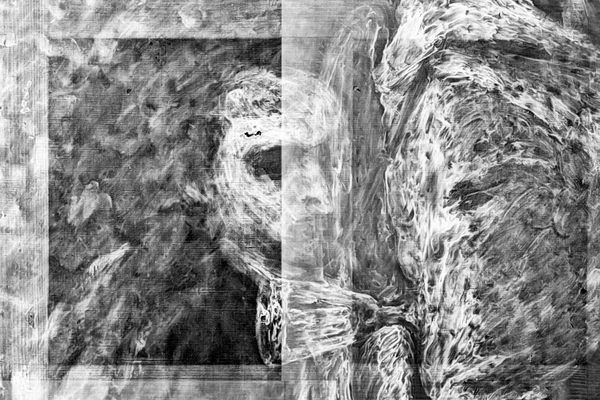

A two-way double fore-edge painting from The Book of The Thames (1859), slanted one way… (Photo: Courtesy of The Swem Library)

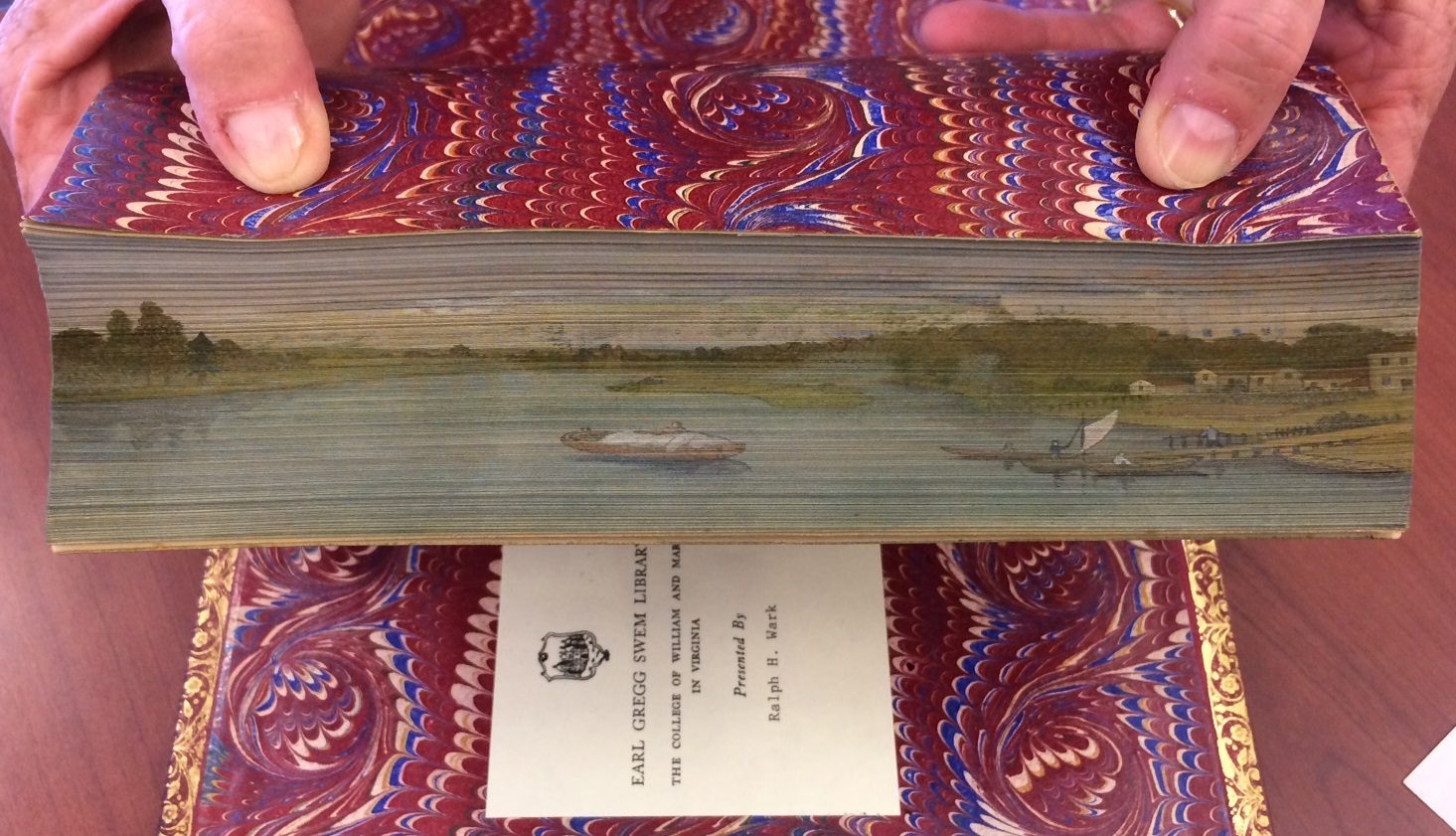

… and the other.(Photo: Courtesy of The Swem Library)

These secret illustrations could be doubled, with an illustration on either side of the pages, revealing themselves depending on the slant of the page block (known as the “two-way double”). Some were painted so that if the book was laid open in the center, naturally splaying the pages to either side, two different illustrations could be seen on either side (known as a “split double”).

There are even examples of rarer variations that required the pages to be pinched or tented in a certain way to see the image. The only limit was the artists’ imaginations.

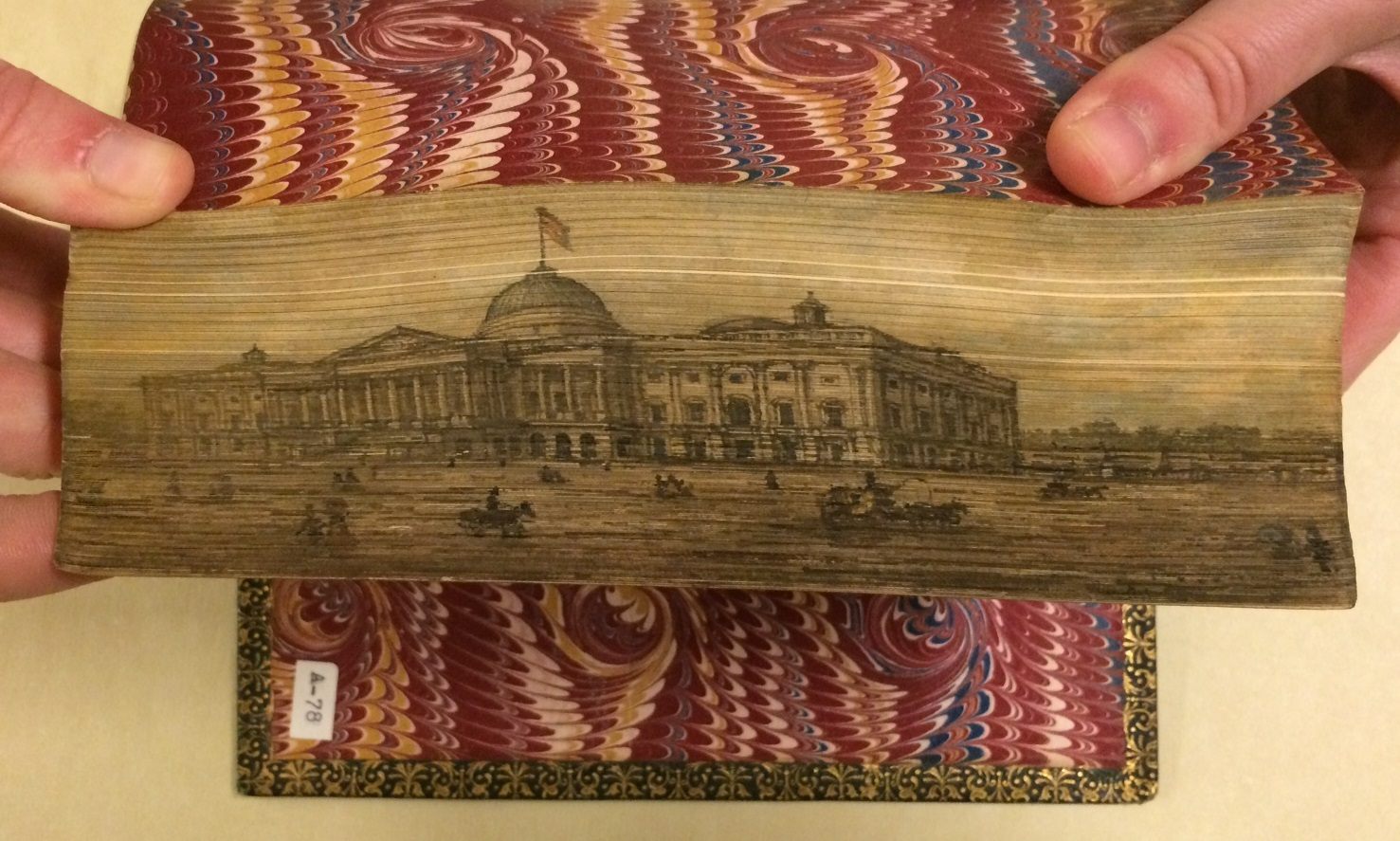

The American capital painted on the edge of American Poems (1870). (Photo: Courtesy of The Swem Library)

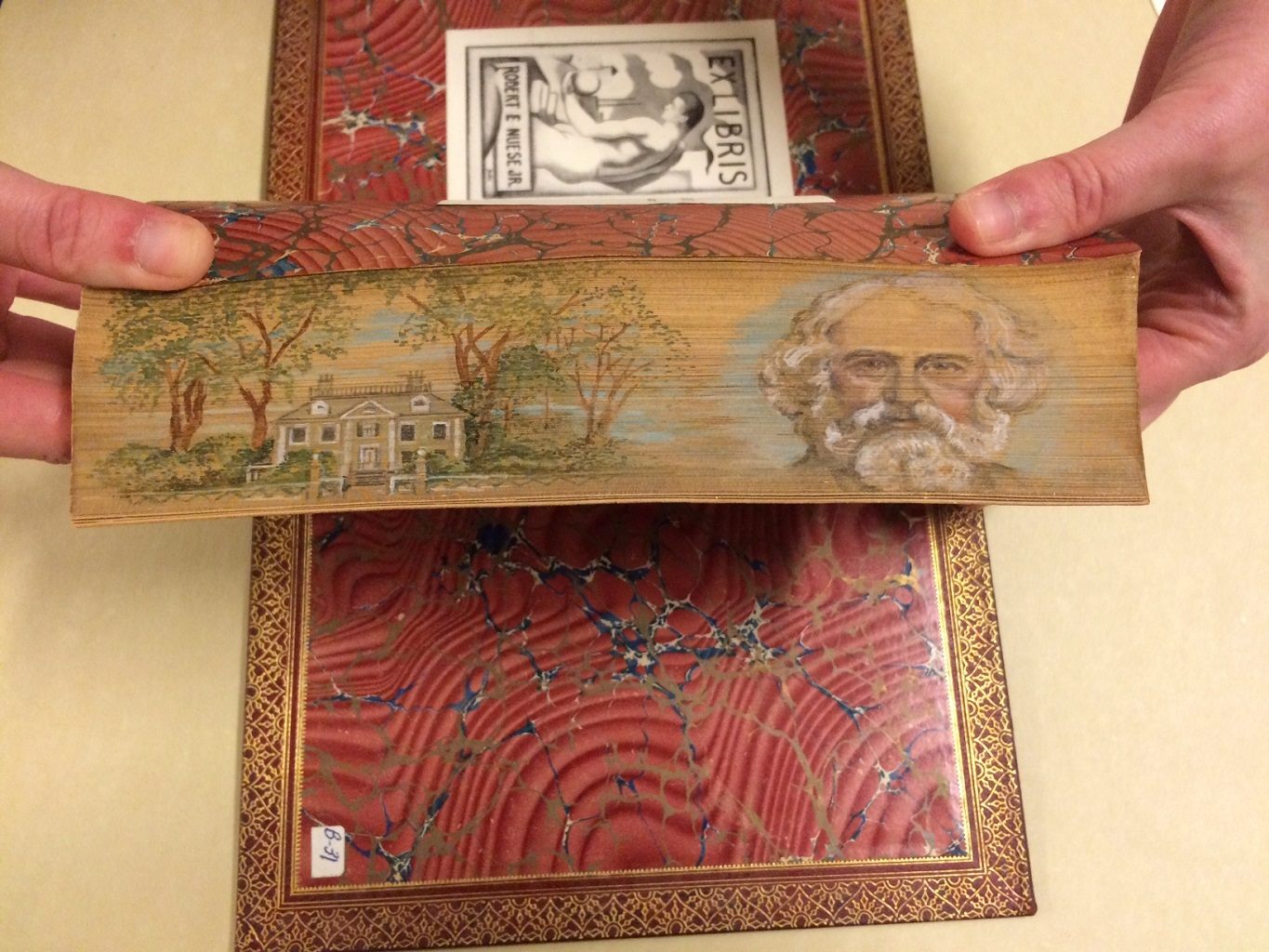

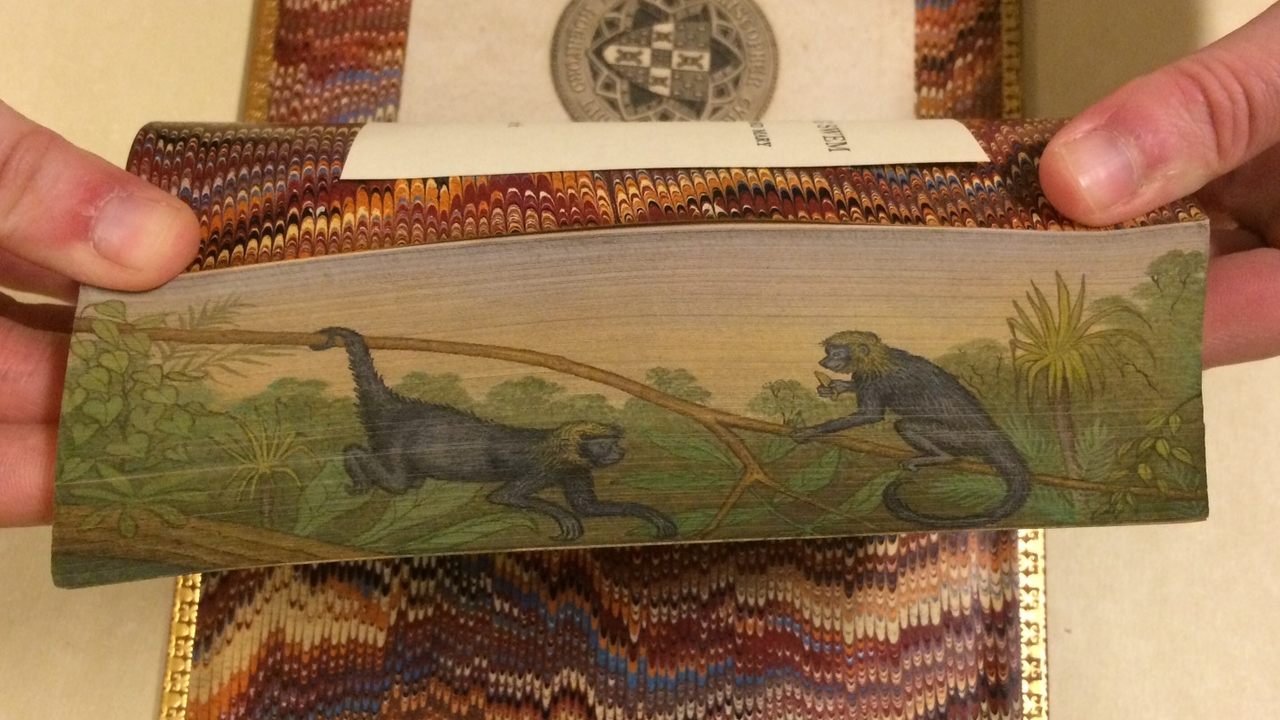

“Sometimes the fore-edge paintings corresponded to the subject of the book, and sometimes not,” says Jay Gaidmore, Director of Special Collections at the Earl Gregg Swem Library. The library holds the 700-strong Ralph H. Wark Collection, the largest collection of fore-edge painted books in America.

“Typical scenes include Oxford and Cambridge, the Thames River, Westminster Abbey, the English village and countryside, Edinburgh, authors, ships, and classical figures,” says Gaidmore. “Most of the books are 19th century English fore-edges, but there are a few American scenes.”

Henry Longfellow from The Complete Poetical Works of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. (Photo: Courtesy of The Swem Library)

Fore-edge paintings can be found on books dating back to the 11th century, with early examples being decorated with symbolism and heraldry. Disappearing fore-edge paintings began to appear around the 17th century, as the paintings began to become more elaborate, consisting of fully illustrated scenes, portraits, and composed artworks.

It wasn’t until many centuries later that the art form had a Renaissance, and become more common. “Fore-edge paintings peaked in the late 18th and early 19th centuries in England,” says Gaidmore. ”Edwards of Halifax, part of the Yorkshire family of bookbinders and booksellers, has been credited with establishing the custom.”

According to the Boston Public Library’s website for their 250+ collection of fore-edge books, for the most part the paintings were made using watercolors, and went unsigned, often being commissioned by a book-binding firm.

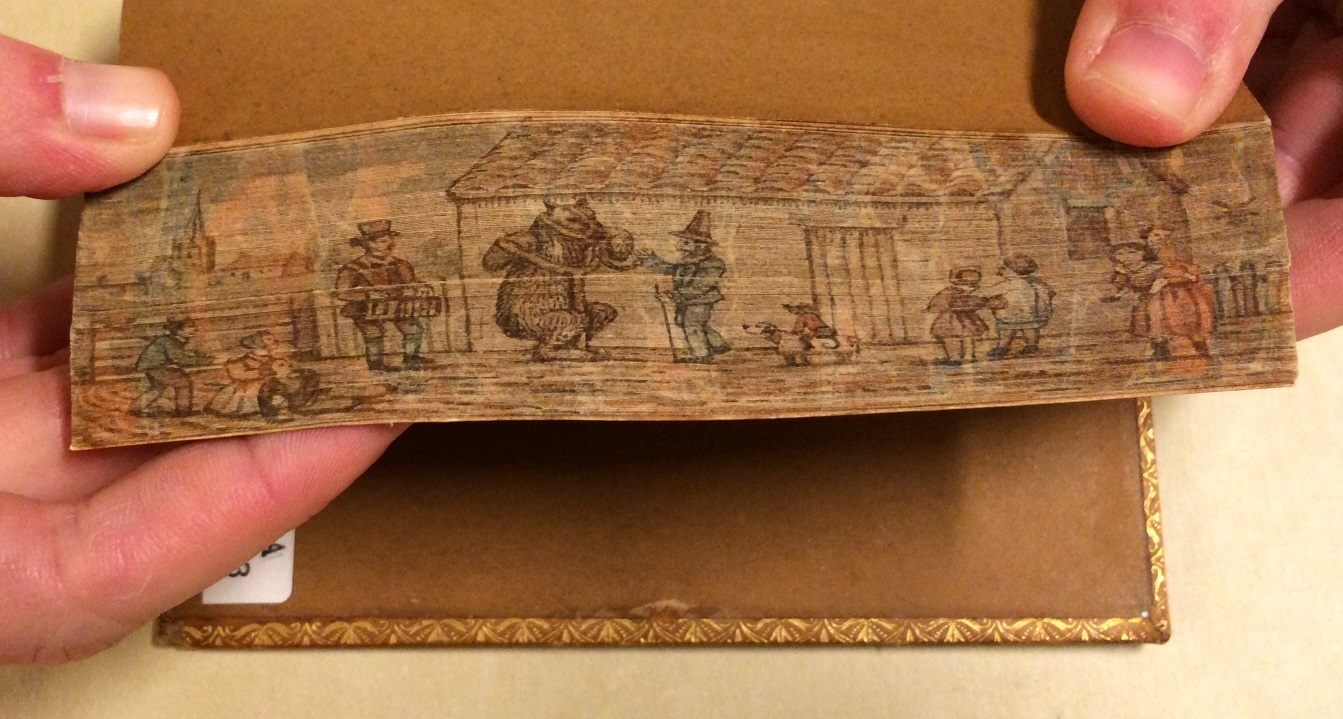

A circus scene from Essays, Poems, and Plays (1820).(Photo: Courtesy of The Swem Library)

Examples of fore-edge painting continued into the early 20th century, and as a 2013 piece over on Flavorwire points out, they are still being created by modern artists such as Clare Brooksbank and Martin Frost.

The technique has even been printed onto some modern books like Chip Kidd’s 2001 novel, The Cheese Monkeys, which was printed with a two-way double, disappearing fore-edge message. If the pages are shifted in one direction, the phrase “GOOD IS DEAD,” appears, while if they are shifted in the opposite direction, the message, “DO YOU SEE?” can be read.

Take a look at more incredible historical fore-edge paintings below.

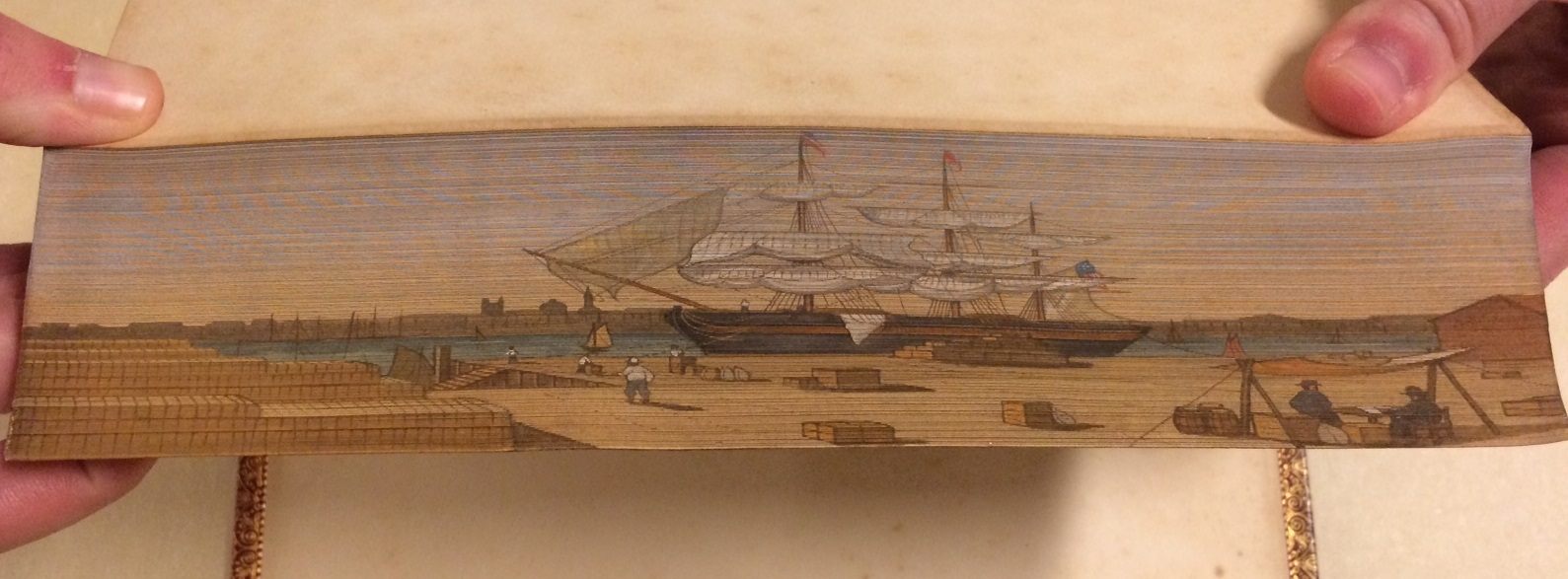

A ship painted in Lectures on Modern History (1843).(Photo: Courtesy of The Swem Library)

A tiny farm scene on the side of The Farmer’s Boy (1827). (Photo: Courtesy of The Swem Library)

John Milton’s house, grave, and portrait on the side of Paradise Lost, Vol. 1. (1796). (Photo: Albert H. Wiggin Collection/Boston Public Library)

Matches, Mackerel, Scissors on the side of The Poems of William Cowper (1820). (Photo: Albert H. Wiggin Collection/Boston Public Library)

The Last Supper on the edge of The Holy Bible (1803). (Photo: Albert H. Wiggin Collection/Boston Public Library)

A hunter firing at a bird on the side of The Poetical Works of John Milton (1843). (Photo: Albert H. Wiggin Collection/Boston Public Library)

A hunt on the side of The Seasons (1811). (Photo: Albert H. Wiggin Collection/Boston Public Library)

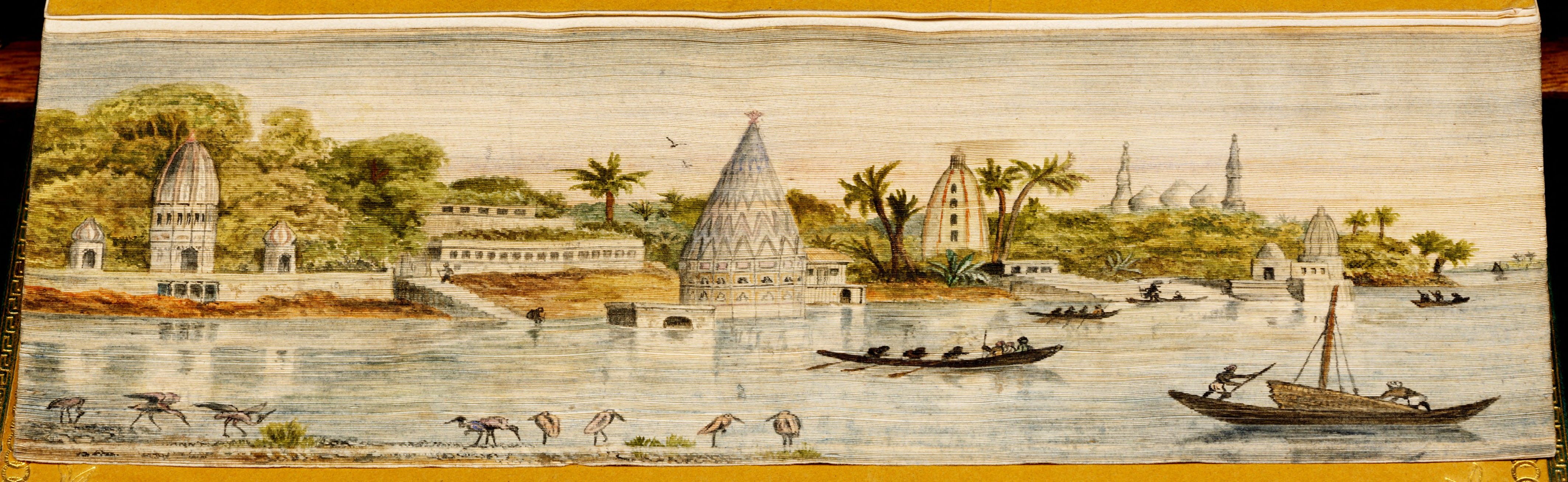

Hindu temples painted on the side of The Modern History of Hindostan. Volume 1 (Date unknown). (Photo: Albert H. Wiggin Collection/Boston Public Library)

Four putti on the edge of Des. Erasmi Rot. Moriæ encomium (1629). (Photo: Albert H. Wiggin Collection/Boston Public Library)

Diana sitting with a handmaid by a lake from the side of Dictionnaire Grec-Français (1817). (Photo: Albert H. Wiggin Collection/Boston Public Library)

Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden on side of The Bible (1795). (Photo: Albert H. Wiggin Collection/Boston Public Library)

Aylesford Church and bridge on the side of Sermons, Vol. 2 (1814). (Photo: Albert H. Wiggin Collection/Boston Public Library)

A chess scene from the side of Analysis of The Game of Chess (1790). (Photo: Albert H. Wiggin Collection/Boston Public Library)

The people of Orleans greet Joan of Arc, from the side of Jeanne d’Arc: Her Life and Death (Date unknown). (Photo: Albert H. Wiggin Collection/Boston Public Library)

George Washington and Ben Franklin from the side of The Speeches of The Right Honourable William Pitt (1808). (Photo: Albert H. Wiggin Collection/Boston Public Library)

Stonehenge painted on the side of The Royal Kalendar, and court and City Register for England, Scotland, Ireland, and The Colonies (Date unknown). (Photo: Albert H. Wiggin Collection/Boston Public Library)

The White House painted on the edge of A History of New York (1821). (Photo: Albert H. Wiggin Collection/Boston Public Library)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook