Manhattan Was Almost Home to a 200-Foot-Tall Owl Mausoleum

Newspaper publisher James Gordon Bennett Jr. was obsessed with owls. Sculptor Greg Lefevre created a bronze owl sculpture for him in Herald Square. (Photo: Laura/flickr)

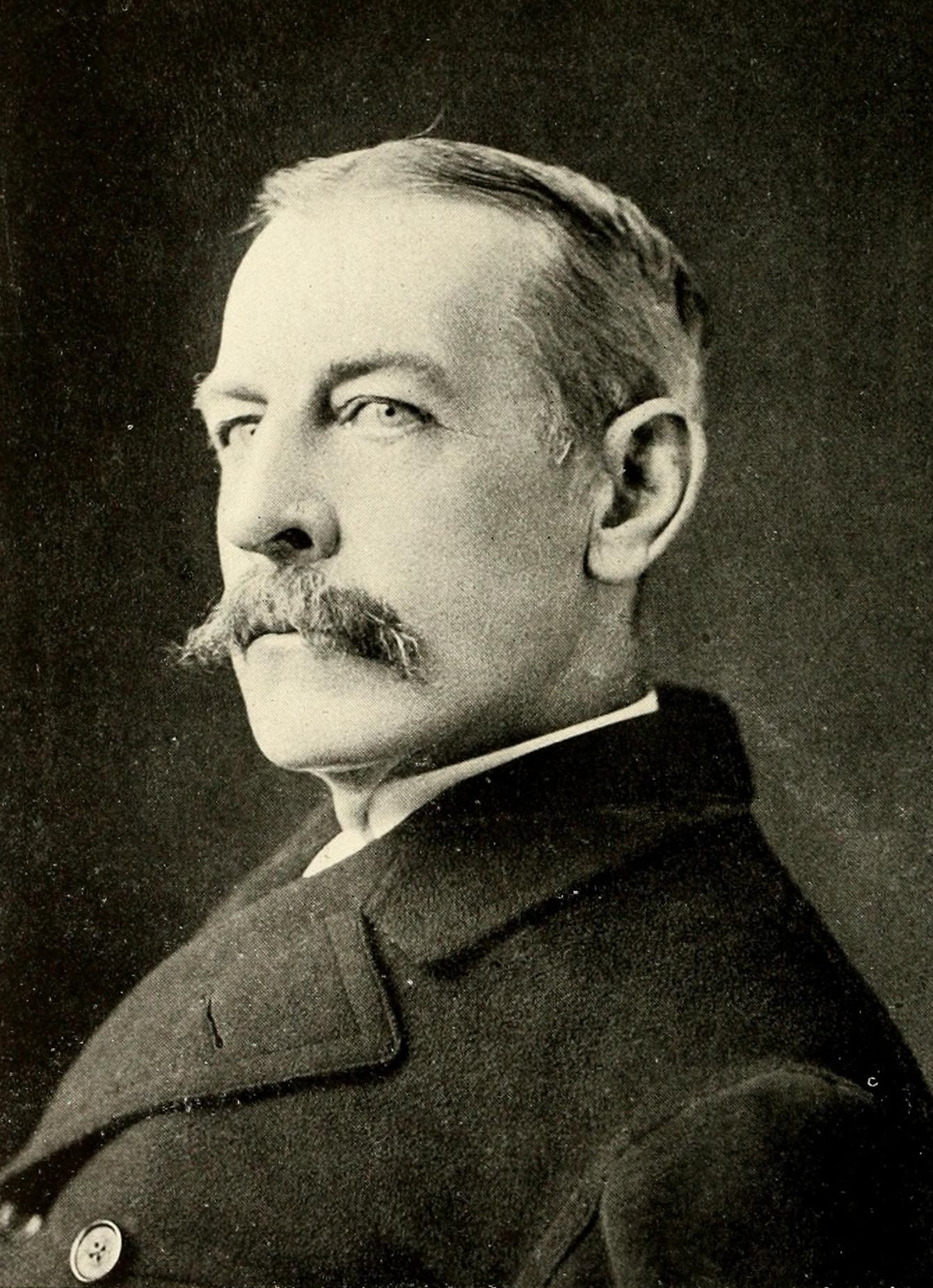

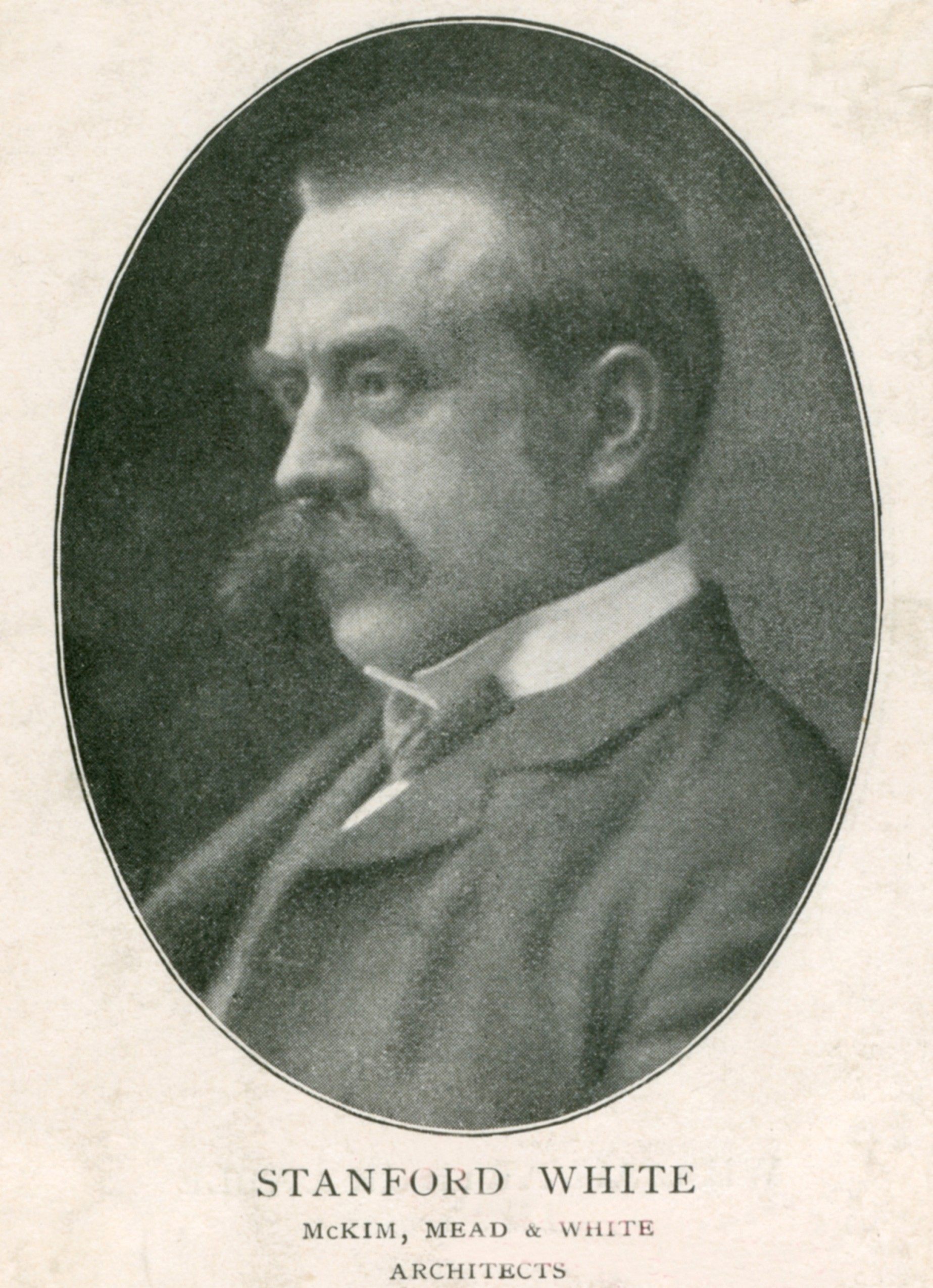

In 1906, one of New York’s premier architects, Stanford White, received an unusual commission. The request came from his friend James Gordon Bennett Jr., the publisher of one of America’s most circulated daily newspapers, the New York Herald.

The media tycoon asked White to design and build his tomb. But this was to be no ordinary mausoleum. Bennett Jr. had something fantastic in mind for his final resting place: a sarcophagus soaring 200 feet into the New York skyline in the form of an owl. Furthermore, Bennett wanted the owl to be hollow, and for his coffin to be suspended midway inside the owl’s body by iron chains.

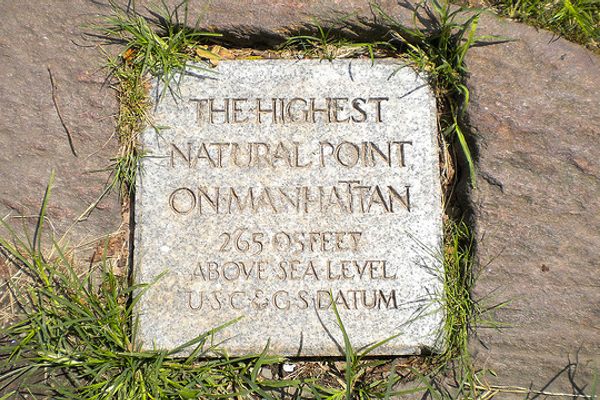

This enormous owl mausoleum was to be situated in Washington Heights, on a plot of land owned by the Bennett family. Still there today on 183rd Street, the area now known as Bennett Park comprises the highest point of land in Manhattan, 265 feet above sea level.

Bennett’s instructions for White specifically called for a 75-foot pedestal, where an 125-foot owl would rest. This was no sealed-off gravesite, though. The monument was intended to be open to the public. The New York Times reported on the proposed design: “Through the interior of the tomb, a circular staircase was to ascend from the bottom of the pedestal, around the coffin and the great iron chains, up to the eyes of the owl, which were to be windows looking over New York City.”

The top of the owl would have been 465 feet above sea level. To put that size in perspective, the Statue of Liberty is 305 feet tall. For Stanford White, and his illustrious architecture firm of McKim, Mead & White, it was a far cry from previous projects like Columbia University, the Brooklyn Museum, and the second Madison Square Garden (and later ones like Pennsylvania Station and the New York Public Library).

An illustration of the plans, believed to have been drawn by Andrew O’Connor.

An illustration of the plans, believed to have been drawn by Andrew O’Connor.

It all begs the question: What sort of man would chose to immortalize himself with a 200-foot owl?

James Gordon Bennett Jr. was widely known in New York society as an eccentric playboy. He inherited the New York Herald from his father, James Gordon Bennett Sr., in 1867. The Scotland-born elder Bennett had emigrated to North America at the age of 24. After working as a school teacher and freelance reporter, he founded his own newspaper in 1835. The sensationalistic New York Herald would go on to become one of the most successful “penny papers” in America.

Operating under the ethos that the function of a newspaper “is not to instruct but to startle,” the Herald specialized in crime, scandal, and political attacks. The more salacious the better; the year after debuting, the paper hit the sales jackpot thanks to its obsessive coverage of the murder of a high-class prostitute. By the time Bennett Sr. handed over control of the newspaper to his son, it reportedly had the highest circulation of any newspaper in America.

At the time, Gordon Jr. was one of the richest bachelors in the city. He led a life of excess, eccentricity and general caddishness. Known in Manhattan clubland as the Commodore, he scandalized New York society with his erratic behavior. He was known for spending late nights racing his horse drawn carriage in the nude. Engaged to socialite Caroline May, the arrangement was said to have been broken off after he arrived at the May family mansion, wildly intoxicated, and urinated into the grand fireplace.

Fleeing to France, he lived for a time on Louis XIV’s estate at Versailles. From here he built a 301-foot yacht called the Lysistrata. With a permanent crew of 100 ready to sail at the owner’s instant whim, the yacht came complete with it’s own padded stall and a cow to deliver fresh cream to the captain’s table. It also carried a French sports car.

James Gordon Bennett Jr. in 1901. (Photo: Wikipedia Commons)

Overseeing the running of the Herald from France, Bennett Jr. brought the same largesse to the paper. He sponsored a reporting trip to Africa to track down the missing missionary David Livingstone. While it was the journalist Henry Morton Stanley who uttered the famous line, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume,” it was Bennett and the Herald that paid the bills.

In the 1890s Bennett decided to leave “Newspaper Row” in lower Manhattan, and head uptown. His paper would no longer be next door to fierce competitors like Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal, and Henry Jarvis Raymond’s New York Daily Times. Bennett asked Stanford White to design the new home of the New York Herald, on a large plot in Midtown now called Herald Square.

Naturally, Bennett Jr. gave White specific instructions on how his sumptuous new headquarters was to be decorated, with a theme that reflected his unwavering obsession with owls.

White’s Herald building had an exquisite design, based upon the Italian renaissance-era Palazzo del Consiglio in Verona—but with a twist. The roofline of the building was festooned with bronze owls, no less than 22 of them. The owls positioned on the corner of the Herald had bright green glass eyes lit up by incandescent bulbs.

Minerva, the typesetters, and a trusty owl atop the bell. (Photo: Luke J. Spencer)

A large bronze statue of Minerva dominated the front of the building, alongside a pair of bronze typesetters, who mechanically rang a bell with heavy mallets. The Roman goddess was shown with an attendant owl, perched atop the bell. Bennett also took to keeping live owls in the office, wearing owls on his cufflinks, and painting owls’ eyes on the prow of his beloved Lysistrata yacht. Soon, the masthead of the Herald itself featured an owl.

What lay behind Bennett’s obsession with owls? The owl has traditionally been a symbol of wisdom and intelligence, dating back to the Greek goddess Athena, whose temple in Athens, the Acropolis, was home to a protected group of owls. The creature has also had a long association with secret societies. The Order of the Illuminati’s Minerval Academy is said to have used an owl perched upon an open book as its seal.

During Bennett’s time, Manhattan was home to a mysterious member’s club for journalists called the Bohemian Club. Its symbol depicted an owl and the words “Weaving Spiders Come Not Here.” The association, whose members included powerful figures like William Randolph Hearst, owned 2,700 acres of land in the California Redwoods, where a 40-foot stone owl statue stood sentry over the main gathering area. Annual two-week retreats there began in 1878, and still continue today. Bennett was possibly a member of this club, but evidence is scant.

Perhaps he just really loved hoot owls, plain and simple. Indeed, he ran numerous editorials in his paper fighting for the preservation of the species.

Stanford White. (Photo: Everett Historical/shutterstock.com)

Bennett’s grandiose plan for a 200-foot-tall owl tomb in Washington Heights came to an abrupt end on the night of June 25th, 1906. Architect Stanford White was murdered while attending a performance of “Mam’zelle Champagne” on the rooftop theatre of the old Madison Square Garden.

White’s philandering and sexual assaults had finally caught up with him: During the show’s musical finale, a song called, “I Could Love a Million Girls,” the husband of one of his most infamous lovers gunned the architect down, and reportedly shouted either “you’ve ruined my wife” or “life.”

Before White was shot in the head, plans for Bennett’s giant owl tomb had been moving right along. White had already hired a sculptor in Paxton, Massachusetts to work on the designs. Artist Andrew O’Connor had gotten as far as pencil sketches and clay models of the outlandish tomb. But the plans were permanently shelved once Bennett heard of White’s murder, sadly depriving New York City of the chance to host an enormous owl-shaped mausoleum with a coffin swinging from chains inside it.

The New York Herald building, circa 1895. (Photo: Library of Congress)

James Gordon Bennett Jr died in 1918, and three years later his owl-themed Herald Building was demolished. Despite the expense put into the building, Bennett had only signed a thirty-year lease. Asked once why the lease was so short, he reportedly said, “Thirty years from now the Herald will be in Harlem, and I’ll be in hell!”

The New York Herald ceased publication in 1924. Yet remnants of what had been America’s most widely read newspaper can still be found: its former Parisian edition lives on today as the International New York Times, and the statue of Minerva and her bell-ringing typesetters, which decorated the façade of the lost Herald Building, was preserved and turned into the clock tower seen in today’s Herald Square. Behind the clock tower is a door, featuring an owl perched upon a crescent moon, and a phrase in French, la nuit porte conseil, which translates to “sleep on it.”

Atop the monument are two of the original 22 owls that adorned the roof of James Gordon Bennett Jr.’s newspaper building. Their eyes silently flicker on and off with a mysterious green light, going all but unnoticed by the thousands of passersby below.

The James Gordon Bennett Memorial, in Herald Square. (Photo: Luke J. Spencer)

The memorial at night. (Photo: Luke J. Spencer)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook