Martha Matilda Harper, the Greatest Businesswoman You’ve Never Heard Of

She pioneered retail franchising and created the American hair salon industry.

Nearly 30 years before Helena Rubenstein and Elizabeth Arden launched their beauty brands, a former servant girl from Canada created the American hair salon industry, designed the first reclining salon chair, and went on to establish retail franchising as we know it today. Along the way she empowered thousands of young women and amassed a fortune.

Martha Matilda Harper was born in 1857 into a working class family in Ontario, Canada. At the age of seven, her father bound her out in servitude to an uncle, and she was sent 60 miles from home to begin a life of drudgery. Eventually, she went to work for a German holistic doctor, who taught her his revolutionary ideas about hair care. Harper learned about stimulating blood flow to the scalp through vigorous hair brushing, and the importance of hygiene; all new ideas at the time. She embraced the doctor’s practices and her own hair flourished. Before he died in 1881, the doctor gave Harper his secret hair tonic formula, little knowing the effects his small bequeath would have on Harper and American society.

The next year Harper immigrated to Rochester, New York, once again as a servant, but she had the tonic and a plan.

“At the end of the 19th century, Rochester was a hot bed of innovation. If you were slightly weird you fit in, so it was the perfect community for someone who was daring to introduce a new concept,” says Jane Plitt, author of Martha Matilda Harper and the American Dream: How One Woman Changed the Face of Modern Business.

Soon Harper was delighting her new employer, Luella Roberts, and Roberts’ affluent friends with her hair skills and secret tonic (an organic shampoo). During the Victorian era, people either didn’t wash their hair, or used harsh soaps. Women had their hair done at home by servants, or independent hairdressers, but Harper had the revolutionary idea of opening a public hair salon for women.

In the midst of planning her new venture, Harper got very ill, and was nursed back to health by a Christian Science healer. The experience turned her into a lifelong Christian Scientist, and the church’s teachings and organization would have a profound effect on Harper’s business.

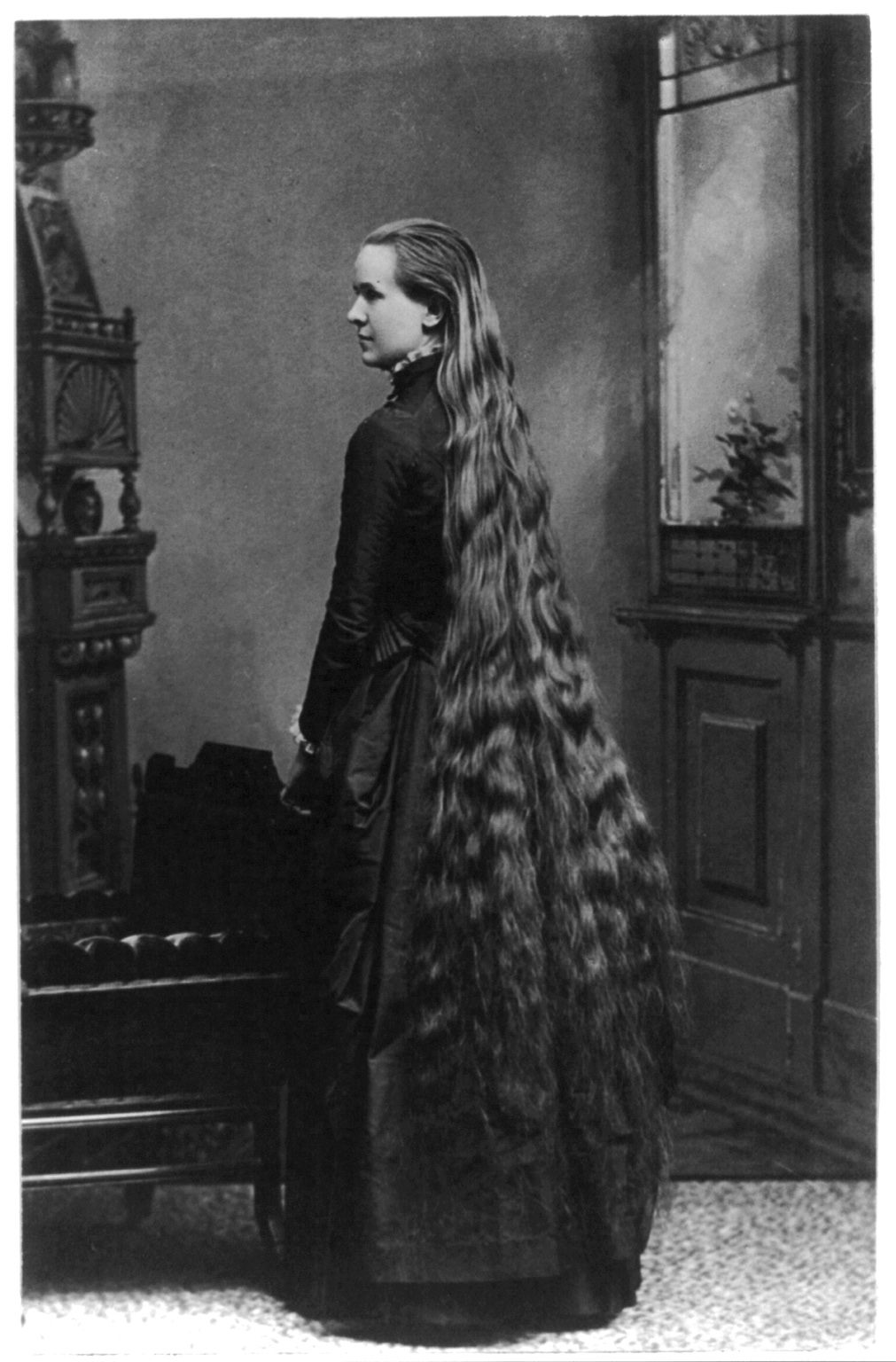

In 1888 Harper used her life savings of $360 to open her first salon. That same year, George Eastman launched Kodak in Rochester with $1 million in venture capital. Convincing women to have their hair done in public would be a tough sell, so Harper chose the location of her salon strategically. She used connections through Roberts to secure space in the prominent Powers Building in downtown Rochester, and placed a large photograph of herself showcasing her floor-length hair on the door.

The customers did not come, so Harper employed a brilliant marketing tactic. Next door to her fledgling salon was a children’s music school, which lacked a waiting room. Every day well-heeled mothers would bring their children to class, only to be left standing in the hall. Harper invited the women to rest in her salon, and lured them into trying her services; what would become known as the Harper Method.

After nearly a quarter century in servitude, Harper knew how to pamper her clientele. She designed the first reclining chair so they could have their hair washed without getting shampoo in their eyes, and had a half circle cut out of her sink (with running water) for ladies to rest their heads. The emphasis was on customer service, long before the term was coined. Once women experienced the Harper Method, they were converts.

Her clients were made up of an unlikely blend of society ladies and suffragists, whose movement was spearheaded in Rochester. Soon Harper was catering to both circles, and women in each sphere were spreading the word about the new salon. Susan B. Anthony was a friend and client.

“What was significant was it was a combination of the hoi polloi ladies who came as customers along with the suffragettes who helped network the business,” says Plitt. “Alexander Graham Bell’s wife Mabel became a client, and she brought Grace Coolidge, the future First Lady, and Grace brought [socialite and social activist] Bertha Honoré Palmer. It was women’s networking at its best.”

Palmer became such a fan that she insisted Harper open a shop in her native Chicago in time for the world’s fair of 1893. Harper shrewdly replied that Palmer needed to get a commitment from twenty-five women to patronize a Chicago shop.

With the commitment secured, Harper had to figure out how to expand her business with her limited resources. According to Plitt, she looked to the Christian Science Church for guidance. Under the strict direction of founder Mary Baker Eddy, the church maintained satellite operations throughout the country. Harper decided this was the model she would replicate.

She also incorporated the goal of the suffragists to empower women. In particular, Susan B. Anthony advocated women having financial independence in an era when women had very few rights, least of all financial.

“She used the model to enable other poor servant girls and factory girls to transform their lives,” Plitt says.

By dictating that poor women would open the first 100 salons, in one fell swoop Harper became a pioneer of social entrepreneurship and modern franchising. (The word franchising comes from the French, and literally means “to free from servitude”.) Ray Kroc of McDonald’s is widely credited with being the father of American franchising, but Harper beat him to it by 60 years.

The first two franchises were opened in 1891 in Buffalo and Detroit. Franchisees had to purchase Harper’s chair and sink (which she unfortunately did not patent) and all of her products. Because the women—who became known as “Harperites”—usually lacked the funds for the upfront costs, Harper loaned them the money to buy the franchise.

In 1893 Harper opened her Chicago salon in time for the fair, and she continued to expand; eventually having over 500 shops globally, including outlets throughout the United States*, a network of beauty schools training women in the Harper Method, and a factory in Rochester to manufacture her organic products. As her empire grew, the rich and famous flocked to her shops.

Harper’s loyal clients included members of the British royal family, the German Kaiser, the actress Helen Hayes, and Rose and Joseph Kennedy (and later, Jacqueline Kennedy and Lady-Bird Johnson). While negotiating the Treaty of Versailles, President Woodrow Wilson traveled to Paris nightly to the Harper salon to have his scalp massaged. Hair treatments for men—including massage—were a novelty, and one of Harper’s many innovations.

Sally Knapp, 81, is one woman whose life was changed by Harper. She entered Harper’s beauty school in Rochester right out of high school.

“I was a Harper girl, and graduated in 1954,” Knapp says. “At the time beauty schools did not have the best reputation. They seemed dirty to me, and Harper was different, the approach was different. It was on hair care rather than simply coiffing.”

In 1957, Knapp took over a Harper salon in Baltimore, and ran the business for 50 years.

“She gave me my career and I think she gave me some principles of how you treat people. The idea of caring for people came from my training, and that definitely came from Martha,” Knapp says.

Harper never lost sight of her original goal of empowering women. Her salons offered childcare and were open in the evening to accommodate busy women’s schedules. Unlike John Rockefeller, who lived in a fortress, Harper’s Rochester mansion was open to all “Harperites” when they came to town.

She refused to marry until she was fully in control of her empire, and at the age of 63 married Robert MacBain, who was 39.

She stepped down as CEO in 1932 and MacBain took over. He began to transform the company, introducing chemical dyes and permanents (which were forbidden under Harper, who strictly used natural products) and the female “esprit de corps” was gone, according to Plitt. Harper died in 1950 at the age of 92, and by the time MacBain sold the company in the 1970s, it was a shadow of its former self. The last Harper salon closed in Rochester in 2005.

The woman who transformed the lives of so many, and changed the face of American business never got her due in life. While the remaining “Harperites” are fiercely loyal, Harper’s is a name largely forgotten.

“She’s important as a national business figure,” says Sarah LeCount, Collections Manager at the Rochester Museum & Science Center, which has a large collection of Harper artifacts, including two of her shampoo chairs.

“She really felt that by developing her salon system she was helping women establish a financial life of their own beyond their husband’s, or allowed them to live without a husband.”

In 2001 Harper was posthumously honored with an award from the International Franchising Association; and was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2003.

“She is lost in history and I think it’s too bad,” says Knapp. “It happens and makes you wonder about your worth sometimes in life. Martha stood for a lot of things and it’s a shame that it’s been lost in the history pages.”

*CORRECTION: The story originally said that Harper had stores in all 50 American states. There weren’t 50 states yet established during her lifetime.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook