The Strange and Grotesque Doodles in the Margins of Medieval Books

When the edges take center stage.

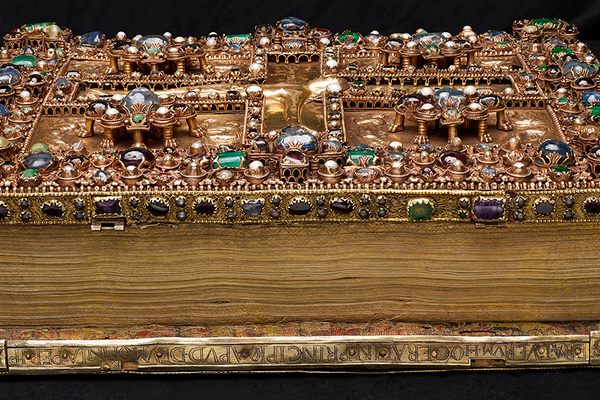

Manuscripts can be seen as time capsules,” says Johanna Green, Lecturer in Book History and Digital Humanities at the University of Glasgow. “And marginalia provide layers of information as to the various human hands that have shaped their form and content.” From intriguingly detailed illustrations to random doodles, the drawings and other marks made along the edges of pages in medieval manuscripts—called marginalia—are not just peripheral matters. “Both tell us huge amounts about a book’s history and the people who have contributed to it, from creation to the present day.”

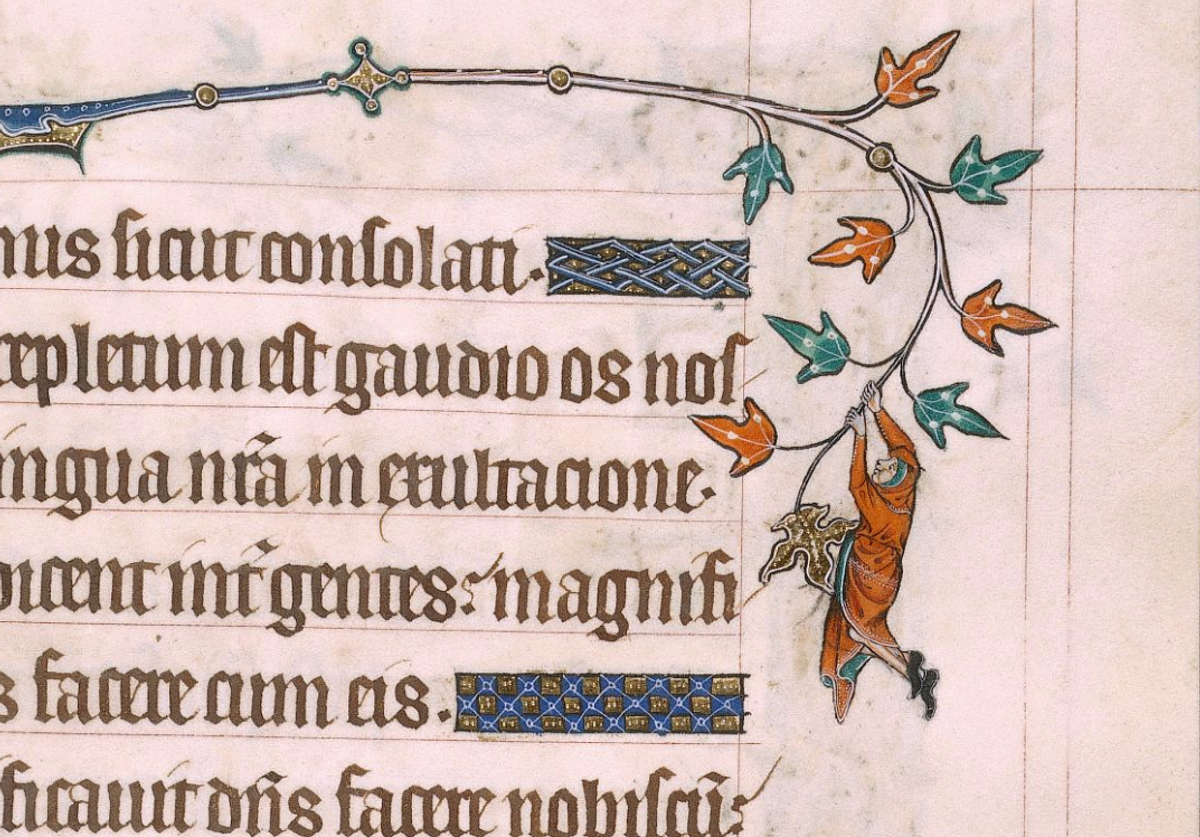

On medieval pages, marginalia can run from the decorative to the bizarre, which Green engagingly documents on her Instagram account. There are two broad categories of marginalia: illustrations intended to accompany the text and later annotations by owners and readers. Both can be vehicles for delight, disgust, and befuddlement.

An example of useful intentional illustrations can be found, for those with a strong stomach and an interest in medieval medicine, in John of Arderne’s Mirror of Phlebotomy & Practice of Surgery, which is located at the Glasgow University Library. Known as the “Father of English Surgery,” Arderne produced several important medical texts in the 14th century. Fortunately, he was also a prodigious illustrator. His textbooks contain ample amounts of delightfully detailed (and occasionally rather gruesome) illustrations.

“The margins are full of images of disembodied body parts, plants, animals, even portraits of cross-eyed kings, which relate to the main body of text and act as a mnemonic for the reader,” Greene says. “Even though you open the manuscript knowing it is a medical text designed for practical use, nothing quite prepares you for seeing a disembodied leg, posterior, or penis pointing at salient parts of the text!”

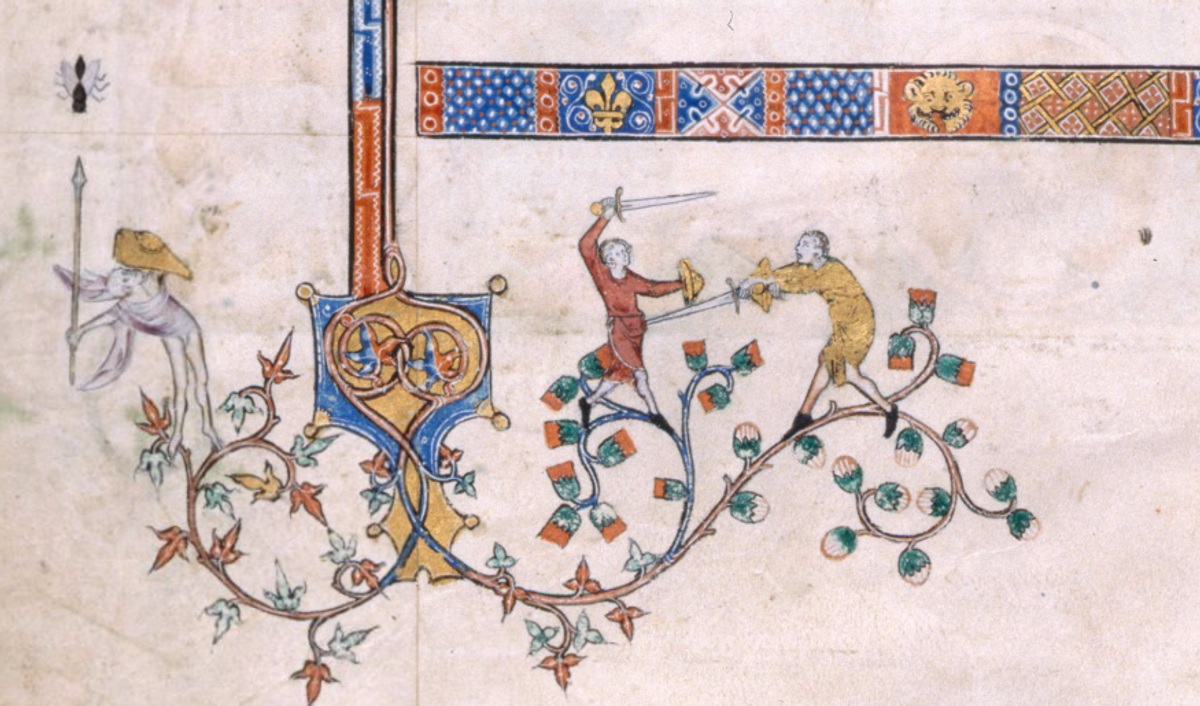

In Arderne’s texts the marginalia has a clear purpose, but in other manuscripts the meaning of the drawings can be indecipherable. There are countless examples of unusual marginalia—monkeys playing the bagpipes, centaurs, knights in combat with snails, naked bishops, and strange human-animal hybrids that seem to defy categorization.

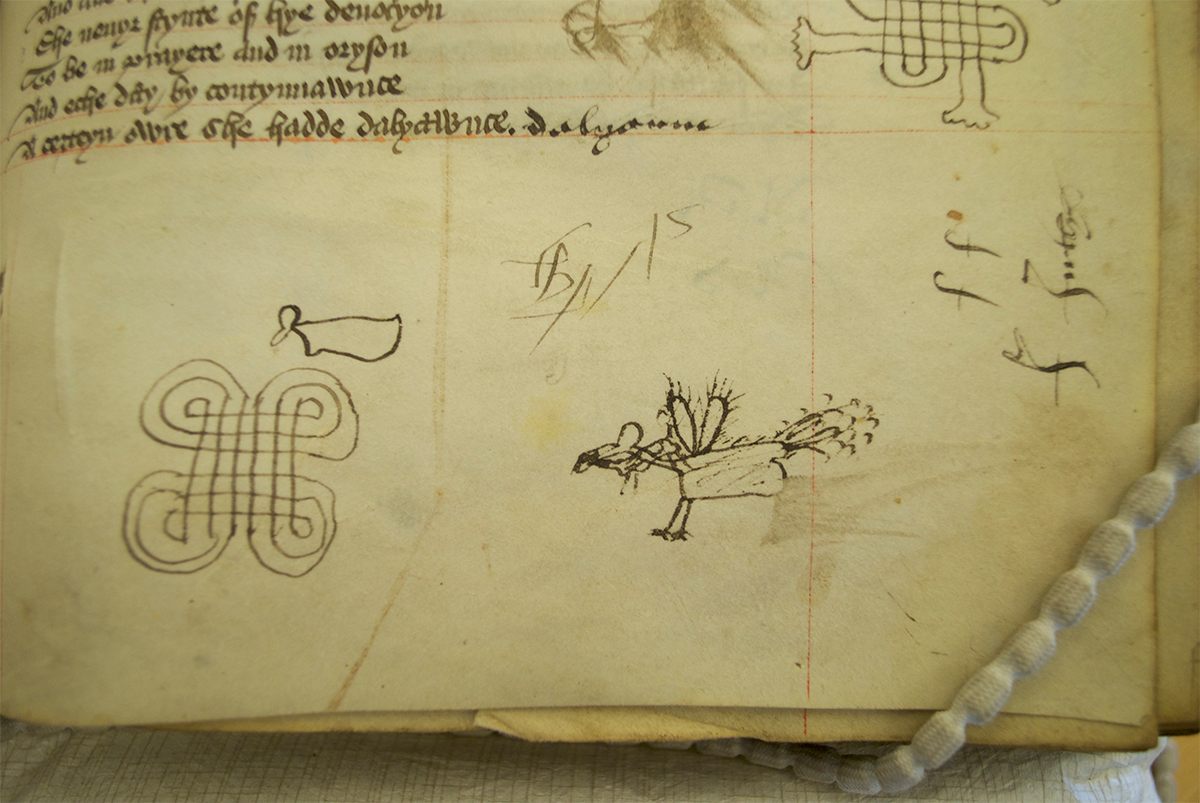

Beyond these weird and wonderful illustrations, random doodles from later readers are also significant. “Each time we find an annotation in the margin, the form it takes gives us an insight into the kinds of encounters or interactions those people had with these books,” says Green. For medieval texts, “a gloss, biblical reference, or some commentary suggests the user was reading the text closely, compared with pen trials which show scribes breaking in a new nib, while other marks and illustrations often give the impression of a bored reader using the blank parchment of the book as we might use scrap paper. It is essentially a form of archaeology, but for books.”

If the idea of doodling in a book either appeals to you or repulses you, then consider the pages of a copy of the long 15th-century poem Life of Our Lady, by John Lydgate. It is adorned with pages of doodles from the 16th century: “illustrations of dogs, defecating goats, peacocks with stick-figure riders, boats with tiny passengers aboard, and other marginal marks that look like very young children’s scribbles.”

Atlas Obscura has compiled a selection of doodles and drawings from medieval manuscripts. They are, by turns, silly, dramatic, and puzzling—but always illuminating about the way scribes and readers connected with the texts.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook