Has Any Human Lived As Well As Fidel Castro’s Favorite Cow?

Fidel Castro with Ubre Blanca (White Udder). (Photo: AFP Photo/Prensa/Getty)

Outside the gates of a small dairy farm in the Cuban city of Nueva Gerona stands a life-sized statue, cast in gleaming white marble, of the country’s most sacred cow. The statue is not of Che or Fidel, but another hero of the revolution—a worker so tireless, so selfless and so extraordinarily productive that she became a symbol of national pride to millions of Cubans, who eagerly followed reports of her latest record-breaking feats. When she died, she was given military honors, a full-page obituary in the state newspaper and a heartfelt eulogy from the poet laureate, while the country’s most popular musicians wrote songs celebrating her remarkable life.

Her name was Ubre Blanca, or White Udder, and she might be the most famous cow who ever lived.

How did a humble bovine become Cuba’s most beloved revolutionary mascot? Unsurprisingly, it had a lot to do with Fidel Castro, whose taste for fresh milk was so well-documented that the CIA once tried to assassinate him by slipping Botulinum toxin into his daily milkshake. After seizing power in 1959, Castro was determined to make the white stuff a staple of the national diet, and had big plans for the Cuban dairy industry, which he boasted would manufacture better cheese than the French, better chocolate than the Swiss, more flavors of ice cream than the Americans and “so much milk that we could fill Havana bay with it.”

Cows roaming in Cuba. (Photo: Martin Cathrae/flickr)

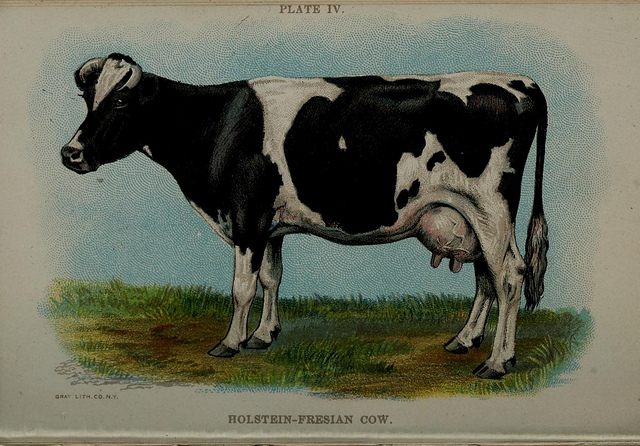

There was only one problem: Cuba’s native cattle, the Cebu, were raised for meat, not milk, and the tens of thousands of milk-producing Holstein cows that had been imported at huge expense were ill-suited to the island’s tropical climate. Castro’s solution was to use artificial insemination to create a new genus of “supercow”, combining the hardiness of the Cebu with the high yields of the Holstein. “It means that a Cebu cow which produces 1.5 litres [0.3 gallons] of milk can bear a calf that can produce 8 or 10 litres [2 gallons],” he explained in the 1966 speech announcing his new breeding program. “It means that these cows will bear calves in 1967. In 1969, they will be serviced. If in 1970 we have approximately 400,000 cows, in 1971, they will multiply to nearly one million more.”

Ubre Blanca, born in 1972, was a product of those genetic experiments, and the program’s only real success—but what an exception to the rule she was. Obsessed with creating a “100-litre cow”, Castro kept a close eye on Ubre Blanca’s progress, and in June 1982 she became a national hero when she produced 109.5 litres (28.9 gallons) of milk in a single day, smashing the previous record set by an American cow, Arleen, in 1975—a priceless propaganda victory over the Yankee imperialists. The following month, she broke another record when it was discovered that she had yielded 24,269 litres (6,411 gallons) over a 305-day lactation cycle. Castro called her “our great champion,” and not without justification, as—Ubre Blanca’s daily output was almost four times that of an average cow.

Fidel Castro visits Washington DC in April 1959. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Of course, no “average” cow ever lived like Ubre Blanca did: at her state-of-the-art, air-conditioned stable in Neuva Gerona, she received round-the-clock care and attention from a specially-selected team of handlers, and was watched over by armed military escorts. Soothing music was piped into the stalls during each of her four daily milkings, and her food was tested on other animals before she ate it, lest anyone attempt to poison her. Yet for all his legendary paranoia, Castro couldn’t resist showing her off to journalists and visiting dignitaries, who were invited to marvel at that bulging, bounteous udder, which was known to reach over six and a half feet in circumference after calving.

Unfortunately, like the rest of Fidel’s supercows, none of Ubre Blanca’s offspring could match their mother’s productivity, and as time went by, the stress and expectation placed on her took a severe physical toll. In 1985, after her third pregnancy resulted in a worrying proliferation of glandular tissue, she was transferred to the National Center for Agricultural Health in Mayabeque to have her eggs frozen for future research. This procedure would unexpectedly aggravate a tumor that had been forming on her rump and shortly thereafter Ubre Blanca was euthanized, her body embalmed and put on permanent display at the National Cattle Health Centre near Havana.

Ubre Blanca was part-Holstein, part-Cebu, and capable of producing record quantities of milk. (Photo: Biodiversity Heritage Library/flickr)

Castro was so distraught that he ordered a massive portrait to be hung from the exterior of the National Library, so he could look upon her from his office window.

With Ubre Blanca gone and the supercow program abandoned, Castro sought alternative methods of boosting milk production, which suffered greatly during the economic and agricultural crisis brought on by the collapse of the USSR. “If we discover a technique, if another Ubre Blanca is found, or a prodigious descendant of Ubre Blanca, what can prevent us from immediately applying this practice everywhere, to all the cows of Cuba?” he asked a gathering of scientists in 1987, possibly referring to a quixotic scheme he was working on to put genetically-engineered dwarf cows into every home. In the meantime, milk became so scarce that rations were made available only to pregnant women and children under seven; even today, a kilo of powdered milk costs $7.50, with the average monthly wage between $20 and $30.

Staple items for sale in a bodega in Cuba in 2010, including powdered milk. (Photo: ©Jorge Royan/oyan.com.ar/CC-BY-SA-3.0/WikiCommons)

There was one final twist to come, however. In 2002, word got out that Castro, inspired by Jurassic Park and Dolly the Sheep, had tasked the Havana Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology to end the country’s chronic milk shortage by cloning an entire herd of Ubre Blancas from genetic samples harvested before her death. The project’s lead scientist was initially optimistic of their chances, telling reporters that they were “very close” to being able to clone a live cow, though they did not yet have the capacity to do it from 17 year-old frozen tissue. So far as anyone knows, it’s a challenge they’ve never managed to overcome: in death, as in life, Ubre Blanca remains a truly singular cow.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook