The Cast Iron Coffin That Was Too Creepy Even for the Victorians

The “Fisk Mummy” in the Pink Palace Museum in Memphis (all photographs by the author unless indicated)

The “Fisk Mummy” in the Pink Palace Museum in Memphis (all photographs by the author unless indicated)

In 1848, Almond Fisk patented a metal coffin he believed would revolutionize death. One problem: some people thought the burial case with its human contours was creepy as hell.

The ”Fisk Airtight Coffin of Cast or Raised Metal” — also known as the “Fisk Mummy” — was designed to preserve the corpse in a cast-iron mummy-shaped case for travel or other delayed interment, and also to keep from spreading disease as outbreaks of yellow fever and cholera were being blamed on overcrowded cemeteries. This was especially true in the United States where Fisk was born, where formerly contained cities like New York had spilled beyond their bounds many times, including in their cemeteries where churchyards were packed to the topsoil, raising the cemetery ground several feet above the surrounding sidewalk. But with a metal sarcophagus, this grotesque collapsing of the flesh into decay could be contained, even slowed.

via United States Patent Office

As Fisk wrote in his 1848 patent: “From a coffin of this description the air may be exhausted so completely as entirely to prevent the decay of the contained body on principles well understood; or, if preferred, the coffin may be filled with any gas or fluid having the property of preventing putrefaction. “

The molded coffin, in fitting with elaborate Victorian mourning, was heavily decorated with symbolism like angels, thistles, roses, and on one found in an unmarked grave in Missouri in 2006, oak leaves, acorns, and berries. The coffin itself was shaped like a shrouded corpse, the edges of the draping delicately molded. And at the head was perhaps the most unsettling feature: a little window to view the face of the dead.

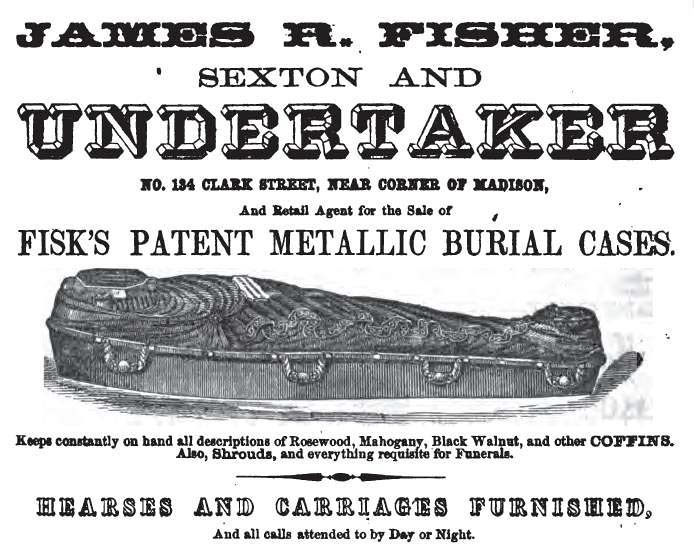

Ad for the Fisk burial cases (via northwestern.edu)

As Harold Schechter cites in his book The Whole Death Catalog: A Lively Guide to the Bitter End, in one ad for the Fisk coffin, it boasted that this window allowed mourners “to behold again the features of the departed.” Unfortunately for Fisk, people found it all a little unsettling, especially the uncanny, otherworldliness of the metal case like some Industrial Age warping of Ancient Egypt. As Schechter writes, a later ad for a different version stated that it aimed to cut back on “the disagreeable sensation produced by the coffin on many minds,” or basically to make it less creepy.

Fisk case in the Pink Palace Museum in Memphis

Fisk case in the Pink Palace Museum in Memphis

The coffins were crazy expensive for the time — going for between $7 and $40 when a standard wood box would only cost a couple of bucks. But their price tag and upsetting countenance weren’t the greatest misfortunes for Fisk’s dreams of modern entombment. In 1849, only a year after his patent, his factory on Long Island in New York burned to the ground and he suffered injuries which would kill him the following year. (It’s hard to find a concrete report, but one has to assume he was placed in a metal casket of the utmost splendor.) Yet while his New York City showroom went with him, the coffins continued on with different manufacturers, although not without their continued misfortune with public relations.

Fisk case in the Pink Palace Museum in Memphis

Fisk case in the Pink Palace Museum in Memphis

Detail of the metal “shroud”

The airtight nature of the coffin could have had an unintended side effect: explosion. As the body breaks down and releases its “leakage,” it needs some, for lack of a better expression, breathing room. In 1858, the Chicago Press ran a sensational story entitled “Explosion of a Metallic Coffin” that claimed one of Fisk’s blew open, corpse and all.

However, in a letter to the New York Times a representative of Raymond & Co. — which was then manufacturing the Fisk coffins — rebuffed these accusations, stating they hadn’t even sold to people in Chicago: “We could give many instances from among the many thousands of cases made and sold by us for the last six years, that have been submitted to the severest tests in the transportation of bodies, not only to and from distant parts of our country, but to Europe and the West Indies. Perhaps no more notable occasion or severe test was ever applied than in the case of the transportation of the remains of the Hon. Henry Clay from Washington, during the hottest weather in July, with many delays to their final resting places in Kentucky, which was done to the entire satisfaction of the Senate Committee who had the matter in charge.”

The face plate, hinged over the window

The production of the Fisk mummies ended in 1853 or 1860 (reports vary). Being that most that were made remain underground, they’re incredibly rare to see, but those that are unearthed tend to become museum pieces while the bones (sometimes well-preserved, just as Almond Fisk promised) are reinterred without their fancy coffins. One that held a man who died in 1854 was accidentally found when a plow burst into a burial vault constructed with 2,000 handmade bricks in Tennessee. It’s now on display in the Pink Palace Museum in Memphis — appropriately, a city a bit obsessed with its Egyptian namesake with their own giant pyramid downtown — in a rather eerie dark room by itself where it rests on a pile of bricks (it’s unclear if these are the same masonry from the burial vault).

You can also find Fisk mummies on display at the Museum of Appalachia in Clinton, Tennessee; the Herr Funeral Home Memorial Museum in Collinsville, Illinois; the Canton Historical Museum in Collinsville, Connecticut; and one in a grand windowed funeral carriage at the Rural Life Museum in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. And of course, they still rest quietly in crypts and catacombs — 19th century Victorians encased in their own visions of a better afterlife.

Morbid Mondays highlight macabre stories from around the world and through time, indulging in our morbid curiosity for stories from history’s darkest corners. Read more Morbid Mondays>

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook