NASA Stole the Rocket Countdown From a 1929 Fritz Lang Film

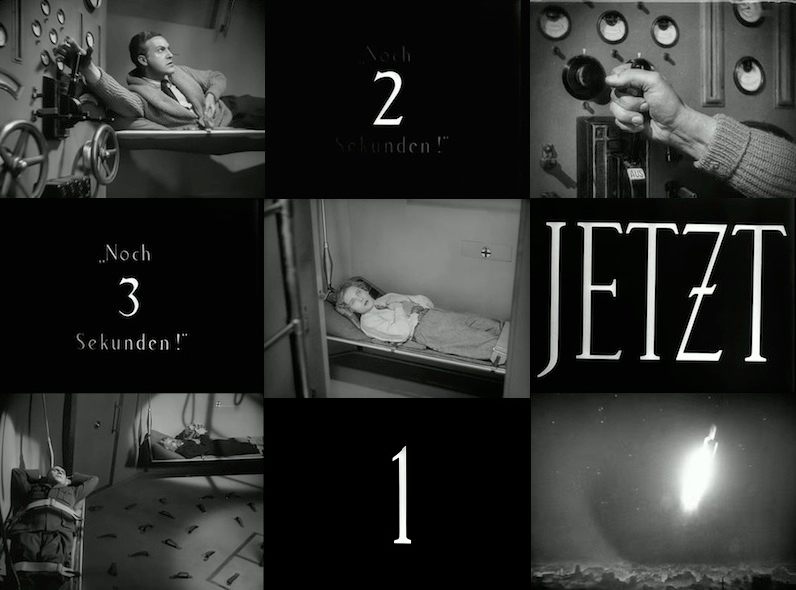

A series of images from the countdown sequence of Fritz Lang’s Woman in the Moon. (Image: Frau im Mond/Youtube)

On December 1, 2014, NASA retired a historic piece of equipment at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. It wasn’t a rocket, or even a deep space nine-iron—it was the original countdown clock, an analog display the size of a titan’s wristwatch that stood across the river from the rocket launch site and stoically ticked off the seconds until blastoff.

Countdown clocks allow technicians and astronauts to synchronize their moves throughout a rocket launch sequence, from T-minus 43 hours all the way until the final ignition. But their appeal goes way beyond practicality. The clock also serves as the visual version of a whistling teakettle, allowing spectators to ramp up their excitement as launch time draws nearer. When those last few seconds tick away before a launch, it’s dramatic, emotional—even cinematic. Which makes sense considering the rocket-launch countdown clock wasn’t invented by meticulous engineers, but dreamed up by a filmmaker: science fiction pioneer Fritz Lang.

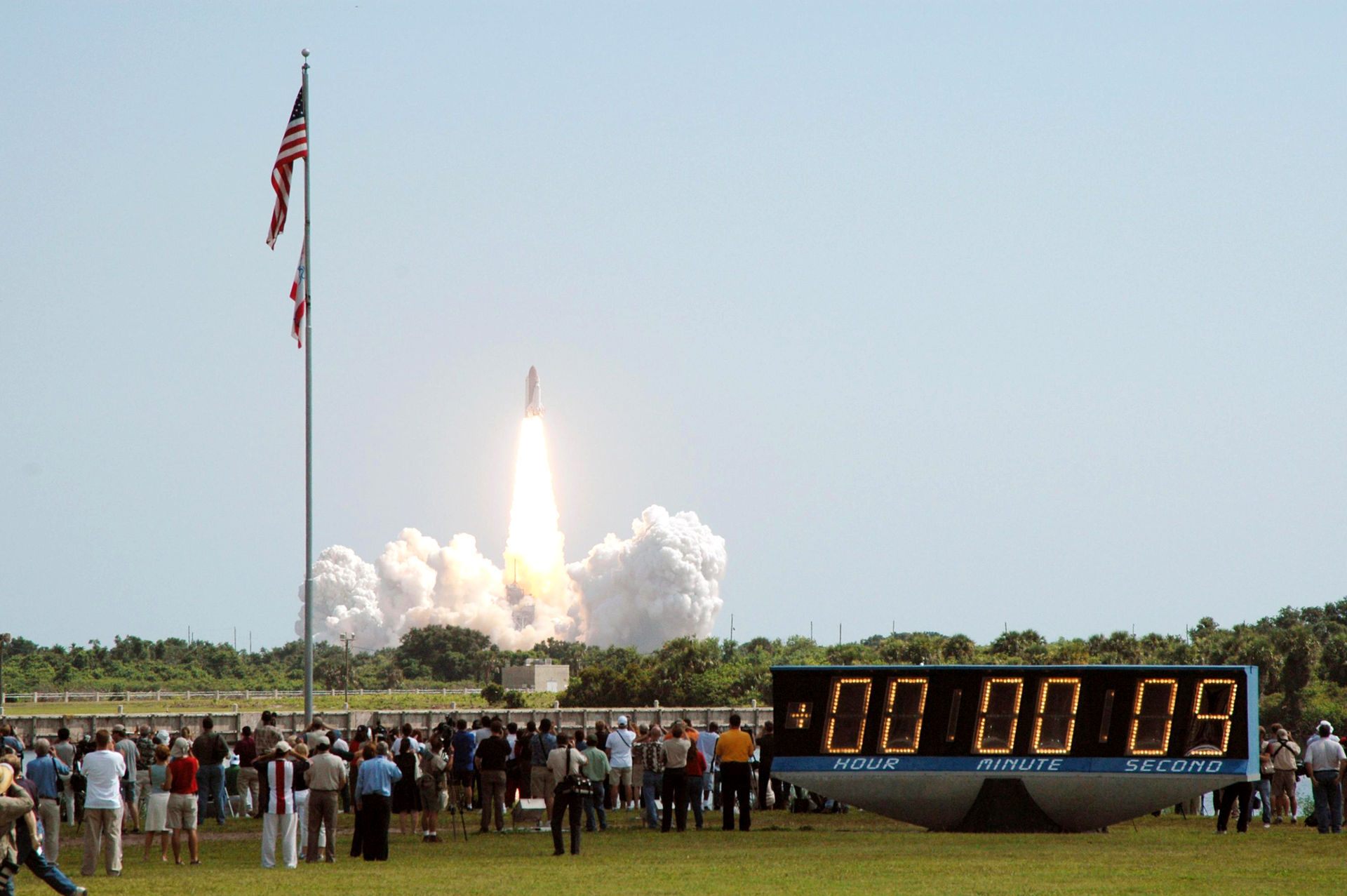

The countdown clock, switching into elapsed time mode after the 2005 launch of Space Shuttle Discovery. (Photo: NASA/KSC Public Domain)

As media scholars Tom Gunning and Katharina Loew detail in “Lunar Landings and Rocket Fever: Rediscovering Woman in the Moon,” one little-known Lang movie “not only predicted the future of rocketry,” but “actually played an effective role in its early development.” In 1927, Gunning and Loew write, Lang was desperate for a hit. Metropolis, though today considered an undisputed classic, was a box office flop in its own time, and Lang’s production company, Ufa, was threatening to cut him off. To make matters worse, Lang was a silent filmmaker, and sound was rapidly becoming the hot new cinematic trend. Lang’s next movie had to be so exciting that the public wouldn’t even notice how quiet it was.

Luckily, he had the perfect subject matter right at his fingertips. In the mid-1920s, Germany had a bad case of rocket fever. Still getting over the trauma of World War I, and unsure how to reconcile the power of new technology with the power of old-school spirituality, the public turned to space travel as a literal escapist fantasy, writes media scholar Katharina Loew.

The surprise bestseller of the decade was a popularized version of Die Rakete zu den Palnetenräumen (By Rocket into Planetary Space), a Transylvanian high school teacher’s rejected dissertation that argued scientifically for the possibility of space travel. Soon, enthusiasts at Germany’s new Society for Space Travel were putting out a monthly magazine, Die Rakete (The Rocket), tinkerers were building rocket-powered sleds and cars, and readers were snapping up the latest spaceflight novels.

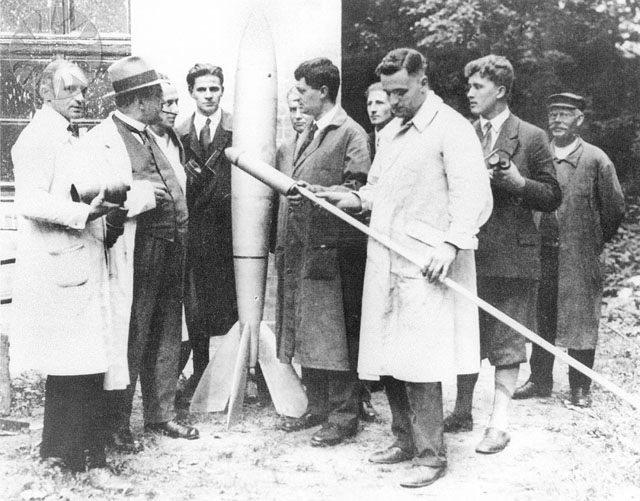

Members of the Society for Space Travel in 1930. Oberth is directly to the left of the rocket. (Photo: Public.Resource.org/Flickr)

One of these novels, Die Frau im Mond, happened to be written by Thea von Harbou, Lang’s longtime collaborator and then-wife (the two later separated, after von Harbou decided to throw her lot in with the Nazis). The book, which follows a group of backstabbing moon prospectors, is a rollercoaster ride of love triangles, business intrigue, and lunar gunfights, and Lang set out to turn it into a film. While writing the novel, von Harbou had researched spaceflight meticulously, and Lang, wanting his film to be equally grounded in scientific possibility, hired Hermann Oberth—the Transylvanian teacher who had started the whole space craze—as the film’s scientific advisor. Oberth hightailed it to Berlin.

What followed was a historic collaboration between art and science. For each obstacle that faced the spacefaring characters—rocket design, oxygen shortages, zero gravity—Oberth would calculate the most probable solution, and Lang and his crew would make it happen. Other German rocket enthusiasts, including Willy Ley and Max Valier, gravitated to the set to throw in their two cents, and to watch as their wildest dreams materialized. Lang felt unfettered by his supposed budget constraints—in one memorable line item, he ordered 40 carloads of sea sand to be trucked in and roasted to form the perfect moonscape. The only limits were the scientists’ calculations and Lang’s imagination.

Lang on the set of Woman In The Moon, with cameraman Curt Courant. (Image: WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Lang and his advisors came up with a number of spacefaring features that, years later, showed up on actual launchpads. The astronauts lock into footstraps to keep from floating around, and the rocket itself has multiple stages and engines that it jettisons one at a time, presaging modern designs. Another prescient decision came together in editing. The launch itself is a tense moment, worthy of a dramatic buildup. Lang remained vehemently anti-sound, and refused to add any effects, so loudly revving up the blasters was out of the picture. Instead, he decided to use a less obvious suspense technique: intertitles.

As the astronauts lie in their bunks, eyes wide and jaws tense, the screen cuts to an announcement: “Noch 10 Sekunden-!”—10 seconds remaining! The mission leader grips the firing lever—”Noch 6 Sekunden!” The numbers get bigger, filling the screen: 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, JETZT! Now! The lever lowers, and the rocket blasts out of the water. Nearly a hundred years later, it still gets the heart pumping.

Although some earlier novels and films used count-ups, this was the first time the rocket met the countdown. Since then, they’ve been inseparable. The film’s space advisors brought lessons they learned from the film set back with them to the Society for Space Travel, where they found that loudly timing launches to the second was not only dramatic, but helpful. When NASA launched its first successful satellite, Explorer 1, in 1958, newsreels broadcasting the event breathlessly announced, “the moment is at hand, the countdown reaches zero!”

As for Frau im Mond, audiences ate up the gadgets and moonscapes, and it was the year’s highest-grossing film. Critics weren’t so keen, though, and this particular Lang film has largely been lost to time, overshadowed by more well-rounded classics like M and Metropolis. But every time a real rocket leaves its launchpad, spurred on by people worldwide mouthing “ten… nine… eight,” the spirit of Frau im Mond takes off with it.

This story appeared as part of Atlas Obscura’s Time Week, a week devoted to the perplexing particulars of keeping time throughout history. See more Time Week stories here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook