National Doughnut Day Began With an Ingenious Woman on a WWI Battlefield

Lt. Colonel Helen Purviance fried dough on the frontlines.

Each year, on the first Friday of June, Americans celebrate National Doughnut Day with free doughnuts at Krispy Kreme and Dunkin’ Donuts and, sometimes, with doughnut bouquet deliveries. But as a Salvation Army video demonstrates, the history of the holiday is also the story of World War I—and of the woman who made doughnuts an American staple.

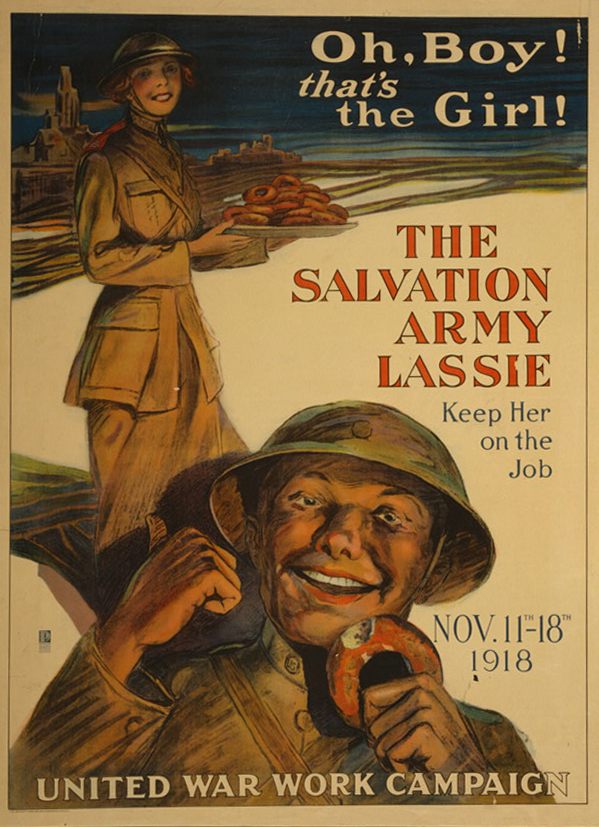

In 1938, capitalizing on the growing doughnut craze, the Salvation Army created National Doughnut Day to raise funds and to promote its efforts “provid[ing] spiritual and emotional support for U.S. soldiers” during the First World War.

After the United States entered World War I in 1917, a group of 250 predominantly female volunteers journeyed to the front lines of France and moved into tents, offering soldiers food and clothing. There, many soldiers began requesting something sweet to eat, but because the volunteers lacked access to ovens, one woman—Lt. Colonel Helen Purviance, an Indiana native who enrolled in the Salvation Army in 1906—came up with a solution: doughnuts.

Using little besides flour, sugar, baking powder, cinnamon, and canned milk, Purviance and another volunteer, Margaret Sheldon, began making dough and frying it in oil. “I was literally on my knees when those first donuts were fried, seven at a time, in a small pan,” Purviance said later. “There was a prayer in my heart that somehow this home touch would do more for those who ate the donuts than satisfy a physical hunger.”

Because there was so little proper cooking equipment, the women needed to improvise: they used wine bottles as rolling pins, a “lamp chimney to cut the doughnut,” and “the top of a coffee percolator to make the hole.” When the pans ran out, they fried doughnuts in soldiers’ helmets.

The sweet treats were an instant hit with the soldiers, who consistently crowded around the Salvation Army tents looking for more. Whenever they saw Salvation Army volunteers, they celebrated the arrival of the “doughnut girls.”

Astoundingly, an April 1938 New York Times article reported that Purviance “cooked no fewer than 1,000,000 doughnuts for the United States fighting forces,” describing her “cooking doughnuts under shellfire with a cutter made out of an evaporated milk can and a shaving-stick holder and a grape-juice bottle for a rolling pin.”

American World War I soldiers were hooked, and when they returned home, they hungered for more doughnuts, which had previously been a niche food. Purviance turned them into an American classic. According to the book Donuts: An American Passion: “the Salvation Army was among the strongest charitable forces in America—and their chosen totem, the donut, was an ingrained symbol of home.”

Soon after, an entrepreneur named Adolph Levitt capitalized on the burgeoning interest in doughnuts, debuting the first doughnut machine in 1920. A little over a decade later, he was making $25 million a year in sales.

Despite her success, after the war Purviance stopped making doughnuts because they reminded her of the suffering she witnessed. When the New York Times reported on her in 1938, she had only fried doughnuts twice since returning home.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook