New York’s First Female Crime Boss Started Her Own Crime School

Marm Mandelbaum, the Queen of Fences, turned street rats into professional criminals.

Organized crime in New York is often portrayed as a boy’s game, but one of the first and most influential crime bosses in the history of the city was a Prussian immigrant known as “Mother” or “Marm” Mandelbaum.

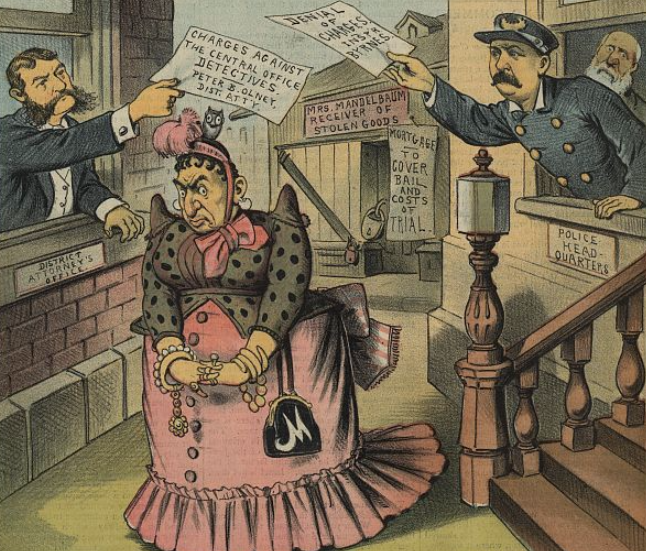

Also called “The Queen of Fences,” this imperious and powerful woman became one of the most well-connected criminal figures of her day, buying stolen goods and reselling them, financing criminal endeavors, and even creating a school for young criminals.

Fredericka Mandelbaum came to America with her husband Wolfe in 1848, landing in New York and opening a general store. In the beginning, Mandelbaum and her husband worked as flamboyant street peddlers, building relationships with both the hordes of aimless children and the petty thieves looking to get rid of their stolen loot. By 1865, Mandelbaum had opened a shop on Clinton Street to act as the front for her burgeoning criminal operation. Her husband, described by Sophie Lyons—a woman who would later become Mandelbaum’s star student and protégé—as “rather weak-willed for his calling, lazy, and afflicted with chronic dyspepsia,” took a backseat while Marm built a criminal empire.

Fencing stolen items became Mandelbaum’s main hustle. A criminal would steal anything from jewelry to furniture, and sell it to Mandelbaum, who would turn around and sell it to another buyer. Mandelbaum’s favorite items were bolts of silk and diamonds, both of which she could buy on the cheap and sell at a huge mark-up. But she would take anything. “Following the Great Chicago Fire, someone showed up at her haberdashery shop with a herd of goats they’d stolen during the fire, and she took them,” says J. North Conway, author of Queen of Thieves: The True Story of “Marm” Mandelbaum and Her Gangs of New York. As Mandlebaum’s power grew, she branched out into financing bank robberies, and supporting all manner of criminal enterprise ranging from blackmail to theft to burglary.

Mandelbaum was six feet tall and said to be between 200 and 300 pounds, giving her an imposing physical presence. But it was her formidable network that allowed her criminal power to grow. She was known to fastidiously bribe and pay off police, local politicians, and judges, who allowed her operation to become a criminal ring worth millions. “At some point, she came to understand the American system,” says Conway. “The American is system is, ‘You get what you pay for.’”

Mandelbaum never got her hands dirty, instead building an inner circle of burglars, pickpockets, and robbers. To grow and support this network, Mandelbaum is said to have created a school that would train the many children living on the streets to be criminals. “The city was inundated at the time, with orphaned children. ‘Street rats,’ they called them,” says Conway. While no official transcripts of the curriculum seems to exist, Mandelbaum’s Grand Street School became maybe the first and most successful training center for crooks in the city, according to Conway.

The school was opened around 1870 behind a storefront on Clinton and Grand Street. Mandelbaum invited both young men and women to come and learn the criminal trades from professional thieves, pickpockets, and conmen. When young ne’er-do-wells enrolled in the school they started off learning about smaller crimes like pickpocketing and petty theft. They would be taught about things like misdirection and the finer points of thieving, then, if they had a knack for it, their training would advance. “If you were doing very well, you graduated up into other, more important things, which would include outright robberies and scams,” says Conway. Other higher level subjects included safe-cracking, blackmail, and burglary.

The star pupils would eventually move on to work directly for Mandelbaum. Her enterprise had a symbiotic relationship with the criminal community in that she needed a constant flow of thieves bringing her merchandise, and they needed a quick and reliable place to sell their ill-gotten gain.

One of Mandelbaum’s greatest students was Lyons, a master blackmailer and thief who, after working for Mandelbaum, went on to have her own impressive criminal career, becoming known as the “Princess of Crime.” Conway says that one of her scams involved luring men to a hotel room, letting them get naked, then stealing their clothes and extorting them for their cash to get them back.

In the early 20th century, however, Lyons reformed, denouncing her criminal career and her association with Mandelbaum’s training. “[In her autobiography] she basically decried the tutoring that Mandelbaum had given her, saying that she was taking advantage of her youth and innocence, leading her down a path of crime and so forth,” says Conway.

Whether or not Mandelbaum’s school was luring impressionable youth into a life of crime, her willingness to train and employ women in her crime ring created opportunities that were simply not available elsewhere. “Despite the fact that it was in the arena of crime, Mandelbaum was credited with being one of the first feminists, because she was able to get women jobs in which they made more money and were able to use their skills in better ways than they did working in factories or as maids,” says Conway.

The Grand Street School operated for only about six years, closing down around 1876. Mandelbaum shut down the school when she found out that the son of a police official had enrolled. Rather than let this suspicious new student learn the ropes, risking her entire empire, she shuttered the school.

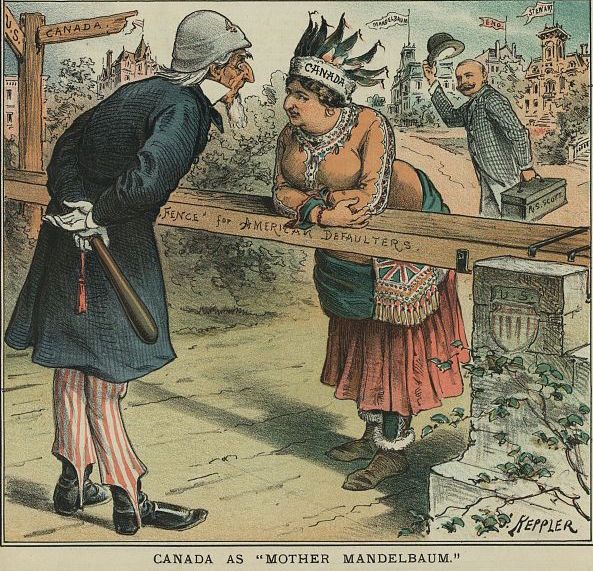

Even after the closing of the school, Mandelbaum’s criminal empire continued to grow and thrive. In addition to the apartments above her Clinton Street shop where she conducted most of her business, Mandelbaum eventually had to keep a pair of warehouses in the city to hold all of her dirty merchandise. Finally in 1884, members of the Pinkerton detective agency managed to bring her criminal reign to an end. “The silk was her undoing,” says Conway. “The Pinkertons had tagged a bolt that they knew was stolen. She bought it, and at that point they closed in on her.” Rather than face trial, Mandelbaum managed to escape to Canada, reestablishing herself with over a million dollars worth of cash and diamonds.

Mandelbaum died in 1894, while still living in criminal exile. Her body was returned to New York to be buried, and a number of the mourners at her funeral reported being pickpocketed. Mandelbaum and her school may not have been on the right side of the law, but in her role empowering the women she trained and employed, she was on the right side of history.

![Anne Bonny and Mary Read were both "convicted of piracy at a Court of Vice Admiralty [and] held at St. Jago de la Vega on the Island of Jamaica, 28th November 1720," according to the inscription accompanying this 1724 Benjamin Cole engraving from <em>A General History of the Pyrates</em>, by Daniel Defoe and Charles Johnson.](https://img.atlasobscura.com/5_kDHgENxQkc0QzZuPs_kICvmEP5JNCV8bcXDI7m5Do/rs:fill:600:400:1/g:ce/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy81NDQ0ZGNiMi1m/YzRkLTQ4YjUtYTVh/MC0xYzU2ZDliOTY0/YjY1NGNkMWI4MWEw/OTExMDM5ZTZfQW5u/ZSBCb25ueSBhbmQg/TWFyeSBSZWFkIC0g/RmVtYWxlIFBpcmF0/ZXMgaW4gMTgwMHMu/anBn.jpg)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook