Object of Intrigue: Banknotes for a Japanese-Occupied Hawaii

(Image: National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History)

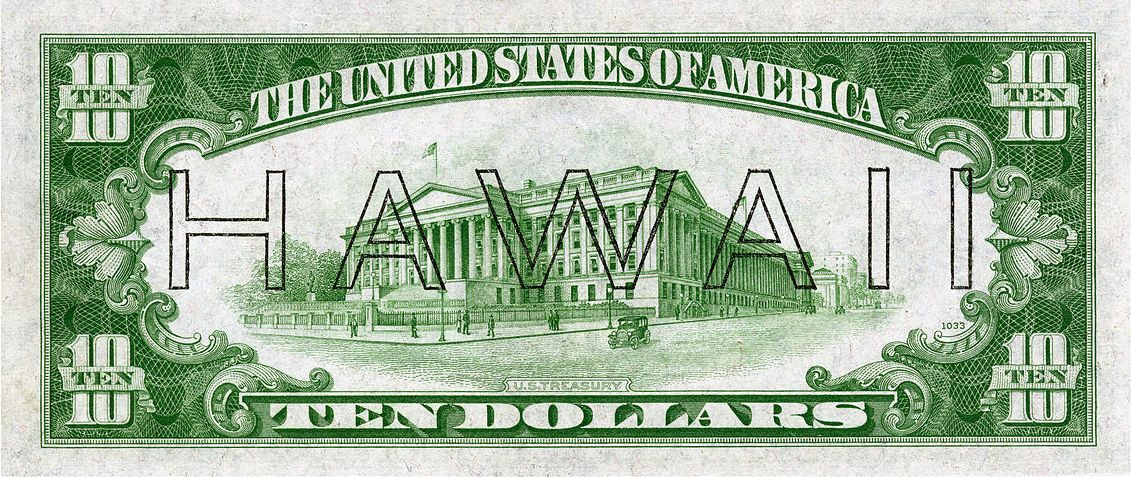

In early 1942, the United States government began issuing a special set of banknotes custom-made for Hawaii. The back of each note looked identical to the existing U.S. paper currency apart from one major difference: the word “HAWAII” was stamped across it.

The design of these notes wasn’t the most elegant—the “HAWAII” looked as though it was inscribed by someone with a black ballpoint pen and a ruler. But that’s understandable, given their circumstances: these banknotes were an emergency series, rushed to print in the months following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. The idea was that if Japan invaded Hawaii, the U.S. government could immediately identify and devalue the state’s currency so it would be worthless to the Japanese.

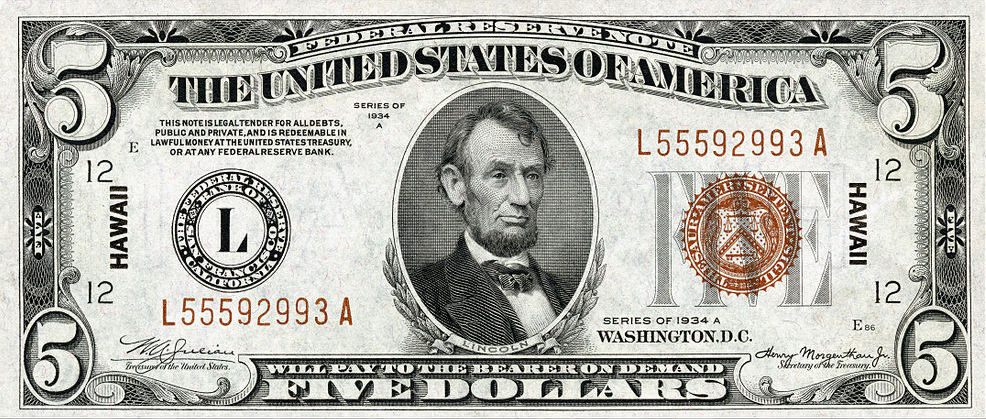

“The Federal Reserve notes were issued in the San Francisco Federal Reserve District, which included Hawaii in its jurisdiction,” says Mark Anderson, Numismatic Consultant to the Museum of American Finance. If the need had arisen, ”the notes’ distinctive features would have allowed prompt and easy identification.” In addition to the big HAWAII stamp, each note featured brown treasury seals instead of the usual blue or green, and had “Hawaii” printed vertically in small black block letters on the front.

Honest Abe, Hawaiian style. (Image: National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History)

Of course, the standard American currency already circulating on the Hawaiian islands presented a problem. The U.S. government made an attempt to snap it up quickly, lest it fall into the hands of the Japanese. In January 1942, the government recalled all paper money in Hawaii, except for a per-person allowance of $200. (Businesses were permitted to hold onto $500.) As the Honolulu Advertiser tells it, the actions were drastic:

Everybody was supposed to turn in their cash and securities. Patriotically, they did so—$200 million worth. Then the government had to burn all this money. It was taken to Nuuanu Mortuary, but the crematory there couldn’t handle such a mass of paper currency and securities. So the rest of it went up in smoke at the ‘Aiea Sugar Plantation mill.

The new notes prevailed, and served as Hawaii’s currency through the rest of World War II and for several years after. Because Japan never invaded Hawaii, the notes were never demonetized. In fact, they are ”still legal tender today,” says Anderson, though they “have not been seen in circulation for many decades now.” Coin dealers sell them, but they’re not too rare or valuable—you can get a full set for under $200. (If you’d like to see the notes without having to buy them, visit the Museum of American Finance in New York, where you’ll find a set on display in the America In Circulation exhibit.)

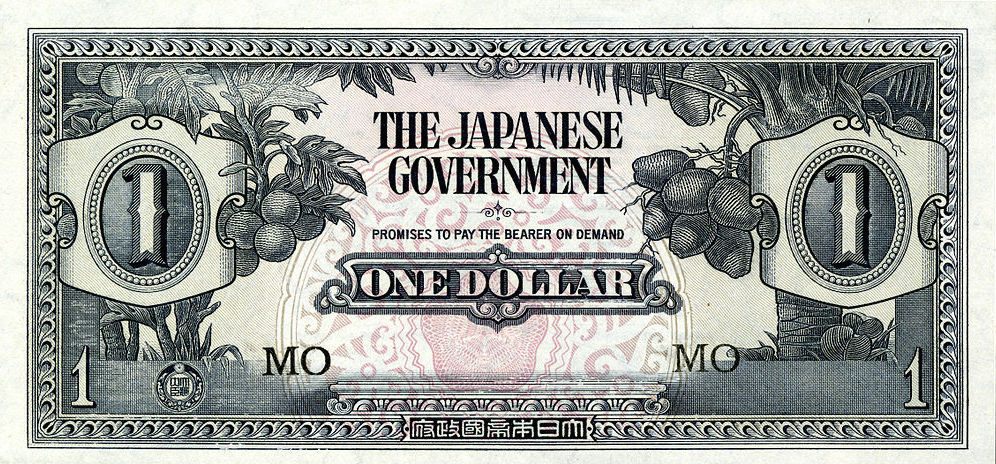

Japan never invaded Hawaii, but it did occupy the Aleutian Islands of Alaska, and a number of Southeast Asian and Pacific territories during World War II. These included the Philippines, Burma, Malaya (a territory now part of Malaysia and Singapore), Hong Kong, Singapore, Thailand, and what was then French Indochina—today’s Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. The Japanese occupation of these places had its own currency-related consequences.

In 1942, the Japanese Military Authority began issuing what it called “Southern Development Bank Notes,” known more realistically as “Japanese invasion money.” This paper currency, emblazoned with “The Japanese Government,” was intended to replace the local currency of each occupied territory. Here, for example, is a Japanese note issued in Malaya between 1942 and 1945:

(Image: National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History)

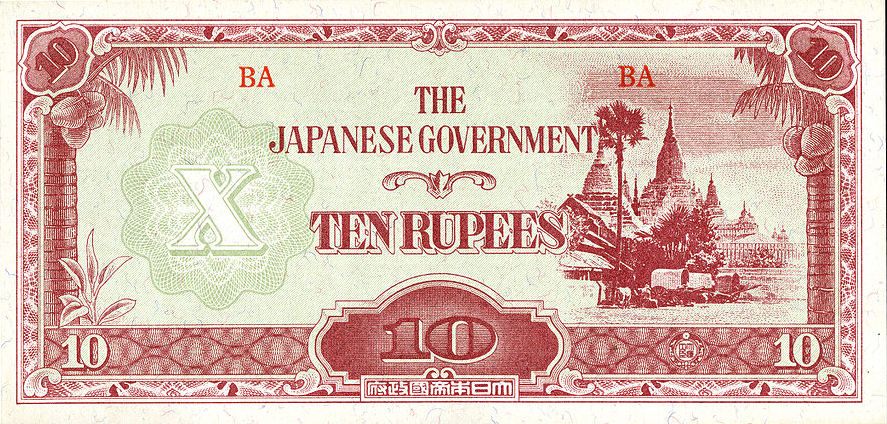

This is the 10 Rupee note that circulated in Japanese-occupied Burma:

(Image: National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History)

These territories have long since reclaimed their currency—and land—from Japan, but the banknotes, readily available on eBay, remain as tangible proof of the country’s aggressive wartime operations.

Update, 10/13: An earlier version referred to Hawaii as one of the 50 U.S. states—prior to 1959, Hawaii was a U.S. territory rather than a state.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook