Object of Intrigue: the Prosthetic Iron Hand of a 16th-Century Knight

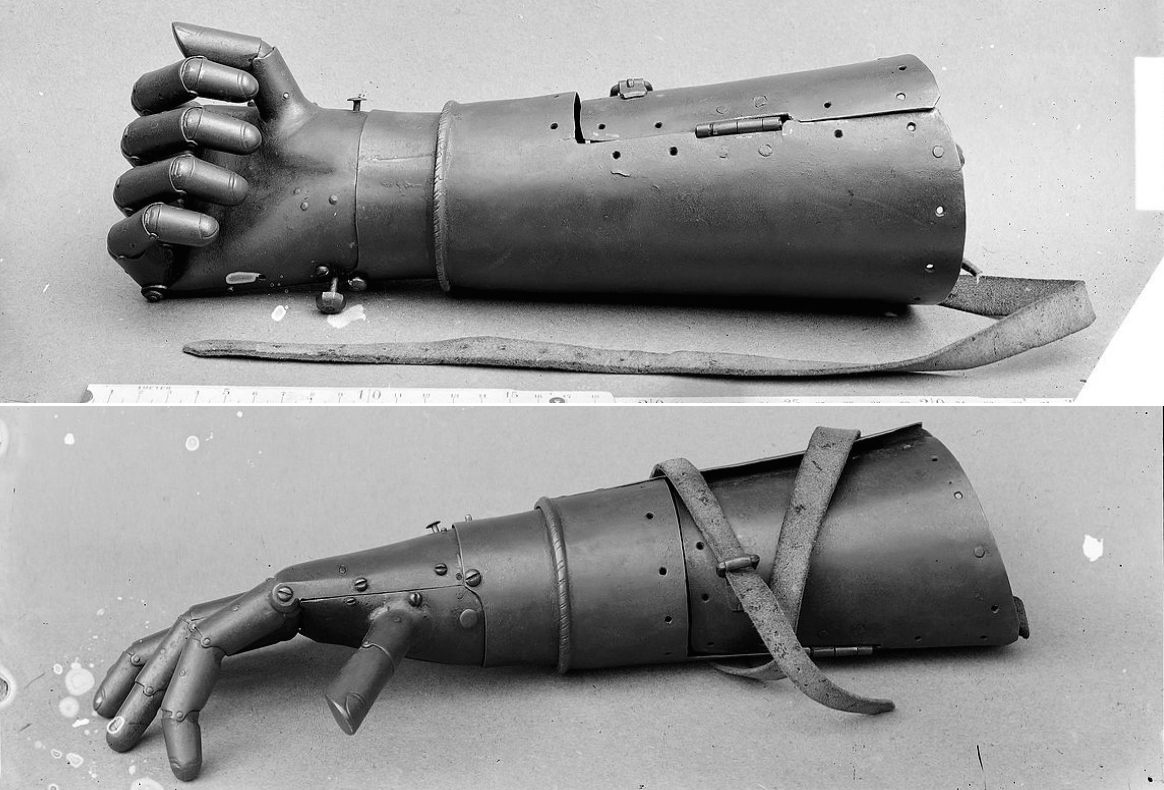

(Photos: Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg/Wikipedia)

Fierce German mercenary knight Götz von Berlichingen loved a good feud. As a soldier for hire in the early 1500s, he and his rogue crew of rabble-rousers fought on behalf of whichever Bavarian dukes and barons had the biggest beefs and the fattest wallets.

But all this battling came at a personal cost. In 1504, while fighting in the siege of the southeast German town of Landshut in the name of Albert IV, the Duke of Bavaria, the 23-year-old Berlichingen was hit by an enemy cannonball. Accounts vary over what happened next, but either way, it was dramatic—some say the ball hit Berlichingen’s sword, inadvertently causing him to cut off his own right arm. Others say it was the cannonball itself that robbed Berlichingen of his rapier-wielding appendage.

Regardless of the details, a hand was gone, and the knight had to find a new way to fight. The adjustment didn’t take long. Shortly after his unfortunate encounter with the cannonball, Berlichingen began sporting a clinking, clanking right hand made of iron.

Berlichingen’s first iron hand, made for him by an unknown artist shortly after the 1504 battle. (Photo: Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg/Wikipedia)

The first hand was a basic affair. Two hinges at the top of the palm allowed the four hook-like fingers to be brought inward for sword-holding purposes, but that was the extent of its motion. There was some attention paid to aesthetic detail, though, including sculpted fingernails and wrinkles at the knuckles.

Still, Berlichingen did not allow his newfound lack of manual dexterity to slow him down. He continued to lead his band of mercenaries in battle. His career, wrote Dr. Sharon Romm in an article on false arms in Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery, “consisted of fighting, gambling, and money lending,” for which he ”gained a reputation as a Robin Hood who protected the peasants against their oppressors.” Kidnapping nobles for ransom and attacking merchants for their wares was just part of the gig.

Berlichingen, left, in his standard “no time for your nonsense” mode. (Image: Archiv Burg Hornberg/Wikipedia)

After a few years of fighting with a serviceable yet inflexible false hand, Berlichingen upgraded to a superior model. His second iron hand, which extended to the end of his forearm and was secured with a leather strap, was “a clumsy structure, but an ingenious one,” according to the American Journal of Surgery.

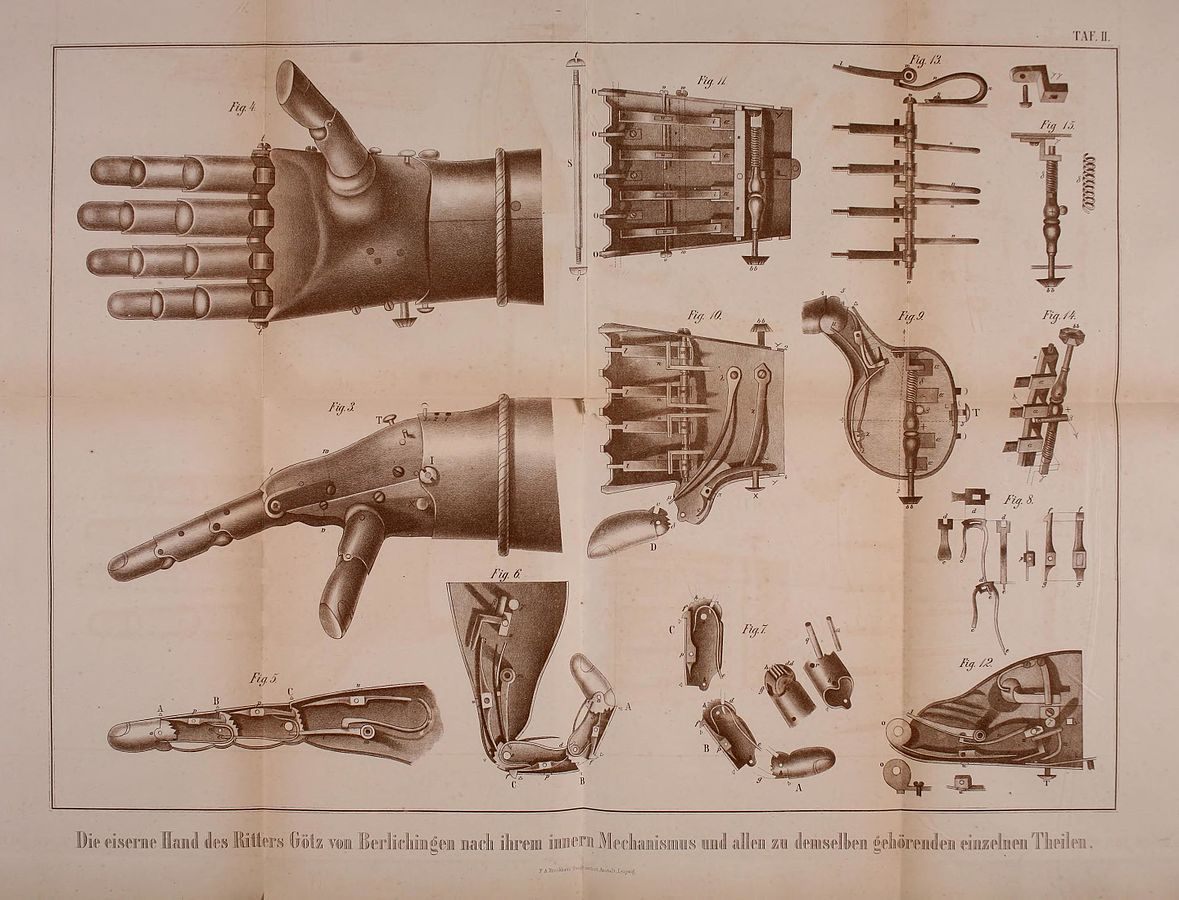

In contrast to the first hand, it was equipped with joints at each of the knuckles, allowing for a tighter grip. Berlichingen could use his left hand to maneuver the fingers of his right one, so they could hold a sword, quill, or the reins of his war horse. Spring-loaded mechanisms inside the hand locked the fingers into place, in a manner similar to the ratchet-and-pawl system used in handcuffs.

A 19th-century engraving shows the inner workings of the second iron hand. (Image:

This second hand, a rare example of a 16th-century prosthetic limb, is still kept at a castle museum in Berlichingen’s native Jagsthausen, a small German town of about 1,600 people. As a show of local pride in the defiant knight, the town’s coat of arms also features the iron appendage.

“Götz of the Iron Hand,” as he became known, kept fighting until the age of 64, participating in campaigns against the Ottoman Empire and in the 1544 Imperial invasion of France. He eventually retired from professional antagonism and penned an autobiography, which he left in manuscript form when he died in 1562, aged 82. Published in 1731, the autobiography inspired one Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who in 1773 wrote Götz von Berlichingen, a dramatic play based on Berlichingen’s life.

“His protection of the Peasantry around him, and the unbounded popularity which he enjoyed among them, as well as his frequent acts of violence, had made him particularly obnoxious to the princes and nobles,” reads the preface of an 1837 English translation of Götz von Berlichingen. The play uses much poetic license and transforms Berlichingen into a tragic figure who dies young. The knight is depicted as a ferocious yet sensitive soul. Explaining to a friar why he must greet people by offering his left hand to shake, he says: “My right, although useful in war, is insensitive to the touch of love; it is disguised by a glove; you see, it is made of iron.”

The plaque in Weisenheim am Sand. (Photo: Immanuel Giel/Wikipedia)

The most memorable line in the play, however, comes from an apparent real-life response offered by Berlichingen when he was under siege at Jagsthausen Castle. Ordered to surrender, the knight responds with ”Er aber, sag’s ihm, er kann mich im Arsche lecken,” or, roughly, “Tell him he can kiss my ass.” This then-uncommon phrase is now known among Germans as the Swabian Salute.

A plaque in the country’s southwestern municipality of Weisenheim am Sand displays his immortal words beneath a relief portrait of Berlichingen holding his iron hand to his heart and contemplating his next sponsored squabble.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook