The History of Passport Photos, From ‘Anything Goes’ to Today’s Mugshots

People have always hated how they look in them.

Face the camera directly. Wear the clothes you normally wear—no hats, no headphones, no glasses. (If you can’t take off your glasses, you’ll need a doctor’s note. If your religion necessitates some kind of head covering, you’ll need a signed statement.) Eyes open. Neutral facial expression or, perhaps, a so-called “natural” smile. And—click!

These regulations, among others, rule the American passport photo. They differ a little from country to country, however: New Zealand’s is still black and white, while Mexico, India, and the United States are three of the only countries that use a square aspect ratio. A grim-faced expression, required in the United Kingdom since 2004, helps facial-scanning software make matches.

But it wasn’t always this way. Though passport photos have been in place in some countries since 1914, most initially had no regulations at all, says Martin Lloyd, author of The Passport: The History of Man’s Most Travelled Document. “Its adoption seems to have caught the authorities by surprise,” he told the BBC. “They made no rules on how to pose for a picture. They were simply asked to send one in. So they did.”

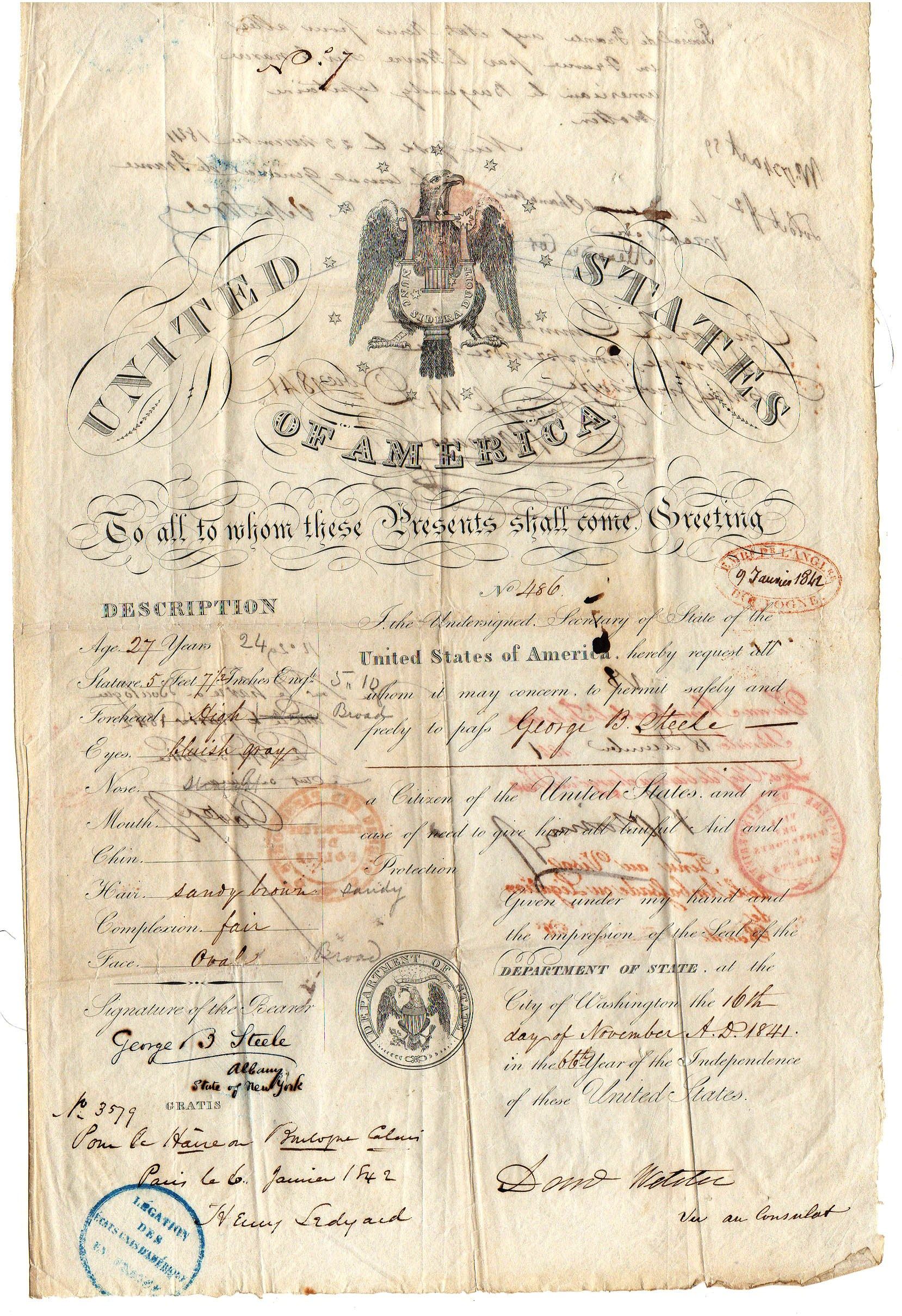

Photo-based identification had a somewhat unusual start, at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. In the wake of admission problems with similarly colossal exhibitions in London and Paris, Philadelphia introduced “the photographic ticket” for exhibitors and other free-pass holders. Each ticket had a number, the name of the holder, and a stamped photograph. This now-quotidian form of identification was a totally revolutionary, radical idea—so much so that it wasn’t until decades after their inception that photographs became standard practice on passports.

Before that, they listed distinguishing features, such as the shape of your chin or the color of your eyes. “I don’t know how you could understand that the person in front of you is the one written in the passport,” says Neil Kaplan, an Israel-based passport collector who’s been amassing the documents for almost three decades. Kaplan also blogs about his collection and has a large Twitter following.

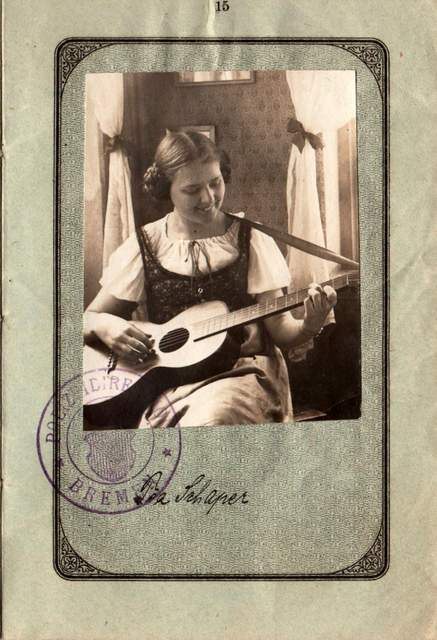

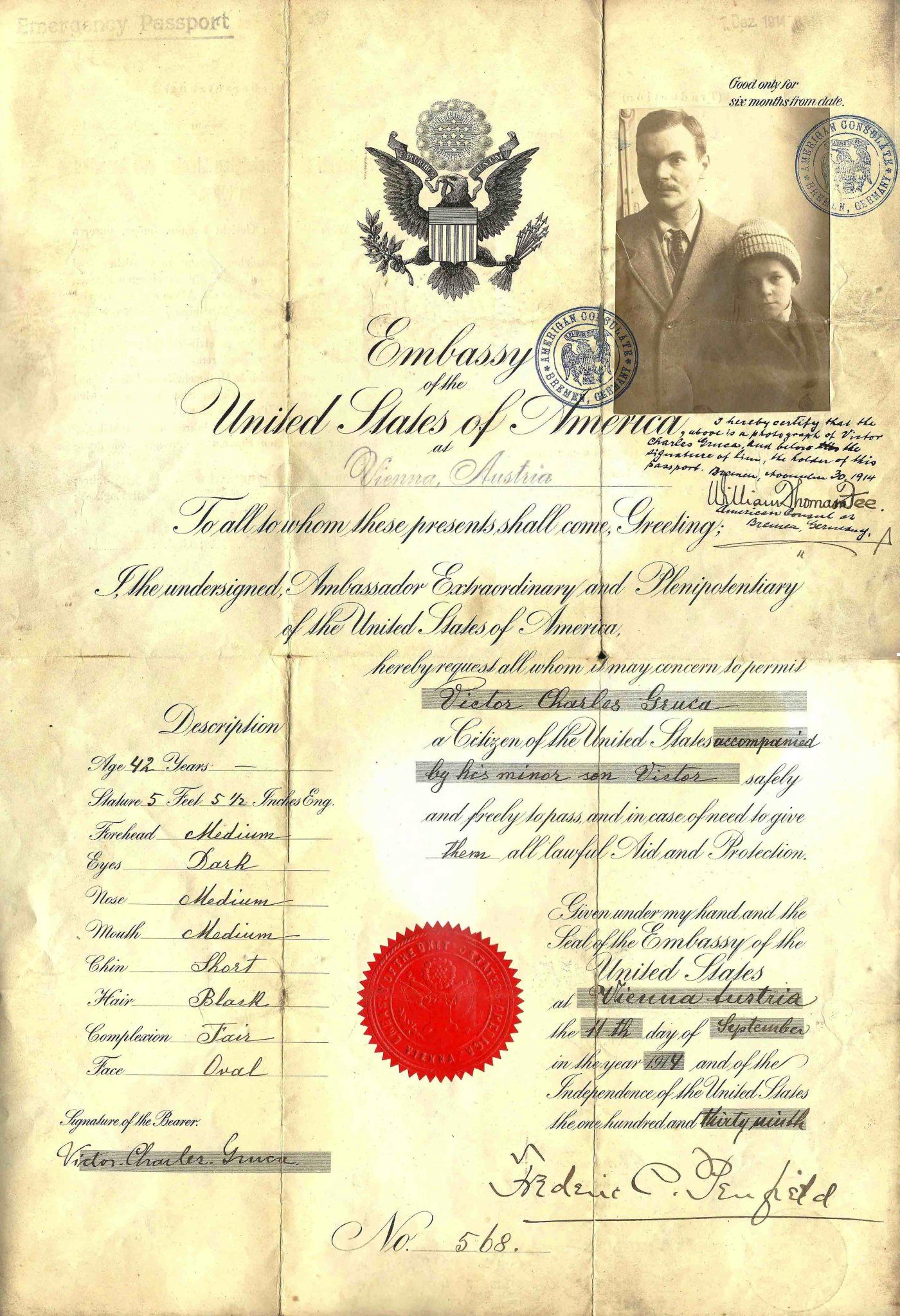

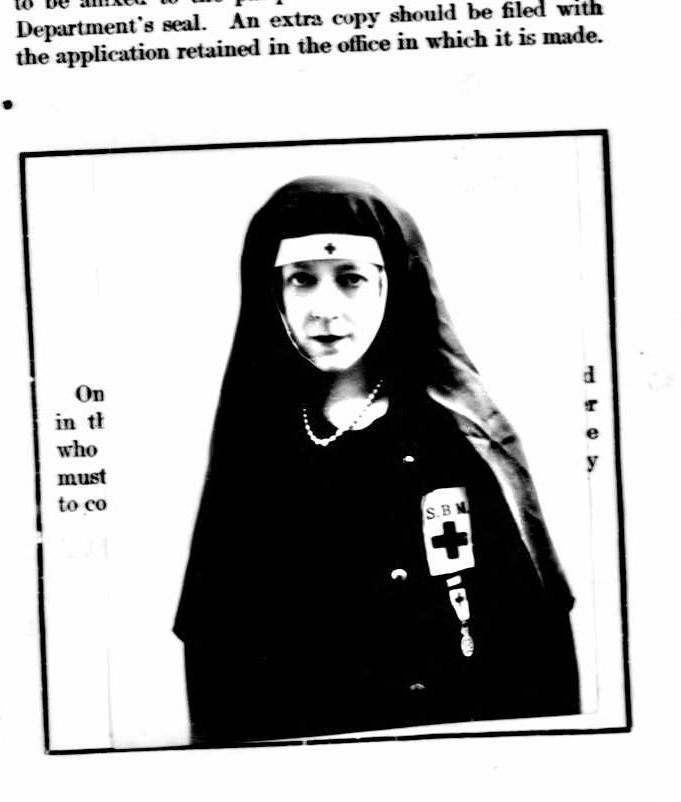

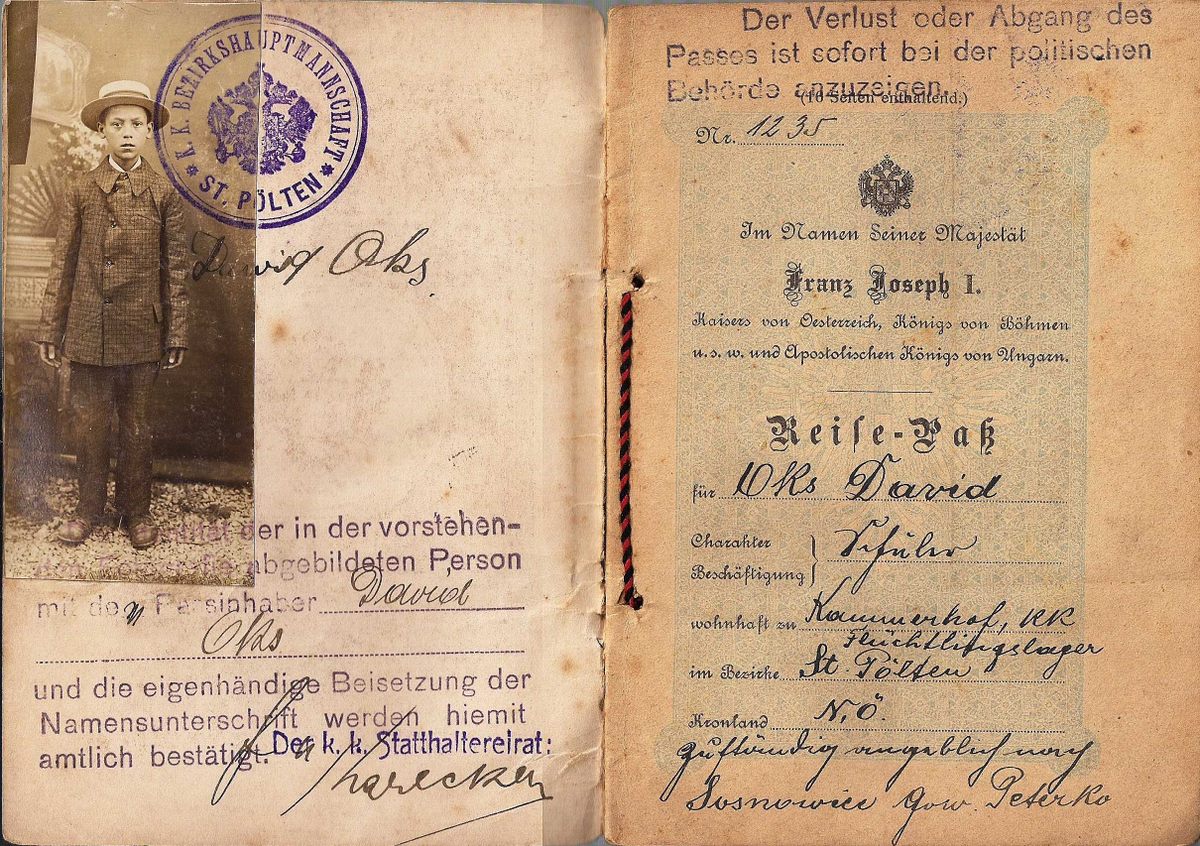

Compared with today’s high level of standardization, early passport photos didn’t appear to have many rules at all. Images might be cut out of group photos, show people decked out in full religious garb or a hat, or even be portraits of people doing the things that they loved. Others were transplanted from one document to the next, stamps and all. Sometimes, Kaplan says, this was because some people were frightened to leave the house to have a photograph taken—refugees, for example. Alternatively, passport holders may not have been able to afford new photographs. (In 1929, in New York, the fee varied from between the equivalent of $10 and $30 today, plus the cost of the passport itself. Together this would be close to $200 in today’s dollars.)

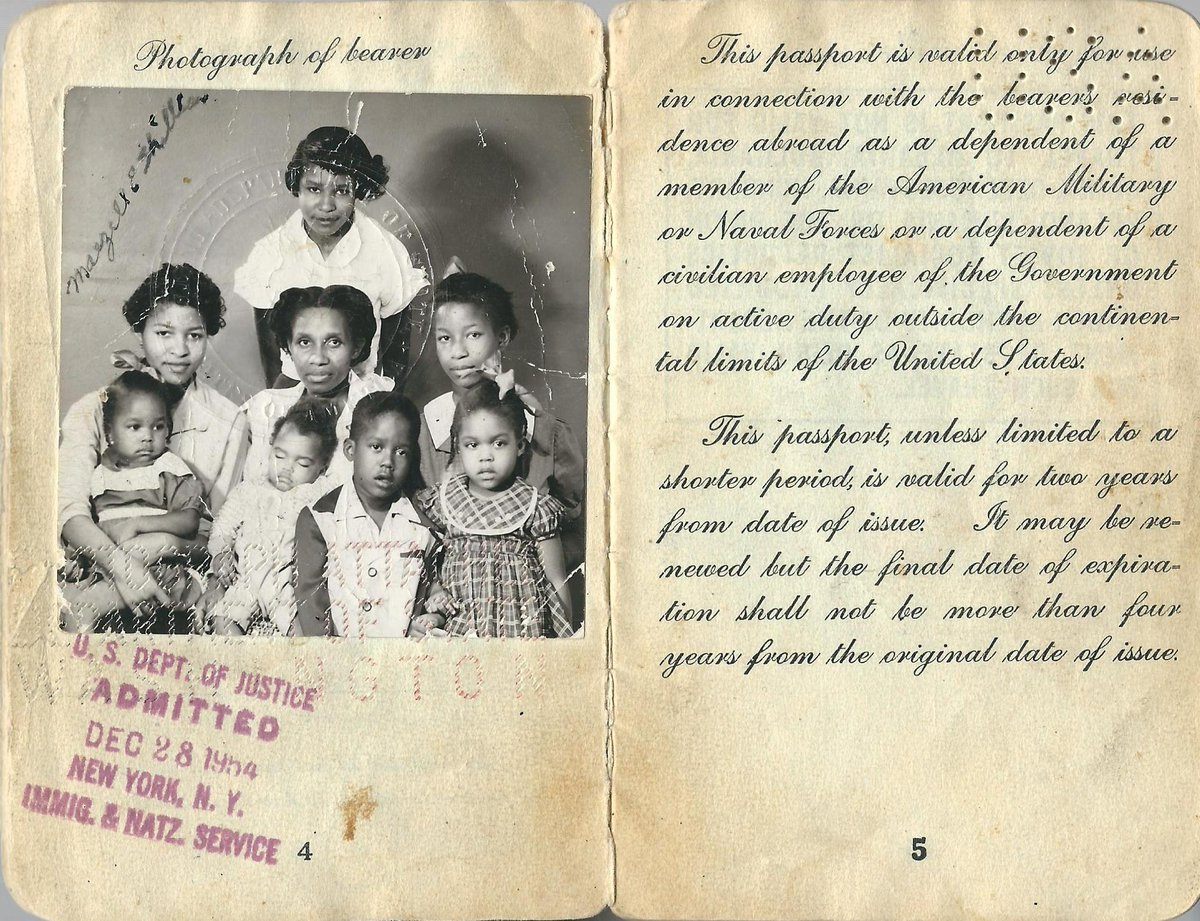

The notion of a single passport for a single person was also a later one. Deep into the 1930s, married American women were footnotes in their husband’s passports, listed simply as, “Mr. John Doe and wife.” Single women were entitled to their own passports, which they could use to travel alone, while married women could not use the document without a husband present. This practice continued, despite the efforts of women’s rights advocates, until 1937, when the State Department issued a memo explaining that “because our position would be very difficult to defend under any really definite and logical attack, it seems the part of wisdom to make the change.”

Family passports did continue to exist under particular conditions as late as 2012 in the United States. (And there are still some countries that will permit children to be part of a parent’s passport.) This caused problems with photography, however: The New York Times described the difficulty of fitting all the faces into one frame “of not more than 3 by 3 inches. One such family reported five unsuccessful attempts to fulfill this official requirement.” Picture an entire family squeezing into a photo booth—minus the joy.

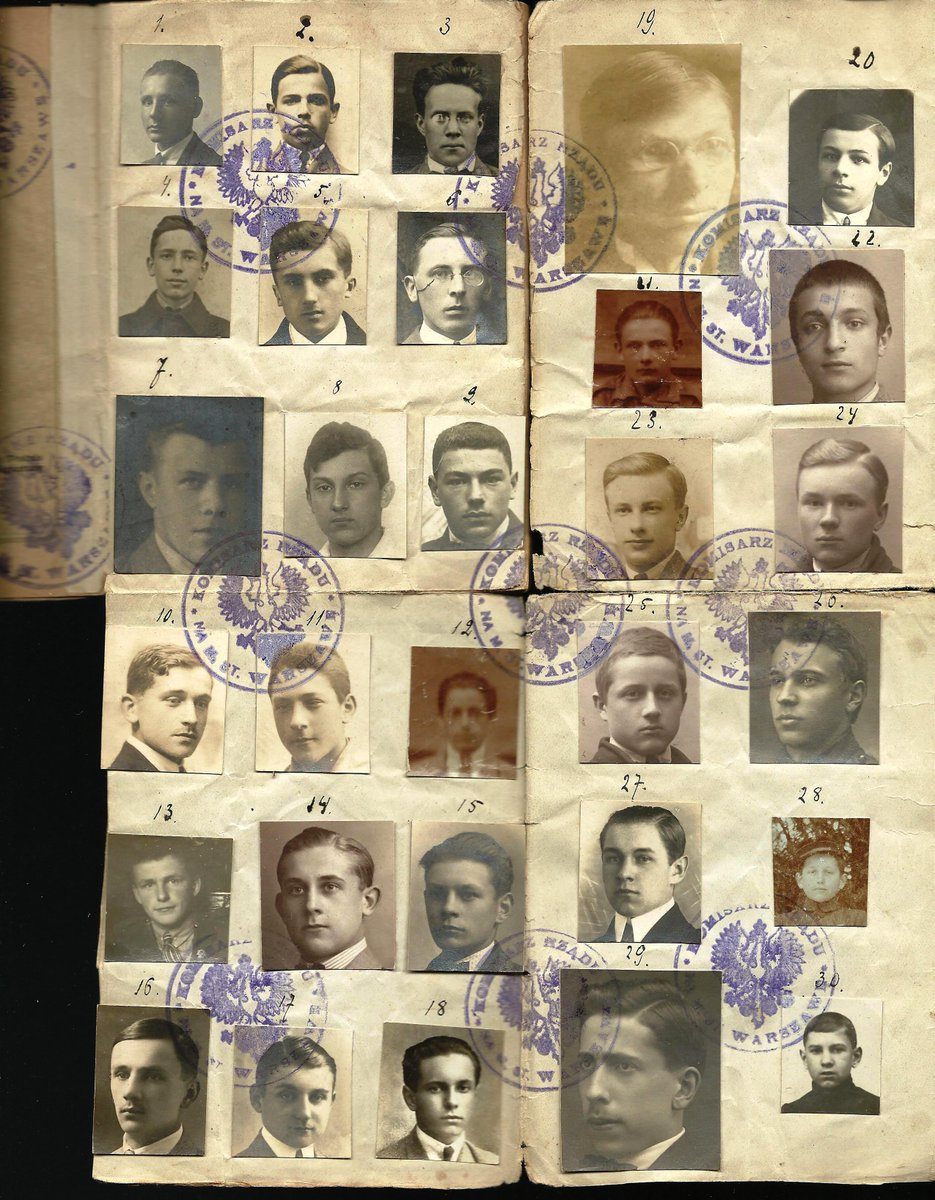

Rarer still are collective passports, where as many as 20 faces were affixed to the same sheet. “Usually, they all traveled together with one or two group leaders, who would have the collective passport,” Kaplan says. These were especially common for groups of refugees requiring swift evacuation, such as Jews escaping the pogroms of Eastern Europe, or leaving Germany for the United States in the 1920s. Other examples include Polish worker groups seeking employment in France or sports teams attending international events.

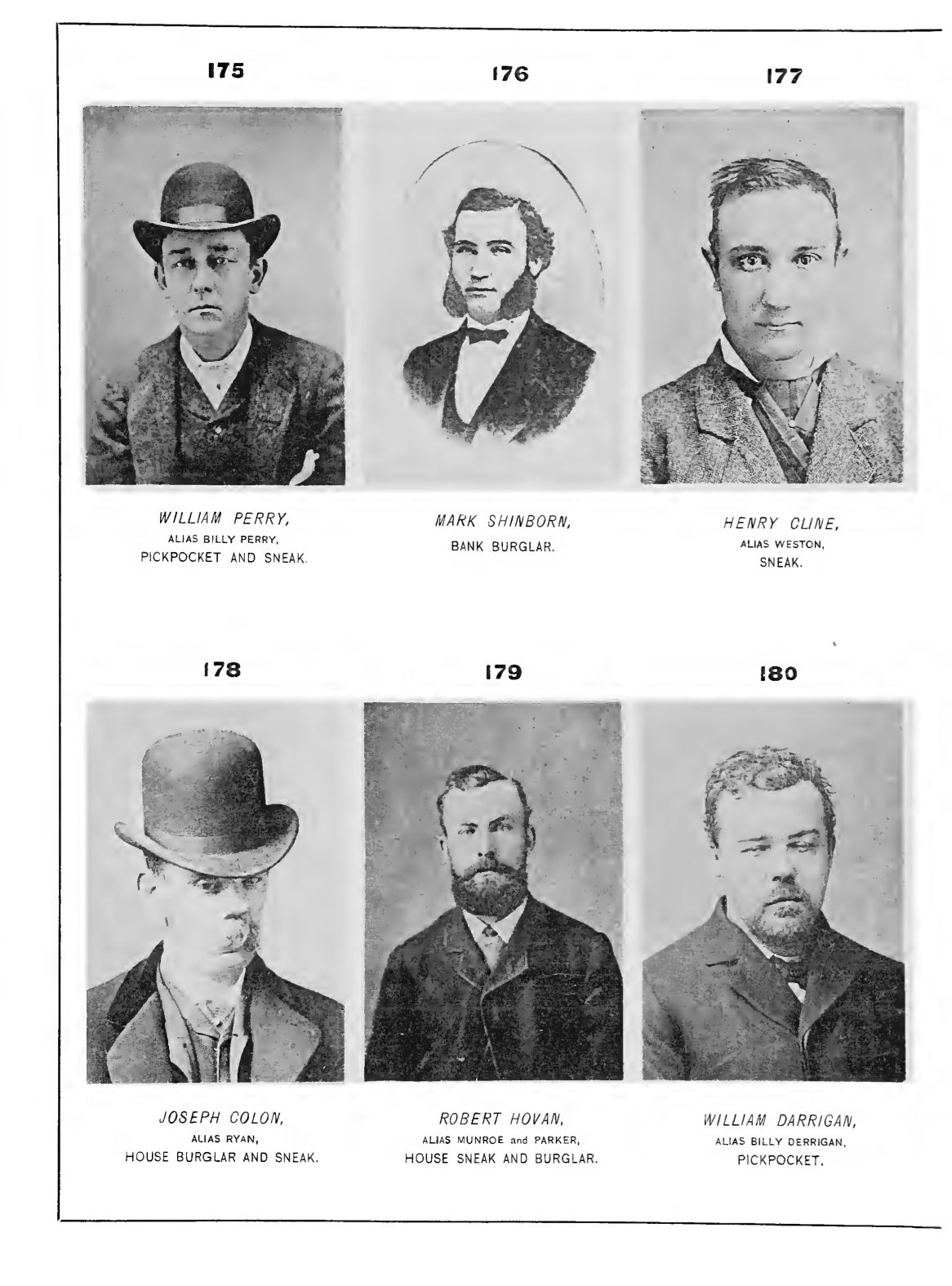

But, from 1920, the worldwide, individual passport standard began to emerge and develop, and what had been thought of as an emergency document (outside of times of crisis, passports weren’t always strictly necessary for international travel) became a permanent fixture. This coincided, in the United States, with regular steamship travel to Europe—passport required. Perhaps surprisingly, people seem to have felt threatened by the standardization of the passport photo. The stark, frontal, “mugshot” style reminded many of images of criminals and ruffians from “rogues’ galleries” circulated as a form of entertainment.

Moreover, says Craig Robertson, author of The Passport in America: The History of a Document, middle- and upper-class people found the idea that they would need to prove their identities somehow morally affronting. “It’s like, ‘Look at me, I’m white, I’m upper-middle class, I’m dressed well, I’m not a suspicious person, I shouldn’t be the target of any form of identification document,’” says Robertson. This was a time before documentary infrastructure, and there was genuine resistance to the idea of being reduced from a person to a legal paper. “The passport seems to have become the poster child for that,” he adds. “That if you’re a traveler and you can afford your cabin, you should not be part of the suspect population.” Passport photos, then, triggered an association with being recorded and requiring recording, which made some people deeply uncomfortable.

“If you think about it,” says Robertson, “if you’ve never had to present a document in any capacity and your word is always taken literally and figuratively at face value, to suddenly be asked for not only the passport but also all the supporting documents – it suggests you can’t be trusted any more.” In 1929, the New York Times described how bothersome this seemed to the privileged: “Foreign-born fare best. They are used to bureaucracy and documents which irk the native citizen.” In the 10 years before and after that editorial, Americans acquired personalized charge cards, drivers’ licenses, and, finally, social security numbers. All these developments gradually increased American official-document literacy and tolerance, as people became increasingly comfortable being represented by cards, papers, and records.

Even with acceptance, there remained a feature of passport photos that people have always disliked: the way they look in them. A New York Times editorial from 1930 seized upon this middle-class anxiety and described passport pictures as “notoriously unpleasant and unflattering. The mildest mannered man looks like a thug or a gunman, and a bright eyed miss becomes a heavy-featured half-wit. Few travelers ever feel anything but a pang of horrid surprise, almost disbelief, upon first looking at the photograph which is to identify them in a foreign country.” Even celebrities, they said, who might ordinarily appear beautiful, amiable, or “generally attractive,” have a “criminal or imbecile cast of countenance.”

A passport, says Robertson, creates an identity that we have to prove matches our own. On the face of it, it seems peculiar that a glowering, unflattering mugshot should be made to represent who we are better than, say, a smiling portrait, a glamour shot, or a photo of one playing the guitar. The document may say, “This is who I am,” but it does so the most depersonalizing way possible.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook