Steampunk… Or Just Punk’d?

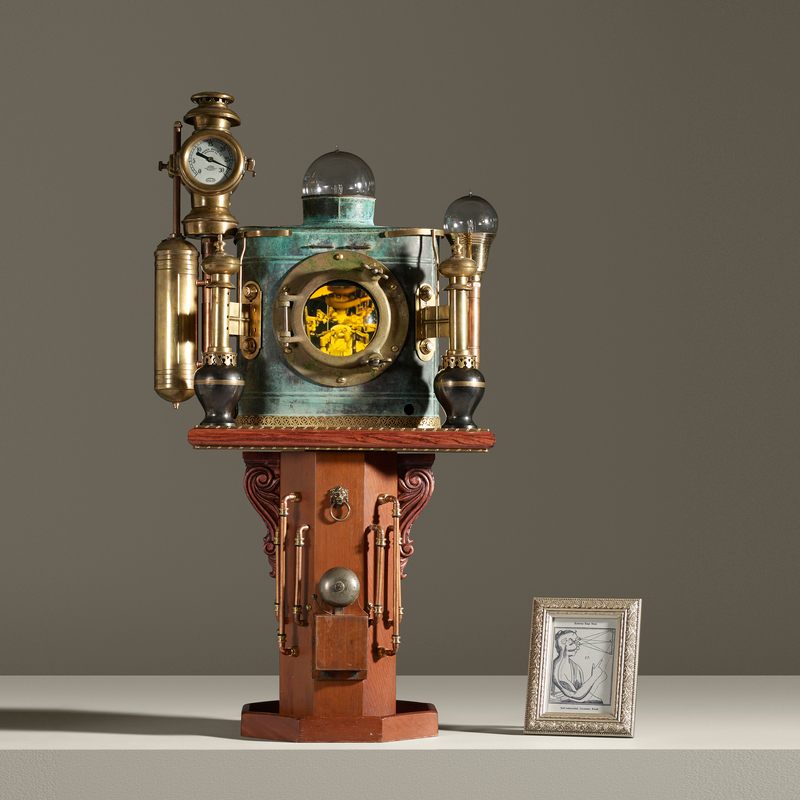

The Periscope machine captures a viewer’s likeness and displays it on the top monitor.

The Periscope machine captures a viewer’s likeness and displays it on the top monitor.

(All photos courtesy of Wright.)

When film editor and Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) professor Burton J. Sears died in August 2014, he left behind a collection of mysterious machines purportedly created during the 19th century, including the Periscope. On April 16th, all of 11 of the steampunk-style contraptions go up for auction at Wright in Chicago.

While potential buyers have been dazzled by the aesthetics of Professor BJ Sears’ Technological Rarities, many are a little confused by their backstories. And with good reason.

Take, for example, Reddington’s Phonelescope, pictured below. According to Sears’ explanatory notes, the machine was built by a mining engineer named Whispering Jack Reddington, who graduated from the Colorado School of Mines in 1899. Sears wrote that Reddington, a deeply religious man, was fascinated with the transmission and amplification of sound waves, and believed that the dynamic range of the human voice was divine.

“The scientific beliefs of the day were that light waves, like sound waves, needed a medium for transmission,” wrote Sears. ”Jack spent all his off-hours trying to alter what was called the luminiferous aether (‘aether wind’) that carried them. This was in complete contradiction to the early Michelson-Morley experiments. Jack’s belief was that using different wavelengths of light in the presence of the divine sound could slightly alter the aether itself and thus produce sounds never heard by man before.”

Reddington’s Phonelescope, one of the 11 mysterious machines up for auction.

According to Sears, Reddington conducted several unsuccessful sound-wave experiments in the nooks and crannies of a Colorado mine, resulting in cave-ins that saw the man relieved of his duties and banned from the premises. ”Reddington’s Phonelescope,” wrote Sears, “is the only surviving machine from Jack’s ill-fated experiments.”

It’s a fascinating story. It’s also not real. Well, not all of it—the Colorado School of Mines exists, as does the concept of luminiferous aether. The Michelson-Morley experiments did take place during the 1880s. But Whispering Jack Reddington was a man who lived only in Professor Sears’ imagination. Sears built all 11 of the mysterious machines himself between 2009 and 2014.

Sears’ confluence of mythology and reality, which is found in the backstories he wrote for the machines up for auction, is one of the reasons Wright auction specialist Peter Jefferson decided to take on Professor BJ Sears’ Technological Rarities. “It is a little bit outside of what we’re normally selling,” he says, “but I thought it was the perfect melding of three things: science, history and art.”

The Electrophonic Anachroscope, which is equipped with an inscrutable time-travel function.

The Electrophonic Anachroscope, which is equipped with an inscrutable time-travel function.

Sears, whose film editing credits include the features Jacob’s Ladder, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, and Henry and June, built the steampunk-y machines out of scraps he found on his travels. “He was always fascinated by the World’s Fair, new discoveries, expositions, underground transportation, underwater transportation, all of these things,” says Jefferson. “It fascinated him to collect and gather these objects that are old and have their own stories and backstories and histories.”

During summers when he was teaching at his school’s campus in Lacoste, France, Sears would browse flea markets and yard sales for pipes, dials, gauges, and other debris from the distant past. After shipping them back to his Savannah home, he began to assemble the pieces into machines. As he built each piece, he constructed a plausible history to go along with it. Having spent three decades in the film industry, Sears was adept at melding truth and fiction.

“The stories are just really compelling, and it makes you wonder what it is that you’re really looking at,” says Jefferson. “I had someone come in yesterday to drop off something unrelated and the person was asking me, ‘So, these are all re-creations of objects that existed?’ He was convinced that these things were actual replicas.”

It’s an understandable belief. One of the machines, the Sinehouse Archive, is described as “a replica of a device made in the summer of 1860 by Dr. Wolfous Sinehouse.” Plausible so far, but read a little further and you’ll discover that Sinehouse, a man dreamed up by Sears, was apparently the leader of a highly controversial utopian separatist community with strict rules. (“To better bathe in the glow of their creator’s majesty,” Sears wrote of the community, “the members kept clean-shaven heads and never wore hats of any kind.”) Sinehouse is said to have used these community members for his own mysterious experiments.

The history of the Sevastopol Travel Clock, pictured below, is similarly truth-adjacent. According to Sears, the device was ”abandoned by Major General Adolphus Tull of the Grenadier Guards and was found on the battlefield, in September 1855. Contrary to Florence Nightingale’s reports of horrendous living conditions in the Crimea, this clock may be evidence that some in the officer corps soldiered on.” Sears helpfully noted that “the clock doubled as a tea pot.”

The Sevastopol Travel Clock

The Sevastopol Travel Clock

It’s not just the backstories that are surprising: these machines combine history and technology in unexpected ways. Six of the devices incorporate concealed iPhones, which are used to run looping video and audio. “They’re hidden in compartments or drawers inside of encasements or on the furniture that the piece rests on,” says Jefferson. “He built little trap doors that are hinged or completely hidden and isolated. You wouldn’t know—unless you knew.”

Professor BJ Sears’ Technological Rarities are auctioned on April 16, 2015, from noon CST at Wright in Chicago and online. Price estimates range from $10,000 to $30,000.

The Mills Device, purported to have been built in the 1850s.

The Satellite Monitor, a companion piece to the Anachroscope.

The Cartesian Kiosk, an ode to the invention of the light bulb.

The Lyndhurst Unit, said to have been discovered in a country house on the Hudson.

The Lyndhurst Unit, said to have been discovered in a country house on the Hudson.

The Muybridge Experiment, which features video of a galloping horse.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook