Most American Cities Once Had Red-Light Districts

But they didn’t last long.

In February, in San Francisco, the City Attorney accused the owners of a business on Kearny Street of running not, as advertised, a massage parlor but a “place of prostitution, assignation, and lewdness.” When visiting Queen’s Health Center, the city wrote in its legal complaint, investigators had seen workers half-dressed or fully naked, and undercover officials were offered sexual options ranging from blow jobs to group sex. The most unusual feature of the suit the city filed against Queen’s Health Center, though, was its legal basis: it alleged that the business had violated the California Red Light Abatement Law, which was passed more than a century ago.

The Red Light Abatement Law hadn’t been used in an effort to stop sex work for decades: the City Attorney’s office noted that its suit that this represented “the first time in recent history” the city had tried to use the 1914 law to shut down a place of prostitution. In the years before World War I, though, this same law was used to shut down dozens of brothels located just a few blocks from Queen’s, in San Francisco’s Barbary Coast neighborhood, one of many red-light districts operating in U.S. cities in the early 20th century.

Until the early 1900s, it was common for American towns and cities to have a red-light district filled with saloons, dance halls, brothels, and other venues that offered a continuum of indulgences in intoxication and sex. San Francisco had three—the Barbary Coast was the most famous—but, starting in the 1890s and ending in the 1910s, across the country cities large and small segregated their “sporting class” into neighborhoods designated for scandalous behavior. The United States’ red-light districts were a blip in American city planning, a well-intentioned policy that failed to achieve its intended goals. Originally conceived by reformers and planners hoping to centralize vice, these districts were swept away in one short decade with a well-executed campaign to pass “red light abatement” laws in cities and states across the country.

“It’s a moment of city planning when people were trying to create pragmatic and moderate responses to what we’d now call victimless crimes,” says Mara Keire, a lecturer at Oxford and the author of For Business and Pleasure: Red-Light Districts and the Regulation of Vice in the United States. “It might have continued, except the federal government shut the red-light districts down.”

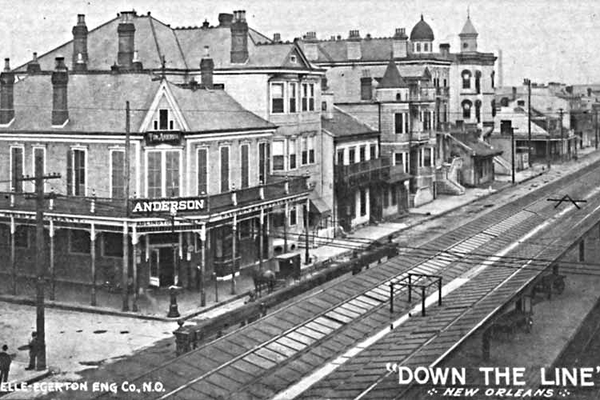

America’s most famous red-light district might be Storyville, New Orleans, a rectangle of blocks just upriver from Congo Square, where, starting in 1897, prostitution was legal. But New Orleans wasn’t the only place that used city ordinances to define the boundaries of vice. In Shreveport, Louisiana, and in a few Texas cities, city councils passed similar laws. Most cities, though, didn’t bother with official limits; as Keire writes in her book, police officers and judges would use selective enforcement to gather “the sporting class” into particular places.

The rise of red-light districts in the 1890s didn’t happen by accident. These policies, “a distinctly American phenomenon,” writes Keire, were pushed by “mugwump” activists trying to break the connections made between working class people and Democratic political machines at neighborhood saloons and dance halls. Victorian-era reformers believed that it would be impossible to eradicate these establishments altogether, but by confining them to certain areas, vice could be segregated from the rest of the city and controlled. For a modern city, a red-light district was “a necessity like a sewer,” as one reformer once said.

The strategy, though, had the opposite of its intended effect: instead of containing a city’s more ribald instincts, these economic clusters strengthened the drinking, drugs, and sex industries. Since they were located downtown, red-light neighborhoods often blended at the edges into the more respectable parts of the business district. As Keire puts it, “geographic confinement did not equal cultural containment.”

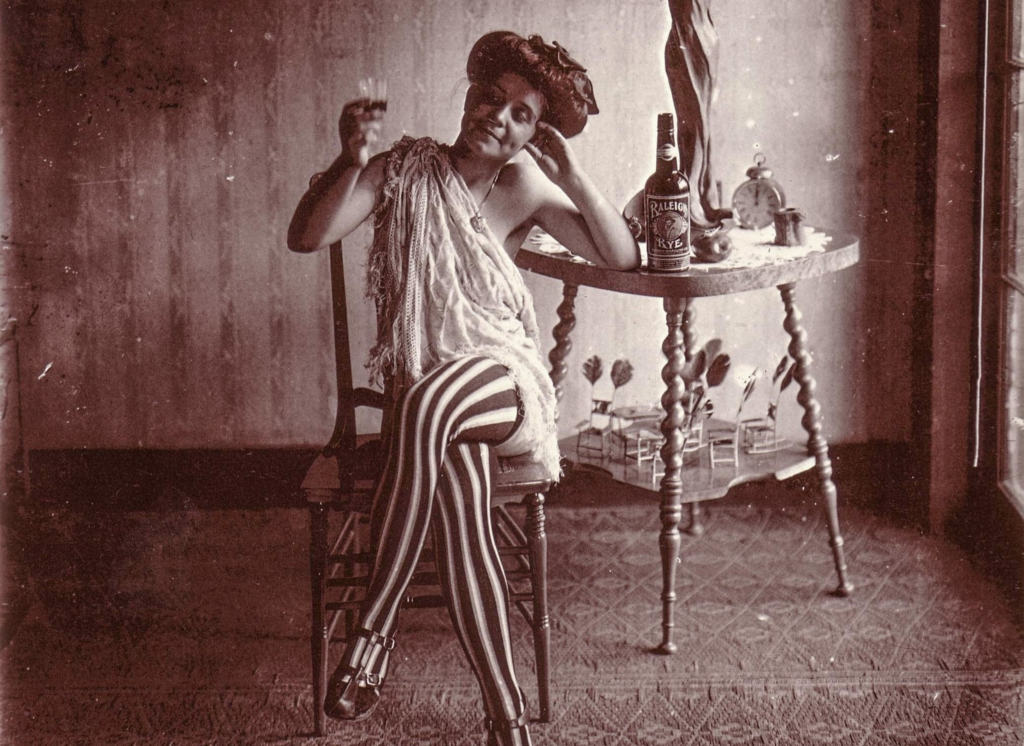

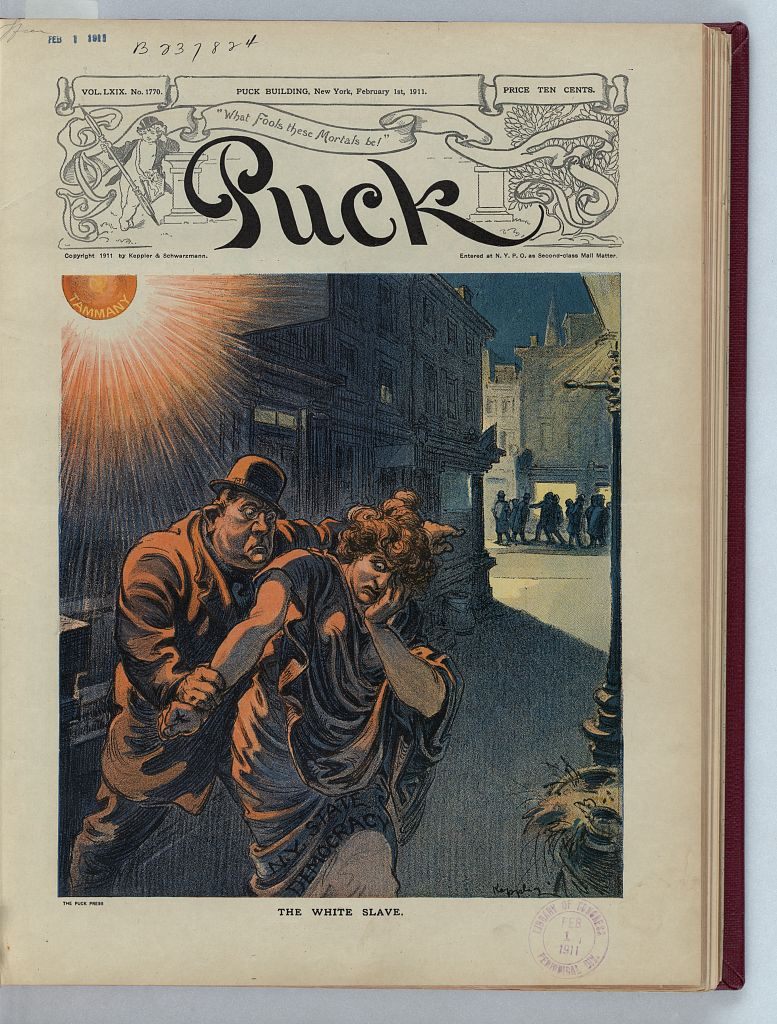

By the turn of the century, a new class of reformers started taking a different view toward urban vice—that it was dangerous and should be eradicated. Sex workers were recast, from no-good, disgraced women to innocents lured into a life of evil. They starred in an increasingly popular narrative about “white slavery,” in which young women were said to be kidnapped or coerced into working as prostitutes and kept in bondage through debts supposedly owed to their madam. It’s hard to know exactly what the experience of every women at the time was, but it’s clear these stories relied on heated rhetoric for effect. “There was some evidence of coerced prostitution during this period, but very little,” writes the lawyer Peter C. Hennigan, in an article on the abatement laws. Some women likely were exploited economically and kept in debt, but that was true in other industries as well; if venereal disease was a risk, there were severe occupational health hazards in factories and sweatshops, too, Keire points out. “I like to give the woman the benefit of the doubt,” she says. “They were making rational choices, and some were able to get out of it.”

These stories, though, helped turn public opinion against the red-light districts, and early in the century, Progressive reformers started organizing a campaign to eradicate such neighborhoods. The first Red Light Abatement Law passed in Iowa in 1909, and by 1914 the American Social Hygiene Association was working to pass similar laws state by state. As Hennigan shows, the reform organization had a model abatement law that legislatures could use as the basis for anti-vice reforms, as well as a strategy for defending the laws when they were challenged in court. Local governments could even hire ASHA’s investigative team to report on the state of vice in their cities.

Abatement laws made it possible for almost anyone to bring a nuisance complaint against a place where prostitution was taking place; they didn’t regulate the behavior of people, but the use of buildings. That meant the most powerful opponents of such bills were often from the real estate industry, which benefitted from the high rents vice businesses could pay. But the reformers had won over the public. By 1916, ASHA could list 47 cities that had shut down red-light districts; a year later, the list had grown to 80. By 1919, 41 states had passed red-light abatement laws. The campaign against vice districts, Hennigan writes, was “the most successful use of public nuisance law in American history.”

The above map shows the locations of businesses operating in San Francisco’s Barbary Coast red-light district circa 1908. (Source: The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco)

As the red-light districts were shut down, the women who worked there moved to more tolerant cities or made their businesses more mobile and secretive. For the people who ran brothels, in particular, the campaign against red-light districts was financial devastating; after telling the local police chief to “go to hell,” one madam in Atlanta committed suicide, writing that she had “nothing left to live for.”

Although sanctioned red-light districts continued on in some cities, including San Antonio, Texas, and Butte, Montana, vice districts died in most places in the U.S. after the federal government put its muscle behind abatement laws as part of the war effort. Soldiers didn’t need to be distracted by sex or laid low by venereal disease. A century later, this experiment in American urban districting has mostly been forgotten.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook