Retracing the First, Forgotten Motorcycle Ride Across America

George Wyman took 50 days to get from San Francisco to New York in 1903.

George Wyman, with his bike, ready to head east (Photo: Public domain)

When George Wyman crossed the Nevada desert in 1903, on a 1 ¼ horsepower motorcycle, he mostly rode on railroad tracks. It was a bumpy ride, but the sand that surrounded him was too soft too ride his bike over. Once, there had been wagon tracks here, but often the railroad ties lay right on top of them. This was the shortest and clearest route across the west.

No one had ever traveled across the country in a motorized vehicle, and Wyman intended to be the first. At 26, he was a champion racing cycler and had already circumnavigated Australia on a bike. The summer before, he had become the first person to cross the Sierra Nevadas on a motorcycle. His California Moto Bike was essentially just a bike frame with a motor attached, but as he crossed the mountains, he had an idea. He could ride that bike straight across the country.

Wyman left San Francisco from Lotta’s Fountain on May 16, 1903, with a promise from Motorcycle Magazine to publish an account of his journey. Fifty days later, he rolled into New York City. His bike was so busted that he had to pedal the last 150 miles, but he had made it: he was the first person to motor across the country.

Just 20 days after he arrived, though, Horatio Nelson Jackson completed the same journey in a car. Jackson’s cross-country trip had taken longer than Wyman’s—Jackson and his two companions (one human, one canine) had traveled 63 days from west to east. But that didn’t matter. The car captured the American imagination in a way bikes never had, and for decades, Wyman was almost completely forgotten.

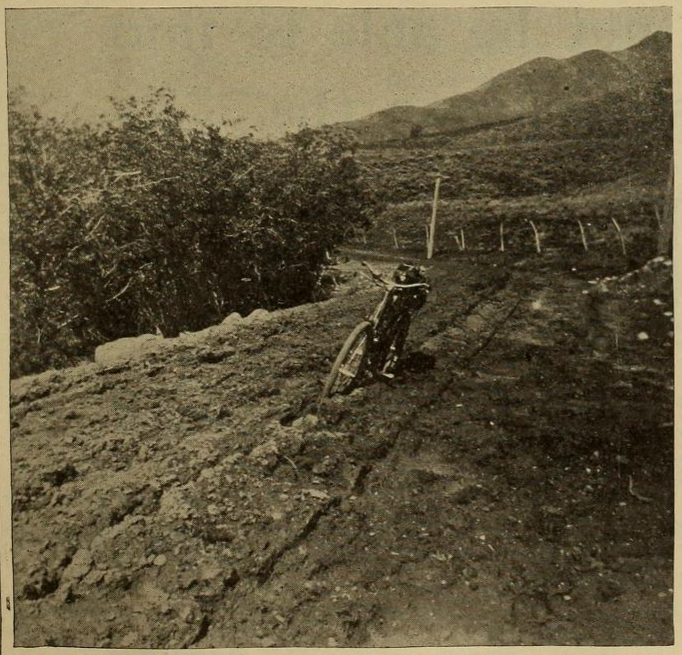

Wyman’s bike stuck in the sand (Photo: George Wyman/Motorcycle Magazine)

A few years ago, though, a small group of long-distance motorcycle riders discovered Wyman’s legacy and resolved to bring it back to life.

“He is to the long-distance riding community what Charles Lindbergh is to general aviation,” says Tim Masterson, the president of the George A. Wyman Memorial Project.

Long-distance riding is roughly analogous to ultra-marathoning: it is about endurance, over distances that most people would blanch at. To become a member of the Iron Butt Association, an organization dedicated to the sport, one can ride 1,000 miles, roughly the distance between Boston to Atlanta, in 24 hours, or participate in the Iron Butt rally, which covers 11,000 miles in 11 days. To Masterson and like-minded riders, George Wyman was the first of their kind.

Since 2014, the memorial project’s members have been working to mark Wyman’s route across the country. Their goal is not just to have people recognize his ride but to recreate it, passing through the same places that Wyman did.

His route took him almost straight across the country, through Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming, across Nebraska, Iowa, and Illinois, from Chicago, through Buffalo, N.Y., to Albany, where he turned south and rode through the Hudson Valley to New York City. He covered approximately 3,800 miles, and there was no part of that trip that was easy.

Masterson likes to tell other long-distance riders that if they read Wyman’s account of his journey, they will find in it every hardship and every exhilaration they’ve ever felt in a long-distance ride.

A 1903 motorcycle, though not the brand Wyman rode (Photo: Yesterdays Antique Motocycles/CC BY-SA 2.5)

Wyman described the road on the second day of his ride, out of Vallejo, California, as “a succession of land waves, one steep hill succeeded by another.” The wind blew so hard that he had to break the muffler off the bike’s engine to give it enough power to keep going. That same day, he smashed his first cyclometer in a fall—he would go through at least three more, and because they kept breaking, he would never know exactly how many miles he covered during his trip.

As soon as he passed over the mountains, he was in the desert, and within a couple of days, he was “tired of sand and sagebrush and railroad ties.” On a muddy road up Battle Mountain, after having to walk his bike for 10 miles, he made a promise to himself: “I would not ride a bicycle through Nevada again for $5,000.”

In 1903, American transportation was in the middle of a transformation. Cyclists in the Good Roads Movement were advocating for better intercity roads, but it was still more than five years before Michigan built the country’s first concrete highway. Outside of cities, roads were still made of mud and gravel, and the train was still the fastest way to travel between cities. Trains came rarely enough, though, that Wyman could ride along their tracks without fear. For the first half of his journey, most of the places he stopped had just a scattering of buildings, built by the railroads to serve crews and passengers. He even caught sight of a few families still traveling in covered wagons.

Often, though, Wyman was alone, spectacularly so. On his third day, he describes crossing a high trestle bridge a few miles east of Sacramento. Think of him on his simple motorcycle, bumping along the railroad tracks, above the water, with the snow caps of the Sierras behind him. His description of Nevada’s Forty Mile desert, where hundreds of people and thousands of animals died trying to make it to California, could easily have come from a Cormac McCarthy character:

I might have been a pre-Adamite soul wandering in the void world before the work of creation began…I imagine myself to be the last of the race, who by some strange freak has escaped the blight that caused the end of the world…”

The Nevada desert (Photo: Michael Day/CC BY 2.0)

On his way east, Wyman spent so many miles jittering along on railroad ties that his lower back started to ache, but when he tried the roads, his bike would get stuck in the sand or mud. He started writing of the “hoodoo” that haunted his journey and threw away a vest to try to rid himself of his bad luck. In the Rockies, he forded cold mountain streams. In Wyoming he only found his way over a mountain by following a trail of hoof prints that then-President Teddy Roosevelt and his entourage had left there the day before.

“It was not a sentimental journey at any stage, nor a humorous one,” Wyman wrote.

By the time he reached Albany, the mud, the sand and the hundreds of miles of battering along the tracks had taken such a toll on the bike that the engine stopped working. This time, Wyman could not fix it. On July 5, he started pedaling up and down the hills of the Hudson Valley, and he kept riding all through the night. On July 6, in the afternoon, he reached New York City.

This is the journey, from San Francisco to New York, that as many as 50 riders will attempt this summer, in honor of Wyman. Although there are paved roads along his route these days, last year the Iron Butt Association officially established two George A. Wyman Memorial Challenge rides meant to capture the spirit of his journey. Over Memorial Day weekend, Masterson and other long-distance riders will meet in the San Francisco area, and together set off on one of the two routes.

For either ride to be certified by the IBA, the trip must begin and end between May 16 and July 6—the period of Wyman’s ride. One ride, the George A. Wyman Memorial Grand Tour, starts at Lotta’s Fountain and ends at 1904 Broadway in New York City, where the New York Motor Cycle Club once was located. In between, riders must visit as many of the memorial project’s 160 “Wyman Waypoints”—places mentioned in Wyman’s account of his journey—as possible.

Riders choosing the other option do not need to recreate Wyman’s exact route, only the rigor of his ride. To complete the George A. Wyman Memorial 50cc Gold ride, the biker must make it from San Francisco to New York not in 50 days, but in 50 hours.

At least, 113 years later, they no longer have to spend half the ride bumping along railway tracks.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook