How a Long-Lost Perfume Got a Second Life After 150 Years Underwater

A team of divers and archaeologists discovered the 19th-century fragrance in a shipwreck off the coast of Bermuda.

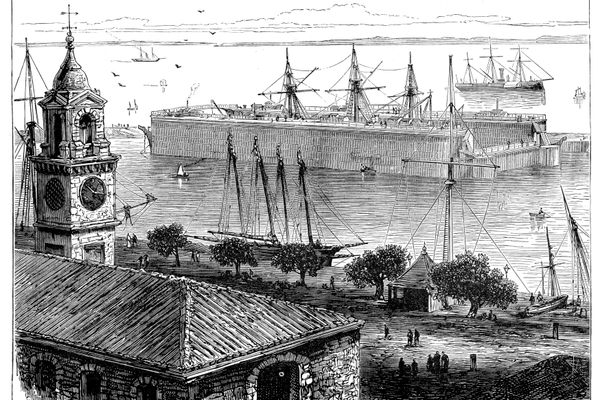

After an intense storm pummeled Bermuda in February 2011, the island’s custodian of historic wrecks Philippe Max Rouja went to do a coastal survey and spotted a partially exposed bow of a boat. The bow belonged to the Civil War blockade runner Mary Celestia, which was en route to North Carolina’s Confederate forces when it sank in 1864. The Mary Celestia is far from alone: Bermuda’s treacherous underwater reefs sank many a ship. In fact, over 300 vessels are buried around the island, each with its own history and artifacts. But this isn’t the story of the wreck itself—this is a story about a whiff of lost perfume history hiding within.

After a week of examining the wreck, a team of divers and archaeologists found a number of artifacts, including shoes, wine, and two small bottles of perfume. The items were packed together, leading the team to think they may have been gifts. Save for some mineral deposits that had formed on them, the bottles appeared to be intact. One still contained a small air bubble inside, which otherwise would have been forced out by seawater. Etched on the glass were the names “Piesse and Lubin London.”

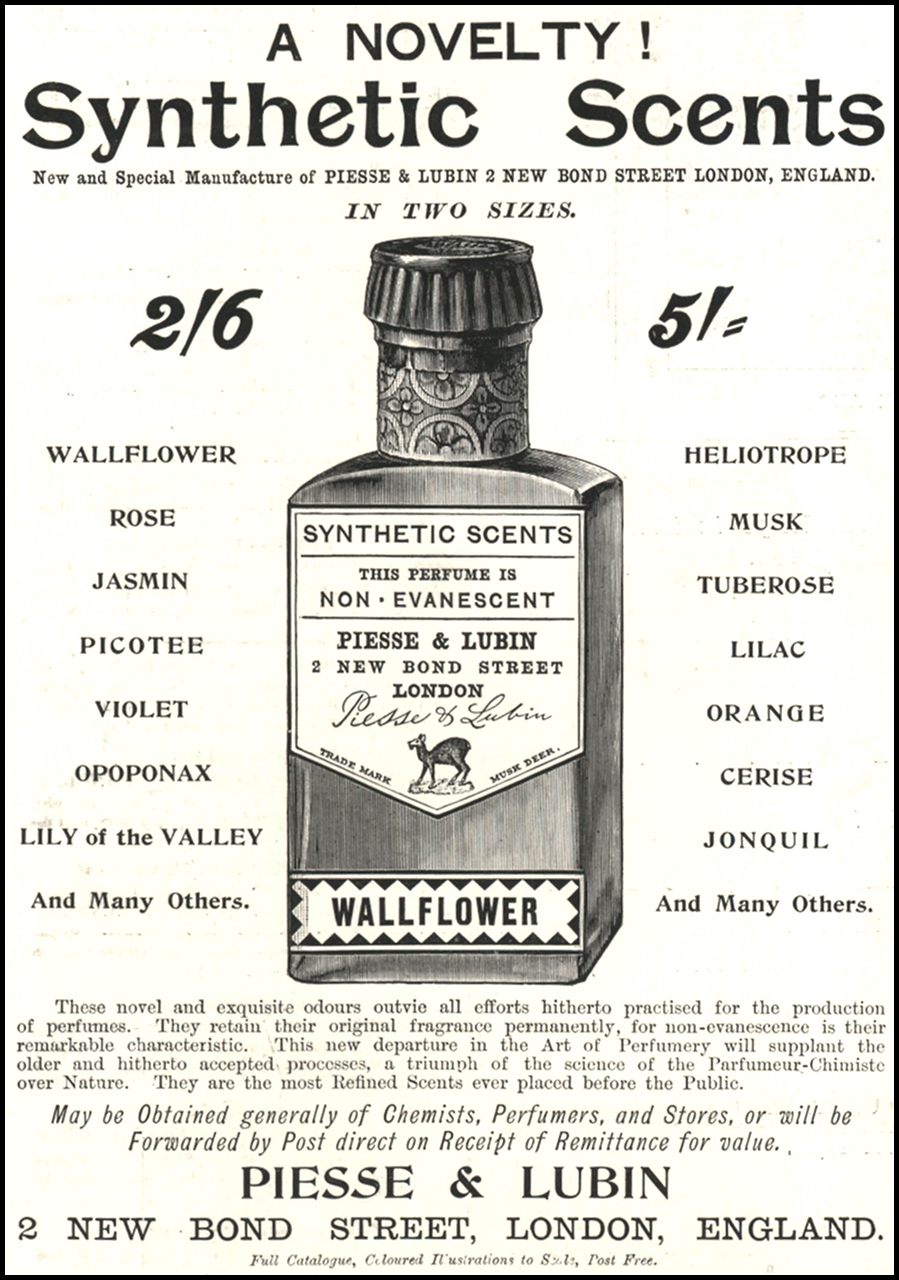

Rouja brought the bottles to Isabelle Ramsay-Brackstone, the owner of a local boutique perfume store called Lili Bermuda. Ramsay-Brackstone immediately knew they were a rare find. “In the 1800s, London was a center of the perfume industry and Piesse and Lubin was the name of a prominent perfume house on Bond Street,” she says. “It was a perfume that Queen Victoria would have worn.” Ramsay-Brackstone, who also forges her own scents, was inspired and wondered if she could recreate the fragrance 150 years later.

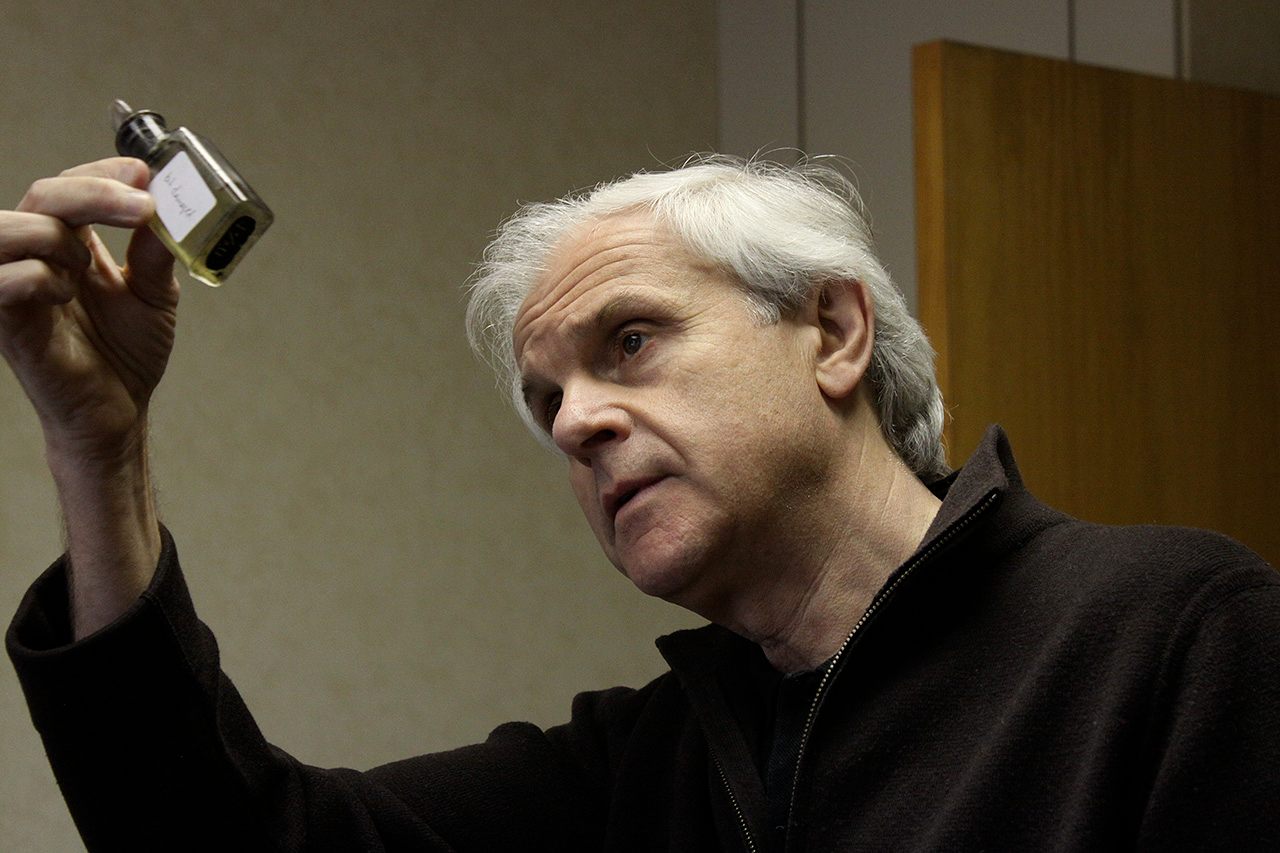

According to Bermuda’s law all artifacts recovered from the sea become property of the government, joining the collection at the Bermuda Underwater Exploration Institute. Ramsay-Brackstone obtained permission to temporarily keep the bottles as she pursued her recreation. She took her finds to New Jersey, where her friend and fellow perfumer Jean Claude Delville worked for Drom Fragrances. Drom is a large international company, which had the equipment necessary to perform gas chromatography, abbreviated GC. GC is capable of reverse-engineering a chemical formula by reading the molecular composition of a scent and spitting out the names of the associated chemical compounds. “It is somewhat similar to reading DNA,” Ramsay-Brackstone explains, except not as complex.

After carefully scraping the mineral deposits off the bottles and opening them, Ramsay-Brackstone and Delville savored the scents. One bottle gave of a whiff of a rotten smell. Unfortunately, some seawater had seeped in and spoiled the fragrance. But the other specimen survived intact after 150 years underwater. According to the duo, it smelled of orange, bergamot, and grapefruit with a faint aroma of flowers and sandalwood. There were also some musky “animal notes,” such as civet or ambergris, which were derived from animal glands in the 19th century. Unlike most modern fragrances that differentiate scents into “female” (floras or fruity notes) and “male” (woody notes), the old perfume contained both. At the time, perfumers didn’t yet make gender distinctions.

Once they had taken a whiff of the fragrance, Ramsay-Brackstone and Delville dipped a blotter stick in the liquid and placed it in the chromatograph. Not long after, the machine completed the molecular reading and generated a printout: a list of hydrocarbons, acids, and other chemicals. But while the molecular readings were easy to obtain, translating these chemicals into the associated aromatic compounds was a lot trickier.

Ramsay-Brackstone and Delville tried to search the annals of perfume for fragrances created by Piesse and Lubin co-owner Septimus Piesse. Piesse was a chemist and a perfumer who also wrote books about creating scents, but many of his records were lost. He was, however, well known for producing a very popular fragrance called Bouquet Opoponax, so the two perfumers decided the mysterious substance in the recovered bottle was likely a precursor to that product. Alas, they still didn’t find the list of ingredients he used for Bouquet Opoponax.

So Ramsay-Brackstone and Delville resorted to their own olfactory senses. After a lot sniffing and guessing, the duo settled on a few key ingredients, including orange flower, roses, sandalwood, and vanilla. “We used the chromatograph and my nose to do the reconstitution,” says Delville, adding that he and Ramsay-Blackstone tried very hard to achieve the perfume’s exact aroma. “We didn’t want to recreate just a modern version of the fragrance. We wanted to stay true to the original scent.”

Achieving this precision isn’t an easy feat, says Christina Agapakis, creative director of the synthetic biology company Ginkgo Bioworks. Agapakis previously worked on recreating the smells of extinct flowers. “Especially when you are looking at older perfumes with natural ingredients made from plants or animals, even if you do an analyses with GC, there are hundreds of molecules that can be present in very low quantities, but have a very big impact on a smell,” she says. “So it can be quite difficult to go from a GC trace to recreating a smell.”

To complicate matters further, the two perfumers had to find modern alternatives to civet and ambergris, animal-sourced ingredients that would be considered unethical today. “Ambergris comes from sperm whales,” says Ramsay-Brackstone. “It’s something they spit out like cats do with their fur balls, so it floats in the ocean until it washes out on the beach.” Therefore, it can sometimes be found naturally and without any harm caused to the animal, but even so, it can’t make a reliable and consistent ingredient. “In the old days people would gather it and use it, but in 2020 no one does it,” Ramsay-Blackstone adds.

In lieu of those controversial ingredients, the pair turned to man-made musk molecules, which today are engineered in labs safely and reliably. “I found a very specific synthetic musk called exaltone,” says Delville. “It gives the final polish and beauty to the scent.”

Beyond finding modern-day alternatives to 19th-century scents, the team also had to use different solvents. Those used by Piesse 150 years ago were skin irritants, but back then, that was of little concern since people in the 1800s didn’t wear perfume on their skin. They splashed it on their capes and scarves to protect themselves from the stench of London’s filthy streets, Ramsay-Brackstone says.

Once they settled on the ingredients, the two perfumers still had to figure out their exact proportions by trial and error. That took about 110 iterations and several months, Delville recalls. He kept mixing the ingredients in different amounts and letting them age for several weeks, after which he would send promising samples to Ramsay-Blackstone, who had since returned home.

Finally, when they got close to what they presumed was the original formula, Delville flew to Bermuda. The local scents naturally present in the air—sea, salt, and sand—and even the altitude can affect how a smell is perceived, he explains. “You have to do the final touches at the location where you will launch your fragrance,” he says. “We both agreed on what needed to be done—we had to increase the level of orange flower and sandalwood.”

The two perfumers named their creation Mary Celestia. Naming the perfume after a ship that restocked Confederate forces wasn’t meant to commemorate the blockade runner or any historical figures, Ramsay-Brackstone says. She believes that the bottle was originally intended as a gift, and she wanted to honor that long-gone relationship. “Perfume, even 150 years ago, was meant to be an intimate gift between two people who had profound feelings for each other,” she adds.

Ramsay-Brackstone issued a limited edition of the restored scent in September 2014—a century and a half after the ship’s demise. That run included 1,854 bottles, a reference to the year the ship sank. She donated some of the proceeds to the Professional Association of Diving Instructors, also known as PADI, an organization that teaches young Bermudians how to dive, an important skill at on the island. “This perfume waited for 150 years to be worn,” Ramsay-Brackstone says. “We were really excited to bring it to the people.”

Recreating the perfume was quite the olfactory accomplishment, Agapakis says. Oftentimes, when scents are recreated based off the gas chromatograph analyses, they come out flat, missing a certain element of complexity.

But that’s not what happened with this particular revival. The fragrance was multifaceted, and consumers responded enthusiastically to its electric array of aromatic components. The limited edition quickly ran out and customers wanted more. Today, Mary Celestia is sold at Lili Bermuda and online for $130. It also comes in a travel size at $35.

As the perfume aged it became richer, akin to a good wine. “The older it gets, the more of its personality comes out,” says Delville, who since started his own company, The Society of Scent. “What Piesse did a century and a half ago was magic, which we are enjoying today.”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook