Smokey the Bear Has Nothing on These Forgotten Forest Mascots

Meet The Guberif, Johnny Horizon, Howdy The Good Outdoor Manners Raccoon, and more!

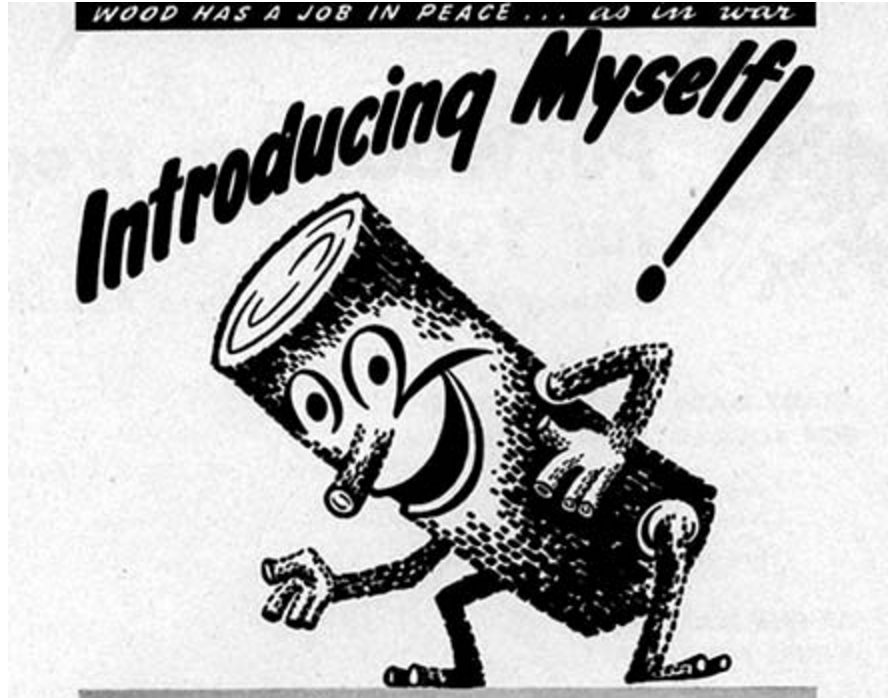

You know Smokey the Bear—but have you met Woody the Smiling, Animated Log? (Image: Forest History Society)

Earlier this month, as wildfires blazed up and down the West Coast of the United States, Smokey the Bear turned 71 years old. This past summer has been terrible for fires, as record dry weather and average human incompetence have combined to turn forests from California to the Canary Islands into tinderboxes. You can almost picture Smokey checking the news, staring at his candleless cake, and sighing a bear-sized sigh.

But Smokey wasn’t always alone in his publicly fire-hating ways. Since the 1940s, American organizations have marshaled a whole menagerie of spokesflora and fauna to guilt, tempt and cajole us into giving a darn about the environment. (The Forest History Society’s blog, Peeling Back the Bark, has a running series profiling many of them.) Although all were eventually defeated by Smokey and his sidekick, Woodsy Owl, they still have things to teach us. Below are six of the country’s lost forest protectors, from Woody the Log to Johnny Horizon to Howdy the Good Outdoor Manners Raccoon.

1. Woody the Log

Woody, apoplectic at his human friend’s ignorance. (All images: Forest History Society)

In the early 1940s, American Forest Products Industries, a trade group representing the country’s lumber interests, found themselves in the thick of a PR crisis. Forest fires were on the rise, public opinion was sinking, and government regulation threatened. The AFPI figured if they could get their side of the story out there, the American people would be on their team again. “They wanted to educate locals about trying not to start forest fires, because trees were, in essence, standing capital,” explains Jamie Lewis, a historian at the Forest History Society. “But they also wanted to help them to understand logging and the benefits of good forest management.”

In 1944, the group debuted a versatile solution: a cartoon mascot named Woody, described in his introductory press release as “a smiling, animated log.” Essentially a chunk of wood with arms, legs, a twig nose, and a big grin, Woody was tasked with getting across these various forest-related messages.

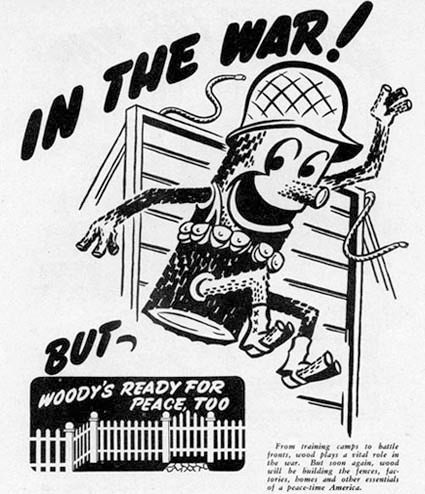

In one early ad, he strikes a jaunty pose as an accompanying text box explains how a forest is “a farm that can produce forever.” In another, he leaps a high, wooden wall while decked out in an army helmet and an ammo belt, to remind citizens of the role wood plays in wartime pursuits. (“But—Woody’s ready for peace, too,” assures an inlay, showing a demure white picket fence, presumably made of softer Woodys.)

Woody was perfect for the job—a round peg in a round hole, if you will—and by the 1950s, he was everywhere, predicting forest fire danger on road signs, shilling for redwoods on dinner placemats, and holding hands with Santa on Christmas cards. Costumed Woodys (some inexplicably frowning) showed up at festivals and department stores. Kids could even read about the exploits of their favorite log in special miniature comic books, in which he stops their less well-educated peers from burning down the forests, like chumps.

But all wood things must come to an end, and Woody was eventually chopped out of the public consciousness, overshadowed by newer, fresher mascots—like those we’ll meet below.

2. The Guberif

Hint: try spelling it backwards. (Images: Forest History Society)

There were few activities dearer to your average midcentury American’s heart than driving, smoking, and taking in some choice scenery. But in the 1930s and ’40s, a steady increase in forest fires forced officials to confront the dangers of indulging in all of these activities at once. “The constant fear was, as people drove through the woods, they would flick their cigarette butts out the window,” says Lewis.

Enter the Guberif—a strange-looking bug that, starting in 1950, swarmed the public life of Idaho. The inspired creation of the state’s Keep Green campaign, the Guberif was a dopey menace, with drooping antennae, half-closed eyes, and an unending arsenal of smoking equipment. Nobody wanted to be a Guberif—and they were reminded of this fact frequently, as they pulled anti-Guberif postcards out of their mailboxes, ran into human-sized Guberifs at educational events, and drove over “DON’T BE A GUBERIF—PREVENT FOREST FIRES” painted on the tarmac outside highway rest stops.

Open season on Guberifs proved all too successful, and the bug eventually sank into obscurity, although Lewis says there’s still at least one highway pulloff that bears his insignia. But he was successful enough in his own time that Idaho Firewise, a new fire prevention group, may bring him back. Next time you’re in Idaho, watch out for a dopey bug, probably vaping this time.

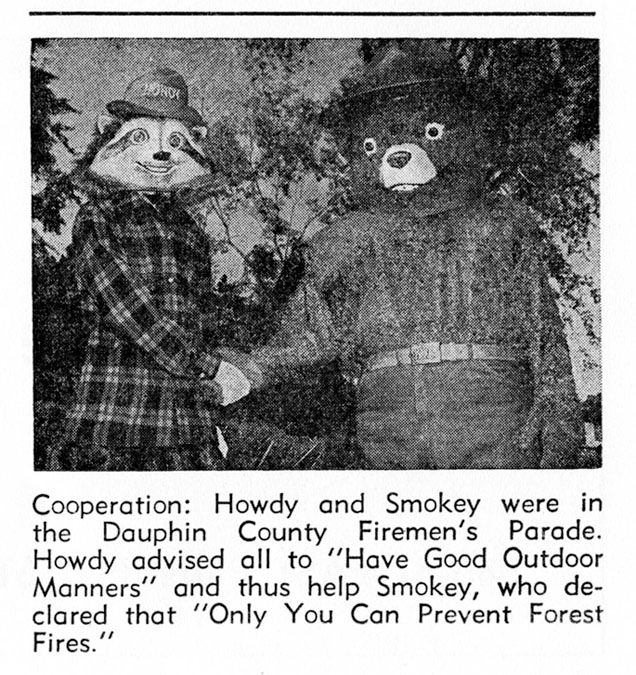

3. Howdy the Good Outdoor Manners Raccoon

Howdy, dedicated to his title. (Images: Forest History Society)

After the Guberif, when agencies sought to shame people out of burning down the forest, they generally refrained from inventing new species. Instead, they began turning to tried-and-true critters—like Howdy, the Good Outdoor Manners Raccoon. A small creature with a large name, a cute hat, and a flannel shirt, Howdy was introduced in 1959 by the Pennsylvania Forestry Association, and went on to have a brief but illustrious career in litter prevention and outdoor etiquette.

“The idea with most of these mascots was, if you get the kids indoctrinated, they’ll convince their parents,” says Lewis. In this spirit, Howdy was named by first grader John Hoyes, who won a contest that drew thousands of entries. For his first public foray, Howdy was plastered on 100,000 book covers, designed so that when children wrote their names on their books, they also signed his “Good Outdoor Manners Pledge,” promising to feed birds, protect flowers, and stop fishing in their neighbors’ streams without permission.

Some Howdy/Smokey cross-promotion, at the 1964 Dauphin County Firemen’s Parade.

Howdy and his values proved popular enough that both were adopted by a dedicated Seattleite, Margaret Robarge, who started a Good Outdoor Manners Association over on the West Coast. Through GOMA, Howdy soon had a new batch of fans, along with his own monthly magazine (he was also billed first in a 30-minute film, Recreation or Wreckreation?). But Howdy, too, lost the limelight, perhaps because of Woodsy Owl—whose slogan, “Give A Hoot, Don’t Pollute” was somewhat more memorable than Howdy’s unwieldy surname.

4. Johnny Horizon

Johnny Horizon shows off his signature stride. (Images: Forest History Society)

If any mascot came close to taking over for Smokey, it was Johnny Horizon—a clean-cut, square-jawed ranger whose love of country showed through his kind eyes and his strong hands, which seemed to constantly point downwards at the land. Introduced in 1968 by the Bureau of Land Management, Johnny won hearts and minds from coast to coast. “He’s not as well known as Smokey the Bear, but if the Department of the Interior can help it, Johnny Horizon soon will be,” wrote Michigan’s Argus-Press in 1975. “At least he’s sexier looking.”

For over a decade, this appeal brought Johnny far. His highest times came during the runup to the 1976 bicentennial, when he spurred the campaign to “Clean Up America For Our 200th Birthday.” He made cameos on Fat Albert. Kids signed Johnny Horizon pledge cards, and went hunting for pollution with their Parker Brothers Johnny Horizon Environmental Test Kits. Singer Burl Ives put his considerable voice behind Johnny. “He showed up on the Johnny Cash show to sing the Johnny Horizon song!” says Lewis. “Nobody’s sung the accolades of Woodsy Owl on a national program.”

A Johnny Horizon pledge card.

But even this was not enough to dethrone the bear and place Johnny at the helm of America’s environmental conscience. In 1976, the campaign’s heads asked to double Johnny’s budget; in response, the Department of the Interior cut his funding entirely, and he went striding off over the horizon that was his namesake. Farewell, Johnny—we hardly knew you.

5. Sam Sprucetree

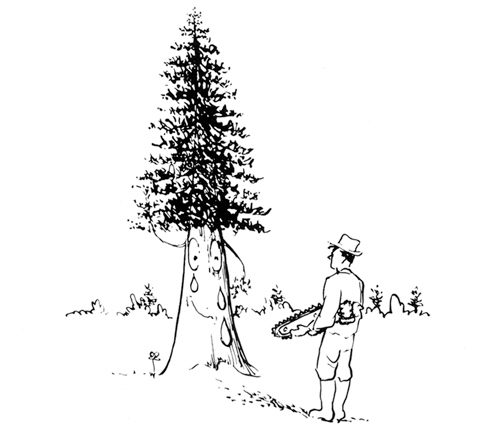

Sam Sprucetree weeps with joy at his impending doom. (Images: Forest History Society)

The Giving Tree, the 1964 Shel Silverstein classic, tells the tale of a tree who so loves a little boy, she gives up everything for him—her apples, her branches, and eventually her whole trunk.

Sam Sprucetree: My Autobiography Sort Of, from around 1978, seems to be going for the same kind of thing, but through a slightly different lens. “The current-day analog that I like to point out is, here in the South you’ll pass barbecue restaurant signs on which you’ll see a pig pouring barbecue sauce on himself and smiling,” says Lewis.

A much cultier classic, Sam Sprucetree’s tale was written by Consolidated Papers, Inc., a Wisconsin paper company that hoped to convince savvy ’70s readers that its cutting practices were good for the environment. “Over the years, our mills have used many of Sam’s brothers, sisters, cousins, and kinfolk of all classes,” the introduction begins.

Sam faces down a fire.

Sam himself goes on to describe his situation—“I’m about to be sliced into pulpwood,” he explains—and to relay the travails and triumphs of his woody life, including facing down a forest fire, which looks like a four-footed octopus. By the end, he has sung the praises of the era’s new, responsible logging practices, and has left us with an all-American lesson: “As I go rolling down the line I’m going to be thankful that I’m leaving a better chance in life for my seedlings and grand-seedlings than I had when I was young.”

A character who martyrs himself for the cause is, by definition, not long-lasting, and Sam appeared only in this one publication.

6. Spunky Squirrel

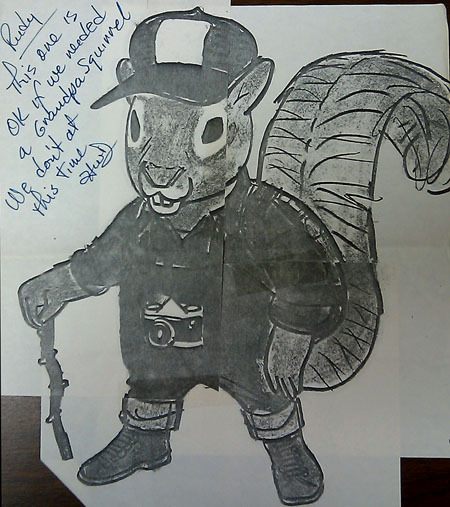

The coolest non-cat in town. (Image: Youtube)

In the mid-1980s, the definition of “forestry” was changing once again, expanding past the forests proper and into towns and cities. To reflect this, the nonprofit American Forestry Organization developed an Urban Forestry Program, focused on teaching people how to care for trees closer to home. For this new initiative, they needed a mascot who could draw in America’s youth—not through goofiness or fearmongering or paternalism, but through pure, unadulterated cool. They needed, in the words of AFA leader Hank DeBruin, “a young dynamic City Squirrel”—a Spunky Squirrel, if you will.

“I love Spunky because he’s ahead of the curve,” says Lewis. “He’s got the baggy pants, the high-top shoes, and the hat he sometimes wears backwards.” An early draft of Spunky, in which he’s a bit more square, was returned to artist Rudy Wendelin with the note “This one is OK if we needed a Grandpa Squirrel.”

Nice try, Gramps. (Image: Forest History Service)

The strategy worked, and soon kids all around were wearing Spunky Squirrel buttons, flinging Spunky Squirrel frisbees, and watching the rodent himself appear on Romper Room. A 1984 PSA shows Spunky somersaulting out of a tree and sharing some tree-protection tips after being spotted by Danny, who yells “It’s a squirrel! It’s Spunky Squirrel!”

Even that kind of name recognition couldn’t save Spunky from his fate—within a few years, he was smothered, like all the others, by the all-consuming power of Smokey. Fire prevention is no place for biodiversity.

Naturecultures is a weekly column that explores the changing relationships between humanity and wilder things. Have something you want covered (or uncovered)? Send tips to cara@atlasobscura.com.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook