Stolen Artifacts! Drunk Teens! And More True Tales of Florida’s First State Archaeologist

Vernon Lamme was not your average archaeologist.

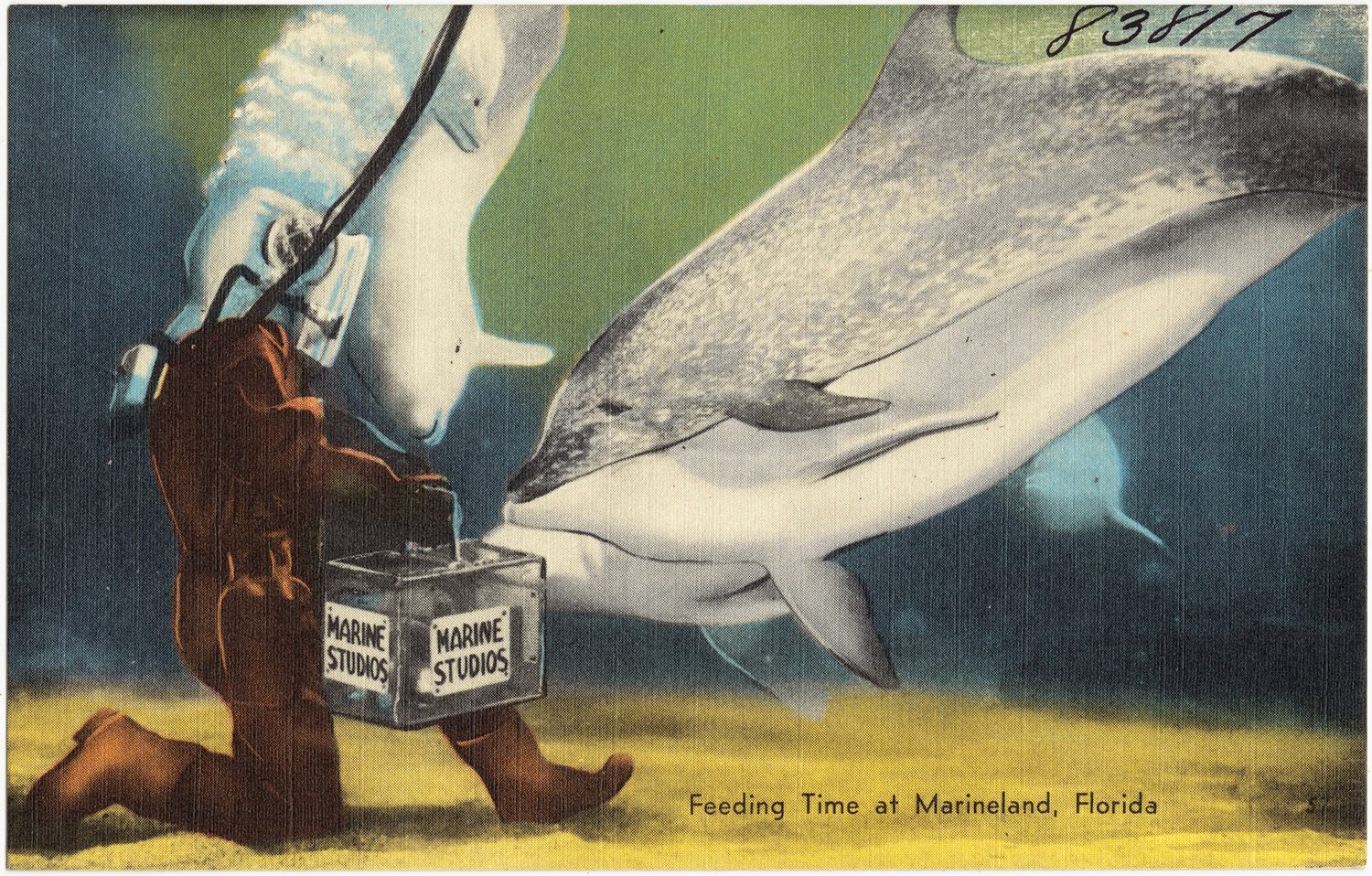

Vernon Lamme didn’t quite seem the type to be an archaeologist. With his prominent chin and substantial waist, he was neither a swashbuckling, world-traveling Indiana Jones nor a meticulous, dust-covered scholar. He sometimes like to play the part of the adventurer—in pictures from the 1940s, when he was excavating burial sites at the aquatic theme park Marineland, he’s wearing a pith helmet—but his territory was Florida.

He stuck to it, and it paid off: in 1935, the governor appointed him State Archaeologist, the first in Florida and one of the first anywhere in the country.

But if the position paid off, it was because Lamme made sure of it.

“He was known among archaeologists as being a shady, charlatan type character. He was a real showman. I look upon him like a P.T. Barnum,” says Jeffrey M. Mitchem, an archaeologist who’s researched and written about Lamme’s life and career. “But maybe not as smart as that.”

Today, most states have an official State Archaeologist, or someone serving in a similar role. The position began as more of an honorary role, but after Congress passed the Historical Preservation Act in 1964, new state historic preservation offices started hiring archaeologists to review development projects and help protect valuable archaeological sites.

“Just like we protect the birds and bees with environmental laws, we protect cultural resources,” says Nicholas Bellatoni, Emeritus State Archaeologist in Connecticut and past president of the National Association of State Archaeologists. If state archaeologists identify archaeological sites that are potentially significant, they might recommend a development be paused while a survey is conducted. This doesn’t always go over well. “Any state archaeologist is used to controversy,” says Bellatoni.

But not the type of controversy that Lamme incited. In his first stint as state archaeologist, he lasted just six months—and his scandals included getting hordes of teenagers drunk.

Lamme was born in Kansas, in 1892, and when he was 20, his family moved to Florida, to stake a homesteading claim on Merritt Island, a long strip of land off the state’s eastern coast, next to what’s now Cape Canaveral. It was a rough set up: most of the houses were simple shacks, with hand pumps in the back, and there were no roads, schools, tools, or unemployment checks, he wrote later. There was, occasionally, “excellent wine made from grapefruit juice.”

In his 20s, Lamme started working in newspapers, first as a local correspondent, and then moving to Naples to start the Transcript. In 1931, the senator from Key West promised to find him a job, and he began working for the state government as a “verifier in the Enrolling Room,” where he made sure bills passed by the state senate were in the right form when they went to the governor for a signature. But he also continued submitting stories to newspapers in Key West and Fort Myers.

By 1935, he had become legislative secretary to the same senator who had originally lured him to the capital. It was from this position that he launched himself as state archaeologist. He wrote the bill that created the position and, after it passed, convinced the governor to appoint him to the office, though he had no training and little experience as an archaeologist.

In the southeastern states at the time, though, that wouldn’t have been so unusual. There was little professional archaeological work being done in Florida, and enthusiastic amateurs could finagle their way into digs or make their own contributions. In the mid-1930s, though, the state was about to experience a small boom in archaeological work, funded by the federal government.

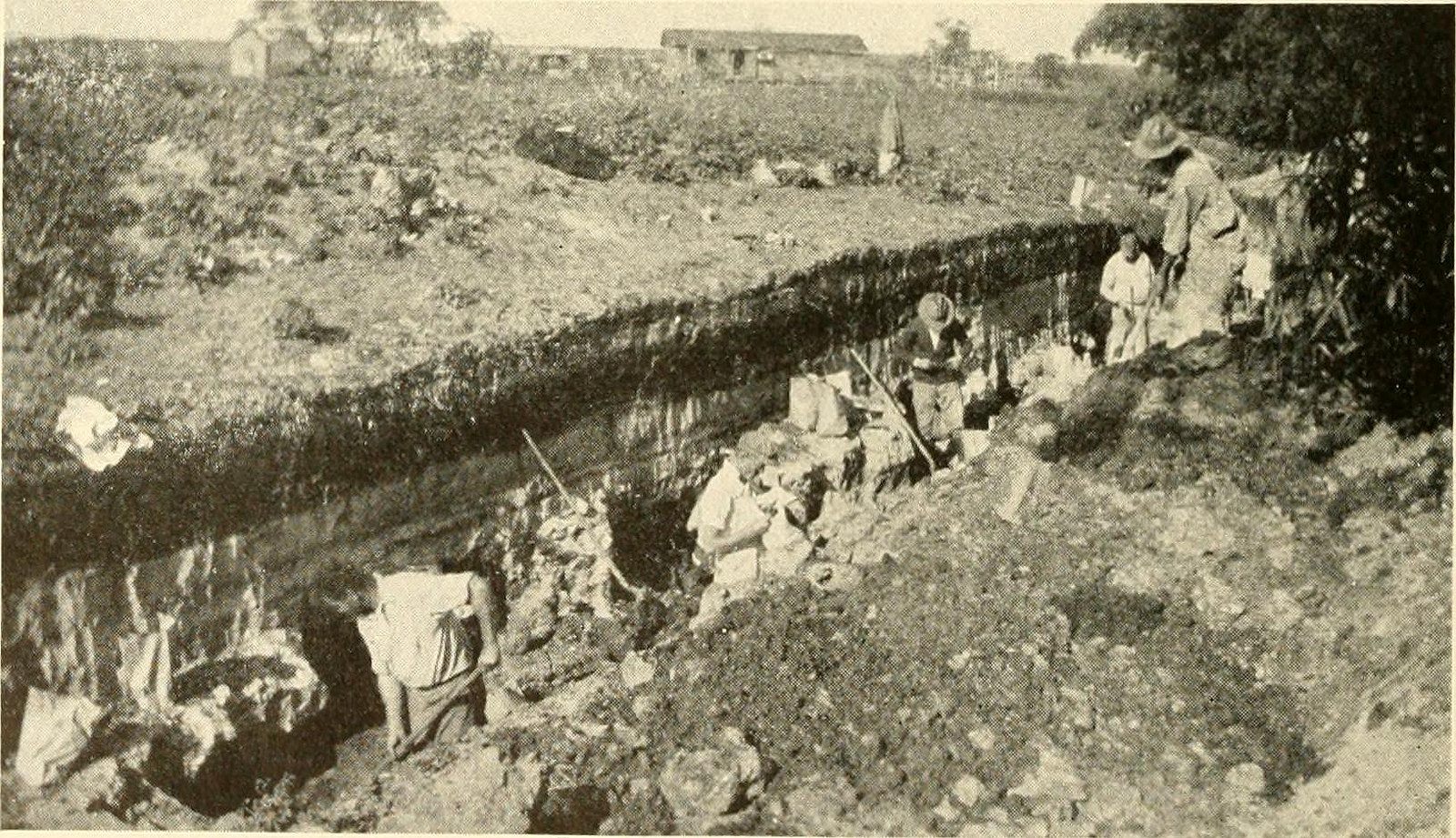

As part of the New Deal, the Civil Works Administration was launching large archaeology projects, under the supervision of the Smithsonian, in “states with mild climates and large numbers of unemployed workers,” as Edwin Lyon puts it in A New Deal for Southeastern Archaeology. Whatever artifacts were found would be split between the state and federal governments. As the newly appointed State Archaeologist, Lamme would be in charge of the state’s side.

“Because he was called the state archaeologist, he was supposedly involved in all these projects,” says Mitchem. “Some of the other people involved in these projects, who were competent, trained people couldn’t stand him.”

The problems began quickly, as Mitchem discovered while researching Lamme’s life. The digs that Lamme was overseeing kept shoddy records, so that archaeologists looking at the reports he wrote can find little to elucidate what was actually found. At the site of one educational project, Lamme “bought moon-shine whiskey and lemons and succeeded in getting the crowd drunk,” reported one of his enemies, J. Clarence Simpson, an employee of the Florida Geological Survey and an actual archaeologist.

Some of Lamme’s young employees had “never drank whiskey before in their lives,” Simpson wrote. “I feel sure that every resident of the town will recall very clearly the shameful incidents which followed.” Lamme also took the government trucks provided for the work and rented them out for $8 a day, a fee which he presumably pocketed. More seriously, some of the best artifacts from the dig disappeared.

“Lamme was good friends with a major collector in Miami,” says Mitchem. “Apparently he was letting this guy take some of the cream of the crop stuff that they were finding.”

After six months, these transgressions lost Lamme his new position. He was suspended as State Archaeologist.

Surprisingly, this was not the end of Lamme’s archaeological career. He convinced a new governor to reinstate him as state archaeologist in 1937, only to resign a few months later to begin a different government job, as a citrus fruit inspector. In 1939, he started working with Marine Studios, a SeaWorld-like park that focused on dolphins.

At the Marineland site, he started excavating mounds built by Native Americans and in 1940, in connection with this work, he got himself reappointed as State Archaeologist yet again. That same year, he was also elected Alderman for Marineland, Florida, where the park was located.

At Marineland, Lamme’s love of a good story, his interest in archaeology, and his need to make a buck finally came together. “Ever the showman, he convinced the owners of Marine Studios to make him and the excavations part of the attraction itself,” writes Mitchem. “This indeed proved popular.” Visitors to Marineland could pay 25 extra cents to view the mounds, the excavated burial sites, and eventually the Seminole family Lamme convinced to live on site. He himself gave lectures.

After America entered World War II, though, Lamme found a better government job, as, ironically, a fraud investigator, and after the war, he went back to writing. He never stopped thinking about archaeology, though: In his book, Florida Lore Not Found in the History Books!, written later in his life, he’s still trying to advance a pet theory, that Florida was once occupied by the Maya people.

“As State Archaeologist of Florida, I had the opportunity to tramp over every deer trail and cowpath in the every county of the state – and the more Indian mounds I studied the more firm was my belief that the Mayas once roamed these trails,” he wrote.

Evidence? There’s little. But that never concerned Lamme: he made the world what he wanted it to be.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook