The 1913 ‘Nature Man’ Whose Survivalist Stunts Were Not What They Seemed

Joseph Knowles had wilderness skills, but didn’t necessarily want to use them.

Joseph Knowles prepares to enter the wilderness. (Photo: Public Domain)

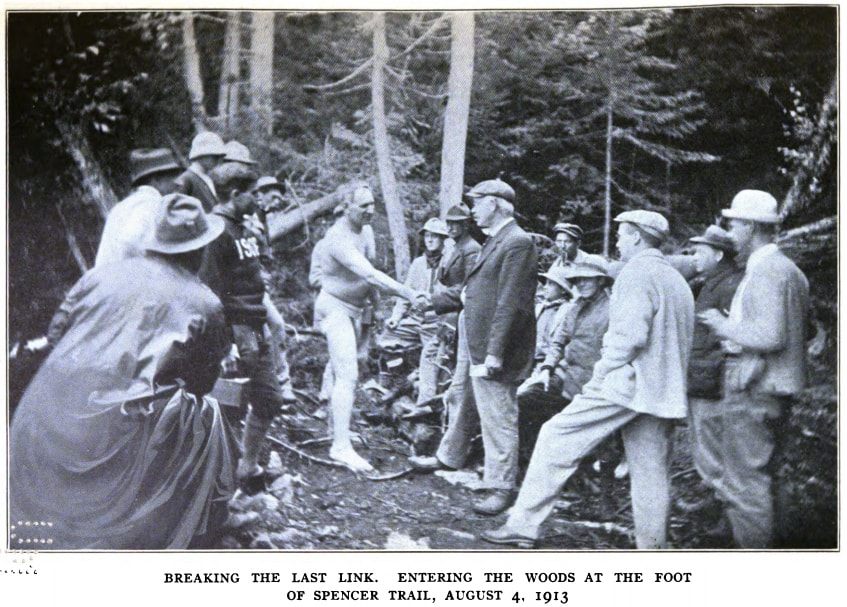

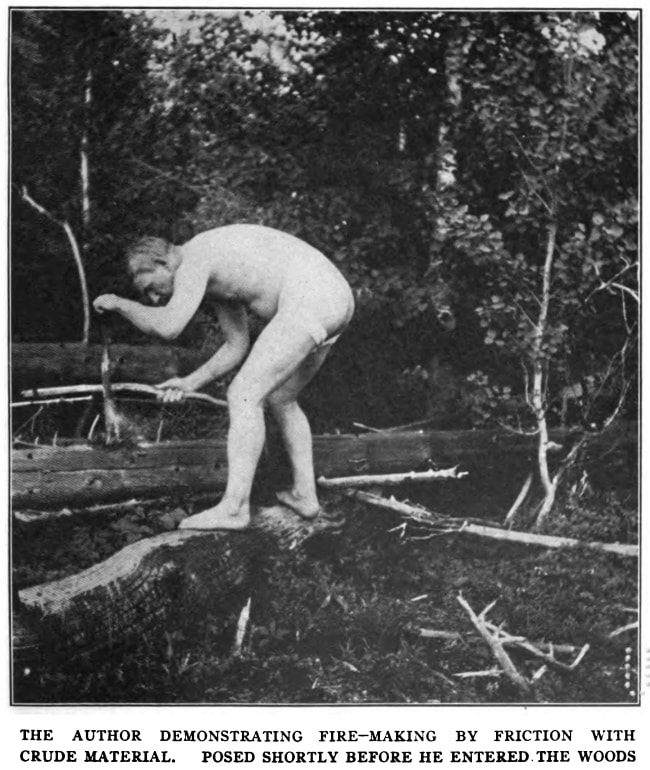

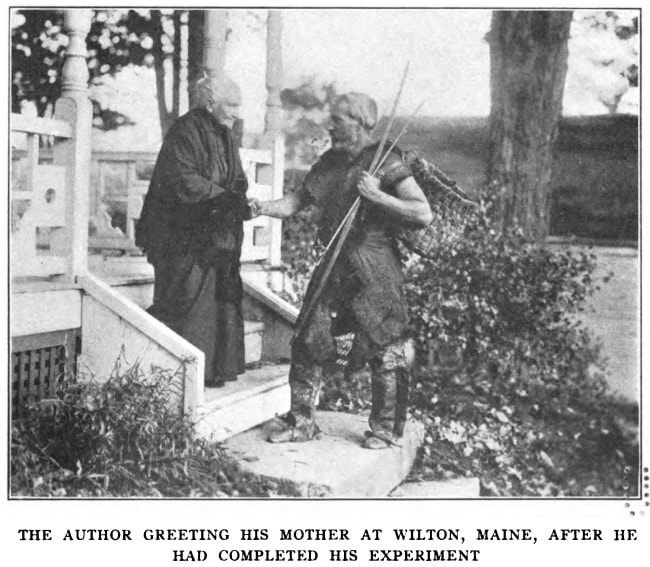

One gray day in the summer of 1913, a man named Joseph Knowles stood on a muddy logging road in northern Maine and stripped off his clothes until he wore only a white jockstrap. In the preceding weeks, the media had been alerted that he planned to walk into Maine’s Dead River Wilderness and survive for 60 days, using only his naked body and his wits.

A giddy throng of friends and reporters attended to see him off. Photographers from the Boston Post clicked away as he disrobed, revealing a pale, pudgy torso. As a professional cartoonist living in Boston, Knowles hardly looked fit for the role of America’s preeminent wild man. But his eclectic life experiences—a childhood spent in rural Maine, an adolescence roaming the world on naval ships, and a young adulthood working as a hunting guide—had equipped him with a surprising array of skills.

He assured the reporters he would emerge from the woods with a full deerskin outfit, perhaps an entire wardrobe. The reporters asked what he would eat. His answer: wild cherries, artichokes, and frog legs—at least until he could snag himself a deer.

Two doctors performed an exam to verify that he was not secretly smuggling out any survival tools. He carried nothing; even the jockstrap would be shed once he was out of camera-shot. Knowles was offered one final cigarette, like a man standing before a firing squad. He took a few puffs, stubbed it out, called out “See you later, boys!” and dissolved into the forest.

(Photo: Public Domain)

The reporters returned to Boston, where over the next eight weeks they faithfully recorded the saga of the “Nature Man.” Scribbling on a piece of birch bark with a piece of charcoal and depositing the messages in an agreed-upon location, Knowles relayed news of each new trial and triumph: of surviving his first two nights out in the cold; of felling partridges and deer and with a handmade bow and arrow; of catching trout with his bare hands; of building a lean-to; of weaving a pair of sandals out of cedar bark; of painting a picture using only natural dyes; and, most sensationally, of trapping, clubbing, and skinning a black bear.

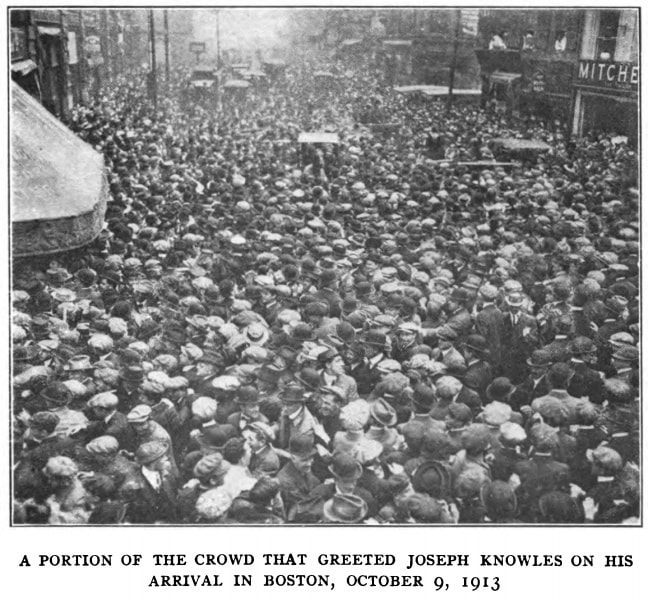

In Boston, the newspaper stories were a smash. The Post’s moribund circulation soon doubled. Knowles’ stunt ended with a thrilling chase, as game wardens—miffed that Knowles had been hunting out of season—reportedly chased him to the border of Canada. He emerged, looking bedraggled and 30 pounds lighter, near the town of Megantic, Quebec. From there, he caught a train south, wearing his stinking bearskin and waving to crowds of onlookers at each stop. Back in Boston, a throng of 200,000 people—nearly a third of the city’s population—poured out onto the streets to welcome him home.

(Photo: Public Domain)

Those crowds’ fascination with the Nature Man ran deeper than mere novelty. Without entirely intending to, middle-aged, middle-class Knowles had suddenly become a key figure in a national conversation about the pitfalls of modernity.

Around the turn of the century, there arose a widespread fear that white men, raised in cities, were becoming weak, over-intellectual, and morally dissolute. At the same time, many Americans—influenced by European romanticism and the dawning realization that the wilderness is not infinite—ceased regarding the wild as a grim and dangerous place, and instead viewed it as sublime.

Middle and upper class urbanites, crammed into evermore crowded and polluted cities, began studying woodcraft and exoticizing more so-called natural and “primitive” ways of life. Native Americans, once considered blood-thirsty heathens, were increasingly seen as noble, fierce, and enlightened stewards of the earth, whose wisdom needed to be preserved and whose flinty independence needed to be emulated.

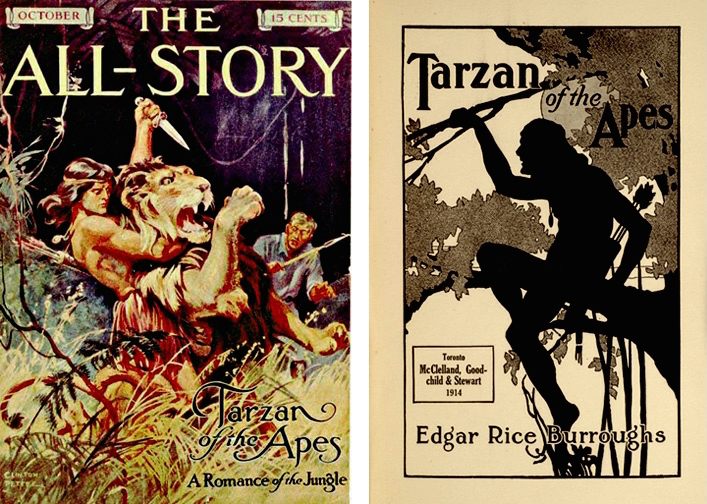

This sea change in popular opinion regarding wild land and “savage” people played a part in the swift rise of the Scouting movement and hundreds of summer camps, which promised to toughen boys up with fresh air, vigorous exercise, and “hearty, manly fun.” The hunger for such stories was fed by a series of wildly popular adventure books, like Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan series and Jack London’s The Call of the Wild.

Tarzan stories from 1912 and 1914. (Photo: Public Domain)

As Theodore Roosevelt—a formerly bedridden Manhattan rich kid turned avid outdoorsman, honorary Scout chief, and soon-to-be president—wrote to a friend in 1899, “Over-sentimentality, over-softness, in fact washiness and mushiness are the great dangers of this age and of this people. Unless we keep the barbarian virtues, gaining the civilized ones will be of little avail.”

In this grand narrative, Knowles was cast in the role of single-combat warrior in the battle against the creeping “sissification” of urban white men. If he failed, it meant American boys were doomed to effeminacy, lassitude, and alienation from nature. But if he succeeded, it would prove that the white man had some fight left in him yet.

Knowles seemed to be fully conscious of his symbolic role in this mythic drama. From the forest, he wrote a letter (presumably, on birch bark) to then-President Woodrow Wilson, declaring: “My object is to demonstrate that modern man is not only the equal of primitive man in ability to maintain himself, but that civilization has so improved the human mind that he may add to primitive life accomplishments which our early ancestors never knew.”

(Incidentally, a nearly identical line is pronounced by Tarzan’s father, Lord Greystroke, shortly before he is mauled to death by an ape.)

Given this cultural context, it makes sense that when Joseph Knowles walked out of the Maine woods clad in a bearskin robe after 60 days in the wilderness, he was received not just as a survivor, but as a conquering hero.

However, something was amiss. He had returned home suspiciously muscular, it was said, and with too few bug bites. Even his famed bearskin coat reportedly showed no signs of clubbing, but instead, on closer inspection, bore four neat bullet holes in its side.

(Photo: Public Domain)

Less than two months after his heroic return to Boston, the Post’s rival paper, the Boston American, ran a scathing exposé charging that Knowles had spent most of those two months sleeping in a comfortable log cabin, dodging reporters, drinking beer, eating canned food, doing calisthenics, and working on his tan. (These charges were mostly confirmed by a lengthy feature that ran in the New Yorker in 1938, and by Jim Motavelli’s authoritative 2008 history, Naked in the Woods: Joseph Knowles and the Legacy of Frontier Fakery.)

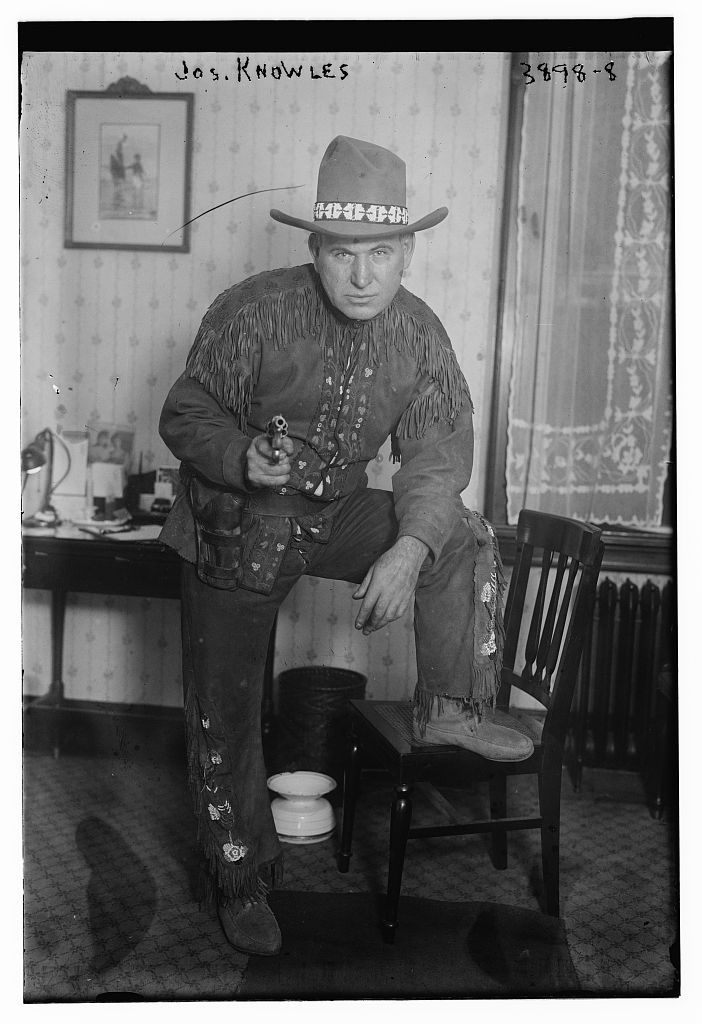

Even as he was dogged by rumors of the hoax, Knowles continued to book speaking engagements under his popular moniker, “The Nature Man.” He was featured in vaudeville shows and a Hollywood motion picture, Alone in the Wilderness—the same name as the best-selling book he published that year. At the time, he was making as much as $1,200 (roughly $29,000 in today’s dollars) each week from his speaking fees.

Two years later, Knowles attempted a repeat of his famous stunt out on the West Coast. This time, apparently, he honestly managed to live off the land for 30 days without any outside assistance. Unfortunately for him, the onset of the First World War caused the coverage of his exploits to be buried in the back of the newspaper. (“Many a Californian doesn’t know to this day whether Joe Knowles ever got out of the woods,” joked the American Mercury in 1936.) Knowles spent his final decades living in a seaside shanty in Washington, where he sold his paintings and gathered wild food from the sea.

Knowles strikes a pose sometime between 1915 and 1920. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ggbain-22094)

Since Knowles never confessed to faking his first wilderness sojourn, the central mystery of this saga remains unanswered: if Knowles had the ability to live off the land, why didn’t he just do it on his first try, when the whole nation was watching? The answer, according to Motavelli, is simple: “He was very capable, but also lazy!”

In the end, it appears that the reality of what Knowles did in the North Woods for two months is far less interesting to us than the symbolism of the act. Even as late as 2007, magazines were publishing glowing accounts of Knowles’ Maine adventure that revel in the romance of his primal independence, while wholly omitting any allegations of fraud.

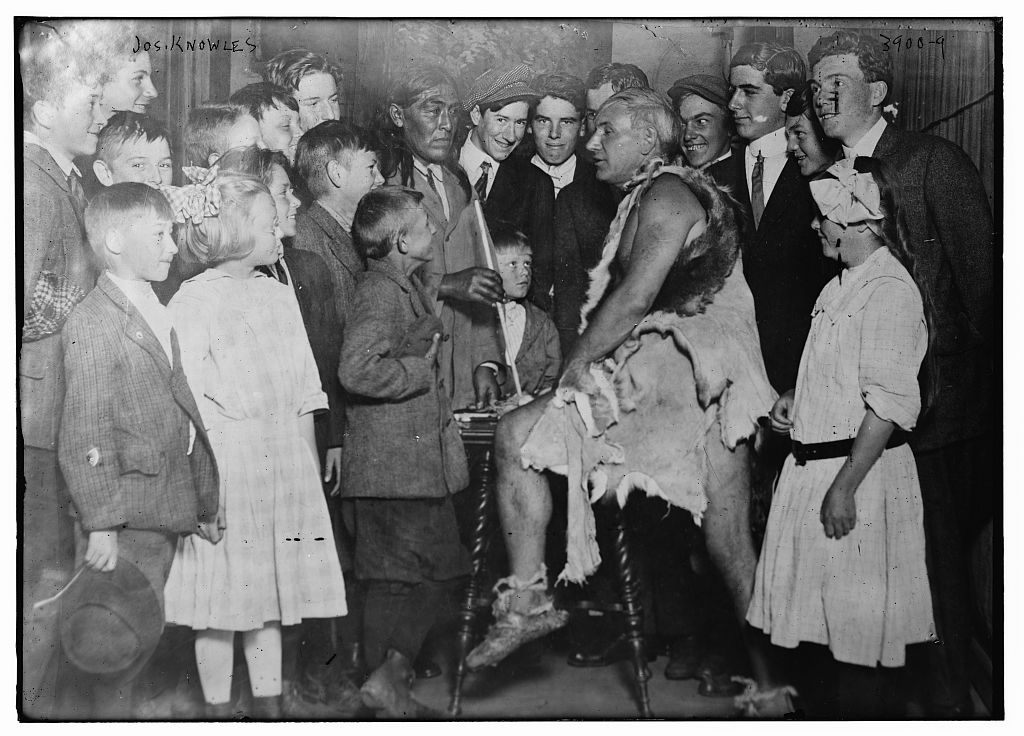

Back in 1913, upon his return from the wilderness, a grand spectacle was made of Knowles reacclimation to civilization. Following a speaking engagement at a women’s college (the Sargent School of Physical Training), where the students were invited to stroke the “perfect” skin on his back, Knowles was transported to Filene’s department store, where he was manicured, barbered, and clothed in a fine suit.

Knowles tells tales to an enthralled crowd. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ggbain-22113)

Much like his time in the wilderness, this event was orchestrated to maximize publicity; Filene’s advertised the event in the Post, inviting the public to come witness his transformation. “He will come in his woodland attire,” the ad copy proclaimed, “composed largely of skins and bark, and will go through the process of evolution from the primitive to the modern man.”

But even decades afterward, when his hair had gone snow-white and his torso had reverted to flab, people still clamored to see him in his primitive costume. And so, once more, he would dutifully don his bearskin cloak and strike a dashing pose.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook