The Best Political Cartoon In History Is This Fake Banknote from the Panic of 1837

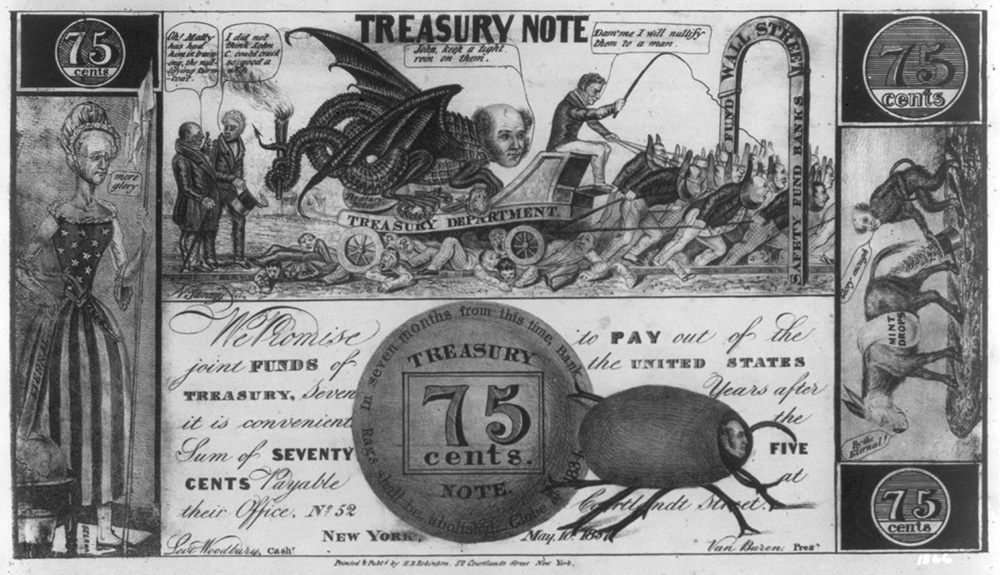

This $.75 bill features a human-faced dung beetle, a donkey pooping money, and Andrew Jackson in flag drag.

Blur your eyes, and the banknote above looks normal enough. It has the right proportions. It’s covered in intricate line drawings, so as to discourage counterfeiting. It’s got serious-looking slogans and strongly penned numbers. If someone passed it to you across a counter after a long night, you might not look twice.

Focus, though, and you’ll notice a few weird things going on. A panel on the left side shows a bony, balding person dressed in a tattered American Flag. Across the top, a dragon rides a carriage through the streets, crushing pedestrians willy-nilly. The right side sports a donkey defecating into a monkey’s top hat. And along the bottom, a dung beetle with a human face rolls a poop ball emblazoned with the bill’s weird denomination: 75 cents.

In case you hadn’t guessed, this bill is not legal tender. It’s a parody note, “issued” during the Panic of 1837 to lampoon the figures on whom the artists blamed the crisis. Today, it provides a monstrous sort of history lesson, along with a timeless example of bonkers political art.

Like most economic crises, the Panic of 1837 was made of many stressful strands. Mostly, though, it hinged on how different parties defined money. In the early 1830s, Andrew Jackson was generally running a “hard-money” White House, insisting that it was best to pin the U.S. economic system on money that was more closely tied to actual value—in this case, gold and silver coins, known as “specie.”

This clashed with the policies of various states, and after Jackson vetoed the renewal of the charter of the Second Bank of the United States, these states’ banks increased their printing and issuing of paper currency, without necessarily having the loot to back it up. The early 19th century also saw a pioneer-style real estate bubble, as speculators bought up Western land newly stolen from native people, using this paper money.

In 1836, Jackson issued an executive order requiring that people pay for government land in specie instead. As a result, paper money quickly lost value, and those who had been relying on it ran into trouble. Foreign investors began raising interest rates on American loans, hoping to get out before things got worse. On May 10th, 1837, banks in New York City announced that they would no longer trade paper banknotes for gold or silver, making them even more worthless. Thus began a seven-year recession, during which unemployment skyrocketed, banks shuttered, businesses were bankrupted, and entire fortunes crumpled away like the paper they were.

This banknote tells about the same story, but through the kind of surreal, nightmarish imagery only achievable in times of political crisis. It takes the form of a “shinplaster,” a kind of ad-hoc small bill primarily printed by merchants and other private entities. “Small bills were really important when you were paying workers, or trying to get your hair cut or buy a loaf of bread,” explains Jessica Lepler, an associate professor of history at the University of New Hampshire and the author of The Many Panics of 1837.

But even state banks didn’t issue bills smaller than $5, and thanks to the specie shortage, coins were hard to come by. To keep in business, barbers and shopowners drummed up their own local economies, issuing change in homemade shinplasters. “These shinplasters existed before the panic, and even more after,” says Lepler.

This particular shinplaster wasn’t worth anything. Instead, it was the equivalent of an editorial cartoon, meant to lampoon all the high-level decisions that had forced average Americans to print their own cash. It was drawn by an illustrator named Napoleon Sarony, and printed by H.R. Robinson, a staunch Whig who blamed a hard-money-loving Democratic faction, the Loco Focos, for the crisis.

Look closely at its weird populace, and you’ll see the caricatured faces of towering historical figures. That lady on the left side? “That’s Andrew Jackson in drag,” says Lepler. Jackson is dressed as Lady Liberty, and holding a knife that says “veto,” meant to remind everyone of that time he had vetoed the Second Bank of the United States. The cracked globe he is standing next to represents The Globe, the leading newspaper of his party. “It was kind of the Fox News of its time,” says Lepler.

Jackson also makes a second cameo on the right side, this time as an incontinent donkey. “He’s pooping out gold currency because that’s supposedly what he wants to happen to the money supply,” explains Lepler. His vice president and successor appears too: “Martin Van Buren, his little trained monkey, is collecting the poop in a top hat.” Van Buren was also widely maligned, both for sucking up to Jackson and for continuing his policies once he himself had taken office. (He was also considered overly stylish, which explains the top hat.)

It is also Van Buren’s face on the crazy dragon on the top of the note, hoarding bags of money and riding in a wagon labeled “Treasury Department.” The wagon is being pulled by Loco Focos, who in turn are being whipped by John C. Calhoun, an infamous Southern successionist who supported Jackson on economic issues, if very little else. The whole crowd is running roughshod over people in the street. “A lot of Democratic support came from working class men,” says Lepler. “They’re trampling them.”

And then there’s the dung beetle, sporting the small, determined face of Missouri senator Thomas Hart Benton. “Benton was known as Old Bullion Benton, because he was really in favor of hard currency,” says Lepler. “People called specie ‘Benton’s Mint Drops.’” The Benton bug is pushing a massive lump of dung, labeled with the banknote’s supposed value. Around him, in pompous script, loops a promise “to pay out of the United States Treasury, seven years after it is convenient, the amount of seventy-five cents.”

It’s difficult to consolidate a whole issue into an image, as evidenced by today’s one-panel political cartoons. As monstrous as this one looks, it’s actually pretty subtle, lampooning the country’s sad situation in its form—a useless piece of paper, dressed up as money—as well as its weird, weird content. As the Treasury Department begins to redesign our current American currency, they might want to consider a few more important financial players: flag drag Jackson, monkey Van Buren, and a certain human-faced, hard-money-loving dung beetle.

Object of Intrigue is a weekly column in which we investigate the story behind a curious item. Is there an object you want to see covered? Email ella@atlasobscura.com.

Update, 11/2/2016: This article has been edited to clarify facts related to the Panic of 1837.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook