The Bonkers Real-Life Plan to Drain the Mediterranean and Merge Africa and Europe

It’s not just the plot of a Philip K. Dick book—a man spent his life trying to make Atlantropa happen.

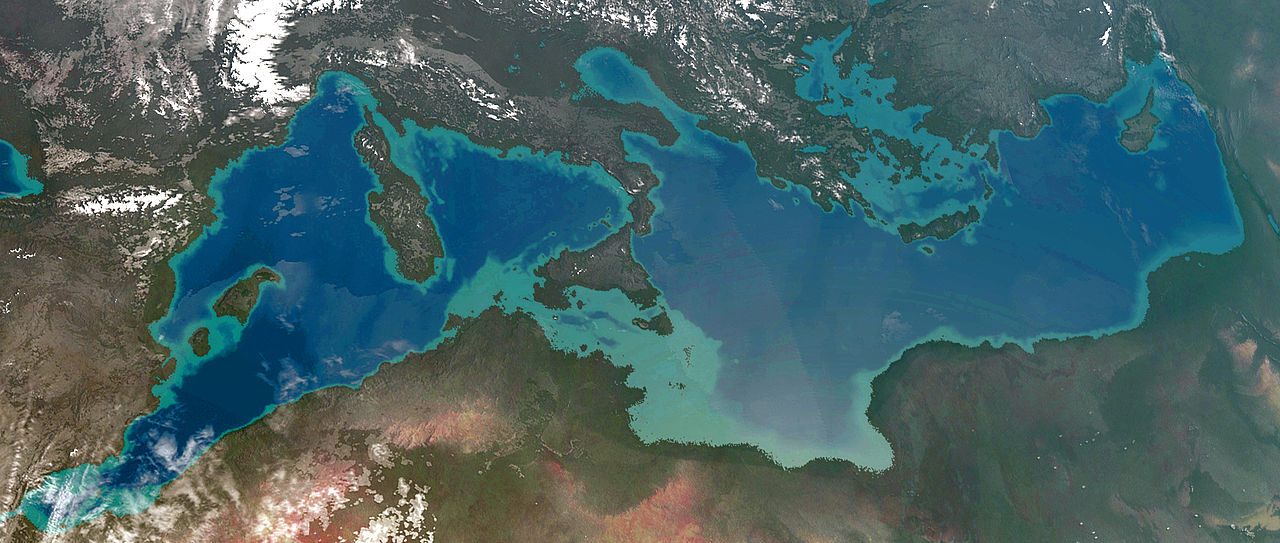

An artist’s rendering of what Atlantropa—a plan to partially drain the Mediterranean—might have looked like. (Photo: lttiz/CC BY 3.0)

Later this year, Amazon Studios will release the much-anticipated second season of The Man in the High Castle, a story set in a grim alternative future, where the Axis Powers have won World War II. The United States is cut up in three parts, with a Nazi puppet state in the east, a region under Japanese occupation in the west, and a neutral buffer zone between them. The series is loosely based on a sci-fi classic written by Philip K. Dick. In the original novel, published in 1962, Dick describes how the Axis Powers have drained the Mediterranean, in order to reclaim vast swaths of additional farmland.

The story is widely seen as an allegory on Fascism. But somehow, the most farfetched of this complicated plot is the one closest to reality: the part about emptying the Mediterranean.

In fact, the plan was a very seriously considered proposal, mapped out a few decades earlier by the German architect Herman Sörgel who devoted his whole life to promote his grand scheme to drain the Mediterranean and unite Europe and Africa into one super continent.

Herman Sörgel, in 1928, who conceived of Atlantropa. (Photo: Public Domain)

Back in 1929, Sörgel wrote a book on his ideas under the title The Panropa Project, Lowering the Mediterranean, Irrigating the Sahara. Three years later he rebranded his project in another book, called Atlantropa, the name by which his utopian project is still remembered. Persistence must have been one of Sörgels main character traits, because until his death in 1952, he kept on defending Atlantropa in four books, over a thousand publications and countless lectures, enough to fill up a special section in the archive of the Deutsches Museum in Munich.

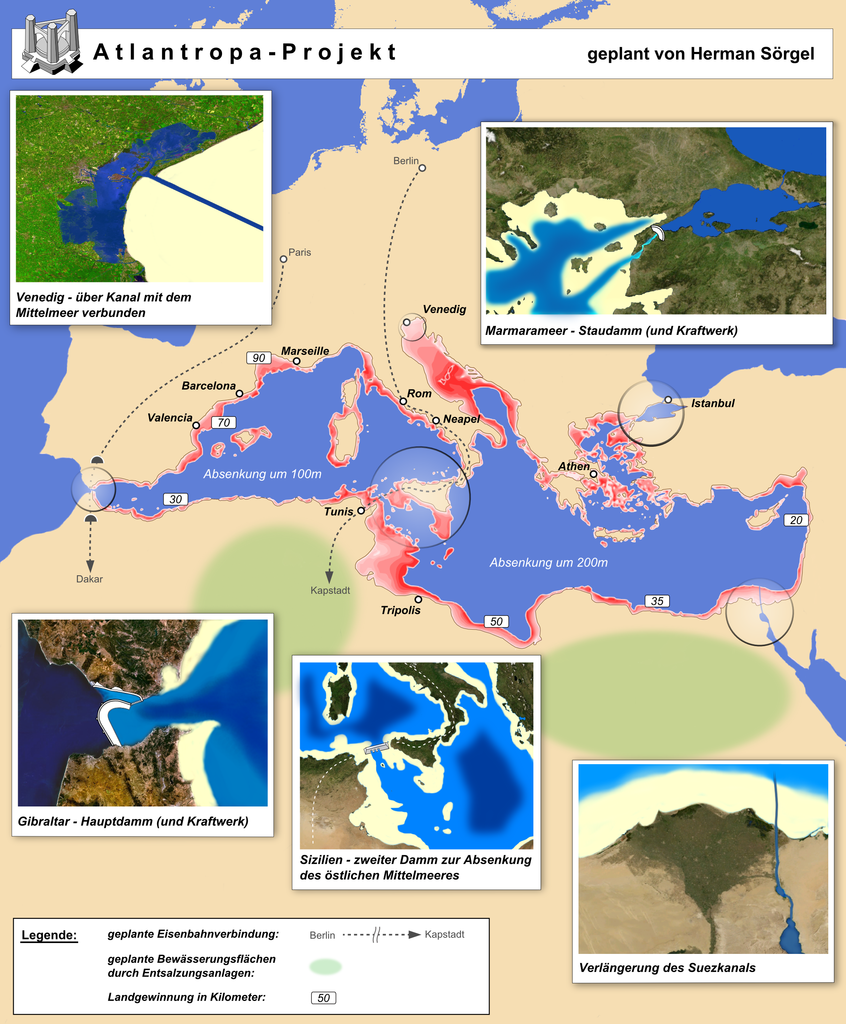

Not hampered by any sense of reality or modesty, Sörgel’s Atlantropa design envisioned three gigantic dams which dwarf contemporary superstructures like China’s Three Gorges Dam. The biggest barrage would be built across the Straits of Gibraltar between Spain and Morocco, separating the Mediterranean from the Atlantic Ocean. A second dam would block the Dardanelles and shut off the Black Sea. As if that were not enough, a third dam would stretch out between Sicily and Tunisia, cutting the Mediterranean in two, with different water levels on either side.

The Mediterranean is fed by several rivers, but the main body of water flows in from the Atlantic Ocean, so lowering the sea level would not have been a difficult task, once the Straits of Gibraltar had been sealed off. The benefits of Atlantropa were numerous, according to Sörgel and his followers. Each of the dams could provide enormous amounts of hydroelectric energy, supplying Europe with all the electricity needed. Lower sea levels would create vast stretches of new farm land along the current coastline, offering Europe’s nations space to expand.

A central component of Atlantropa was to dam the Straits of Gibraltar, shown here from a satellite. (Photo: ESA/NASA)

As weird as it sounds, Atlantropa was Sörgel’s answer to the doom and the gloom that clouded over Europe after the First World War. Mass unemployment, poverty and bitter strife between Europe’s leading nations made the future look dark and uncertain. Sörgel shared the worries of his time and looked for answers, not only for Germany, but for the whole of Europe. Being an avid pacifist, Sörgel claimed that building Atlantropa would guide Europe into a brighter future, away from war and poverty. Because of its scale, Atlantropa required cooperation between countries, creating an interdependence that would rule out future armed conflicts. The amount of labor required to build Atlantropa could keep the unemployed masses busy for decades, and cheap energy would boost the economy to unprecedented levels of growth.

The German public loved the plan. Media doted on Sörgel, and he attracted a fair share of followers. He founded the Atlantropa Institute to promote his visionary worldscape.

But despite the idea’s popularity and the tireless efforts of Sörgel, Atlantropa never took off.

A map showing the location of various Atlantropa projects. (Photo: Devilm25/CC BY 3.0)

Once the Nazis seized power in Germany, Sörgel took the idea to them. But unlike Philip K. Dick’s novel, the new rulers were not interested in building dams. Instead, the Nazis looked to conquer the much-needed Lebensraum the old-fashioned way, by invading and occupying neighboring countries. The Allies briefly picked up the idea after the defeat of the Third Reich, but quickly dismissed it as completely unrealistic, especially given the fact that Europe needed to be rebuilt. The rise of nuclear power diminished the appeal of hydroelectricity as well.

Although the Atlantropa Institute lingered on until 1960, Atlantropa died with Sörgel in 1952. But the idea lived on, not in the minds of ambitious engineers, but as a science fiction theme. The Man in the High Castle is just one example. In his novel The Flying Station, Soviet sci-fi writer Grigory Grebnev imagines yet another alternative future where not the Axis Powers but the Socialist Revolution has triumphed and build the dam. In Grebnev’s story, a small band of Nazis conspires to destroy this glorious achievement of the revolution from their hideout at the North Pole. And Gene Roddenberry’s book version of Star Trek depicts Captain Kirk standing on a huge dam in the Straits of Gibraltar. It might only be a scant comfort to Sörgel, but his dream dam lived on in a fictional universe.

Update 9/30: An earlier version of this story mixed up how the U.S. was partitioned in ‘The Man in High Castle.’ The Nazi state was on the East Coast, not West; Japan occupied the West Coast; not East. We regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook