Counterfeit Paris & Other Fake Cities Built in the Name of Espionage

Plaque marking a London zeppelin raid from 1915 (photograph by Christoph Braun/Wikimedia)

Plaque marking a London zeppelin raid from 1915 (photograph by Christoph Braun/Wikimedia)

Whether it was the terrifying drone of a German heavy bomber or the near-silent hum of a zeppelin, since the beginning of WWI when bombs fell on civilian targets far from the Front, the threat of death from the skies has been very real during times of war. But the art of war is not just in the power of destruction, it is also in methods of confusion and subterfuge.

From January of 1915 until the end of the First World War, German dirigibles made around 51 bombing runs against Great Britain – which led to more than 500 deaths. Although these bombings are often focused on by historians, the Belgian cities of Leige and Antwerp were both bombed in 1914, as was Paris (although Paris received more than the standard incendiary bombs, they were also bombed with leaflets, demanding the French surrender). Originally the German Kaiser, Willhelm II, forbade bombing strikes against London, as the King and Queen of England were his close relatives (he was the eldest grandson of Queen Victoria), although on seeing the immense psychological damage these raids had on the British, the Kaiser complied with the advice of his generals, and London became a target.

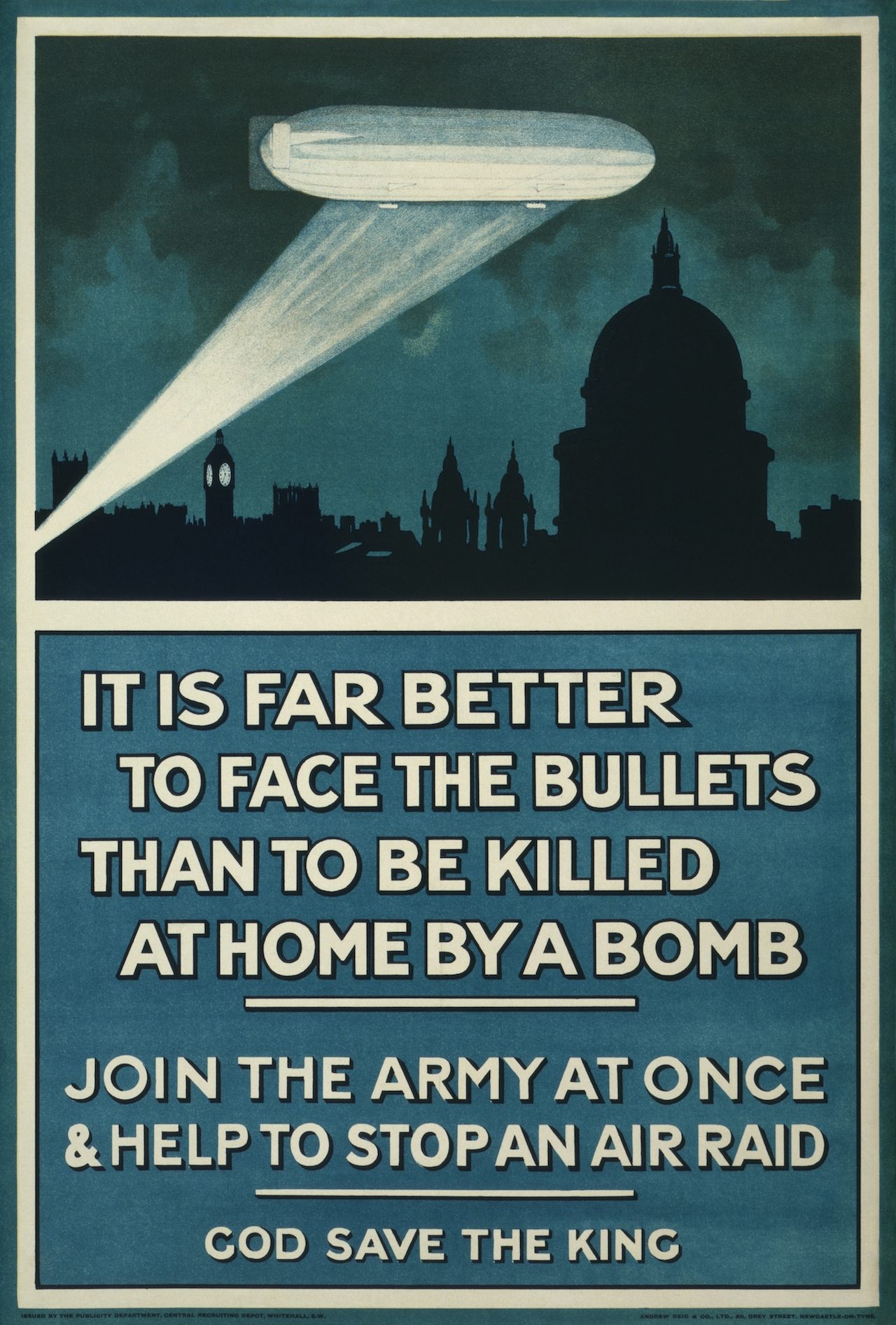

“It is far better to face the bullets than to be killed at home by a bomb. Join the army at once and help to stop an air raid. God save the King” (1915 poster) (via Library of Congress)

“It is far better to face the bullets than to be killed at home by a bomb. Join the army at once and help to stop an air raid. God save the King” (1915 poster) (via Library of Congress)

At first there was little that could be done against the silent menace of dirigibles, as the ground-based anti-aircraft weapons of the time did not have the range required to hit them, and those weapons that could be mounted on interceptor-aircraft had little effect on the flying behemoths.

Alternate methods of defense were required.

Engineers in Britain and France were redirected from the efforts of the land-war, which in itself was a victory for the German High Command, as the damage caused by the dirigible raids was, in fact, negligible. Devices such as the acoustic mirror and incendiary bullets were invented, but it was perhaps the French who came up with the most elaborate solution: an artificial Paris, designed to be built on the city’s northern outskirts.

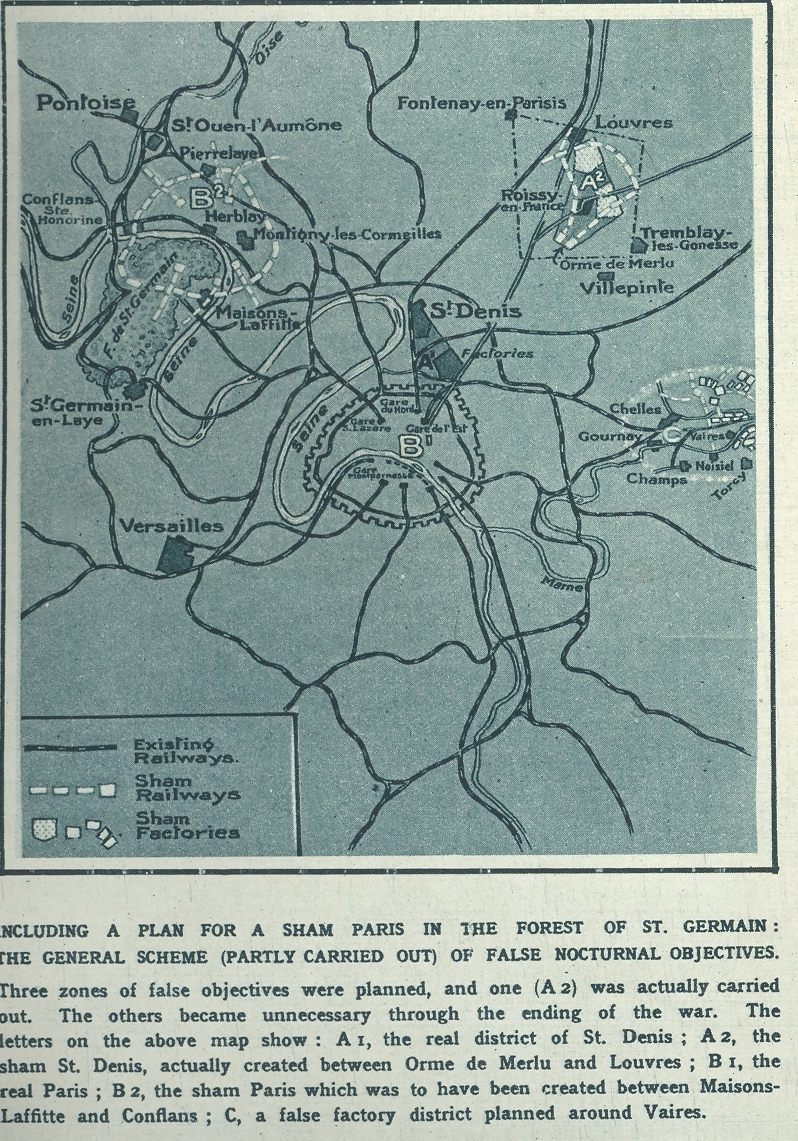

The town of Maisons-Laffitte north of Paris, was the focal point of the French military’s efforts to protect Paris from German bombing runs, although three more sites were planned, surrounding the capital. It sat on a stretch of the Seine that closely resembles the river as it passes through Paris, some 15 miles to the south. Built mostly of wood and canvas, a team of artists was hired to paint the city, and the electrical engineer Fernand Jacopozzi (famous for first lighting the Eiffel Tower), was brought in to make Faux Paris more appealing to the German bombers.

A map of Faux Paris (via JF Ptak Science Books, which has more images of the “Second Paris” on their site)

A map of Faux Paris (via JF Ptak Science Books, which has more images of the “Second Paris” on their site)

Although only a small fraction of the fake city was ever completed, it had running trains, as well as replicas of the Arc de Triomphe and the Champs-Élysées. It had working lights (just dim enough to convince the Germans that the French had closed their curtains to disguise the city), and industrial sectors, with a translucent paint applied to the roofs to mimic dirty glass ceilings. The partly-built city was never attacked, and quickly disassembled at the end of the war. The Germans were, apparently, developing similar plans for their industrial bases, but the war ended before those plans could be put into action.

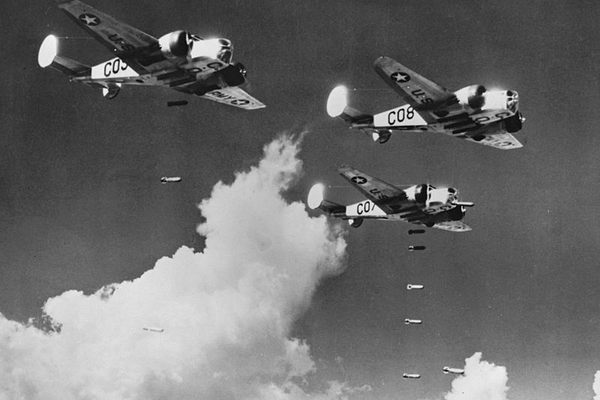

In the Second World War, German bombing raids on England intensified. Almost nightly, the Luftwaffe’s bombers droned above London, and although the anti-aircraft weapons were much more powerful than during the First World War, so too were the aircraft. The Battle of Britain raged in the skies, with more than 90,000 civilian casualties. The British authorities needed to not only protect their military assets, but also to protect the people from German bombings. They borrowed the plans of the French, whether deliberately or through convergent evolution.

Around the United Kingdom, various potential targets were identified, focused primarily on military hardware, with false tanks, aircraft, and factories constructed to fool German bombing raids. After the bombing of Coventry, however, they expanded this project with the construction of Q-sites.

Q-sites were built within four miles of potential target cities, and were laid out to simulate blacked-out towns, with fires being lit in the Q-sites after the first wave of bombs were dropped on the target towns. It is estimated that more than 900 tons of munitions were wasted on these sites. The concept of blacking-out towns across Britain saved countless lives, as in the days before reliable aircraft navigation aids and techniques, pilots and their crew needed to see their targets or local landmarks. In fact, some of the most lethal German pilots were those who had studied or holidayed in Britain before the war, as they knew both the locations of culturally important sites, and the potential psychological damage that could be inflicted through longterm bombing these places.

It wasn’t only the British who got caught up in the building of fake towns After the raid on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, industrial sites along the West Coast were disguised as non-military sites. Boeing’s B17 Bomber factory in Seattle, for instance, was covered with 26 acres of suburban streets, such as the charmingly named Synthetic Street. Actors were hired to walk on the rooftop, hanging laundry, and engaging in other wholesome 1930s behaviors. (Photographs can be found here.)

A soldier with an inflatable three-ton lorry in WWII (via Imperial War Museums)

A soldier with an inflatable three-ton lorry in WWII (via Imperial War Museums)

An inflatable Sherman tank from WWII (via Imperial War Museums)

An inflatable Sherman tank from WWII (via Imperial War Museums)

During the Second World War, the Allies deployed the so-called Ghost Army to France in the wake of the D-Day invasion. The Ghost Army (or, officially, the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops) was an Allied unit that moved through France sowing misinformation and generally confusing the enemy. Made up primarily of actors, artists, engineers, and advertisers, they operated near to enemy lines, and deployed inflatable tanks, dummy airfields, troop emplacements, and artillery formations. Alongside these visual props were recordings of troops and vehicles rumbling, and the Ghost Army filled the airwaves with false radio chatter, as well as imitating other Allied units’ insignia and ranks to further deceive the Germans.

Even earlier in the war, particularly in North Africa, British forces employed deception as a tactic against the famous General Rommel, building fake railway stations and supply columns — these efforts led directly to Operations Bodyguard, Titanic, and Glimmer, which in turn convinced the German military that the Normandy landings were the deception, and diverted a significant portion of German manpower away from the landing sites at Normandy for a staggering seven weeks.

Dummy paratrooper used in D-Day, which included machine gune fire simulators & self-destroying charges (photograph by Pajx/Wikimedia)

Dummy paratrooper used in D-Day, which included machine gune fire simulators & self-destroying charges (photograph by Pajx/Wikimedia)

During the Vietnam War, fought from the early 1960s until the fall of Saigon in 1975*, the Viet Cong were also known to make use of artificial villages to protect their tunnel complexes, and false tunnels, to distract American and Australian soldiers and consume valuable operations time. These tunnel complexes could be, well, incredibly complex, with some of the larger ones not only featuring bunkers and weapons depots, but also political re-education schools, command centers, hospitals, and even theaters (for the production of politically educational plays, no doubt.) The most elaborate of these tunnel systems ran for miles, and often needed to be flushed out by the so-called “tunnel rats,” men who were often the physically smallest soldiers in their units, who crawled through the underground passages armed with only pistols and flashlights.

Although WWI saw the first mass production of artificial cities to confuse the enemy, there are also the (alleged) historical example of Grigory Potemkin, who built artificial villages in the 18th century to fool his Empress. After the Russian conquest of Crimea in the 1780s, Tsarina Catherine the Great appointed Potemkin as the region’s governor, tasked with rebuilding the shattered countryside. Although the story may be apocryphal, it is said that Potemkin’s men assembled villages along the river where Catherine’s barge drifted, and acted out the roles of peasants until the Tsarina passed along. The village would be quickly disassembled, and rebuilt further downstream to continue the deception.

North Korea’s Kijong-dong, aka “Propaganda Village” (photograph by Don Sutherland, U.S. Air Force)

North Korea’s Kijong-dong, aka “Propaganda Village” (photograph by Don Sutherland, U.S. Air Force)

Possibly the most famous “Potemkin village” in the world is that of Kijong-dong, in North Korea, which, according to the North Korean government, is home to a collective-farm, worked by 200 families, as well as the world’s third largest flagpole(!). The rest of the world disagrees, and observation through telescopic lenses reveals that the city is uninhabited, and that none of the buildings are anything more than concrete shells, with automated lighting systems and cultivated fields around the site striving to add to the illusion.

In 2010, it was reported that the Russian government had purchased a large number of inflatable planes and tanks, in order to disguise the deployment of its military hardware. Even though we live now in a world where it seems that everything is observed and under question, at least two countries think we can still be fooled through such simple deceptions.

* Correction: This article originally stated that the Fall of Saigon took place in 1973. It was 1975.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook