The Epic Century-Long English Battle to Rid Itself of American Squirrels

The American Revolution looks easy compared to the problem of grey squirrels.

They’re aggressive. They’re big. They’re stealing resources from the natives, they carry disease. They cost Britain millions of pounds a year and they’re breeding.

And they’re squirrels.

You’d be forgiven if you thought that sounded like a xenophobic rant against foreign invaders. But it’s a mark of just how heated—and how strange—the debate over the fates of two photogenic rodents, the introduced North American grey squirrel and the native red squirrel, has become in Britain.

North American grey squirrels first entered Britain as pets for the upper classes in the Victorian era, but it wasn’t until 1876 that they escaped their cages. The story goes that Thomas Unett Brocklehurst, master of Henbury Hall in Cheshire and world traveler, brought a pair of grey squirrels to this tiny island because he thought they’d look nice gamboling around on his estate. That’s the story, but the historic record isn’t clear on whether Brocklehurst really did bring the squirrels—the current owners of Henbury Hall have no record of anything pertaining to squirrels and the local historical society doesn’t either. If Brocklehurst was indeed the man, he was also something of a trendsetter. Several years after Brocklehurst, the 11th Duke of Bedford, Herbrand Russell, reportedly brought 10 pairs of the fecund little animals from New Jersey and released them onto his estate, Woburn Abbey in Bedfordshire. Russell, ironically the president of the Zoological Society of London and a keen supporter of animal conservation, was instrumental in distributing grey squirrels around the country: He set them loose in Regents Park and Kew Gardens in London and gifted them to squirrel-less friends. The population of grey squirrels, sturdy of body, chattering and robust, steadily rose.

“This is entrepreneurial Britain, so these guys hadn’t got anything to do with their money,” says Adrian Vass, Squirrel Accord manager for the Forestry Commission and red squirrel supporter, explaining that importing rare breeds of arboreal rodents was a kind of status symbol. “And of course they didn’t realize what would happen.”

Thomas Unett Brocklehurst, master of Henbury Hall, pictured, reportedly introduced grey squirrels to the UK. (Photo: Viewfinder/CC BY-SA 4.0)

What happened was that as the population of these furry lawn ornaments increased, the native red squirrels declined. Rapidly.

The grey squirrel, as it turns out, is a tremendously successful introduced species. Larger than its European cousin, it eats more and has been known to dig up red squirrels’ caches of seeds and nuts. The grey also has the ability to digest the unripe seeds of broadleaf trees, such as the oak; red squirrels can’t, and so when it comes time for them to harvest seeds later in the season, there aren’t many left. The greys live in higher population densities, crowding out the reds, and even though the grey male cannot mate with the red female, they’ve been known to scare off would-be red suitors. According to the UK government, they carry the squirrel poxvirus, a disease that has little effect on them but is lethal to red squirrels. And though much of the wide geographic distribution of grey squirrels can be attributed to squirrel-spreading Victorian gentlemen, they are also keen explorers themselves and will frequently seek out new territory to colonize. “I always think they’re a bit like a Roman legion,” says Vass, of the grey squirrels’ impulse to seek new areas. “They have their scouts, the youngsters go out and check what habitat is ahead of them and they then pass those messages back to the cohort behind them.… I think they’re enormously efficient, they’re lightyears ahead of red squirrels.”

Within 50 years of Brocklehurst’s alleged introduction, the grey squirrels had made it as far as Wales; people had long noticed that where there were grey squirrels, there weren’t red. In July 1928, the UK Forestry Commission investigated the squirrel situation; an offended New York Times reported in November of that year, under the headline “American Squirrel on Trial for His Life in England”, that the grey squirrel was the victim of a “crusade” against him. By 1932, the crusade had succeeded: Releasing grey squirrels in the UK became illegal; in 1937, failure to report a grey squirrel sighting was punishable by a £5 fine (the law remained on the books until 2014). But unenforceable laws did little to limit the impact of the grey squirrels’ introduction, and even the bounty on grey squirrels’ heads (or tails, rather), half a shilling eventually raised to 2, couldn’t stop their spread.

A red squirrel spotted in Scotland. (Photo: Peter G W Jones/CC BY-ND 2.0)

Now, upwards of 3 million grey squirrels live in the UK, having taken over southern England; roughly 160,000 red squirrels remain, holdouts primarily in northern England and Scotland where grey squirrels are less prevalent. In a video made by the Red Squirrel Survival Trust titled “The Red Squirrel: A Legacy for the Future” and narrated by Alan Titchmarsh, Britain’s favorite television gardener, red squirrel supporters make it unequivocally clear: “The red squirrel’s problem is the grey squirrel.” Without intervention, they say, the red squirrel could disappear completely within 15 years.

In 2014, Prince Charles, one of the country’s most outspoken conservationists, decided that it was time to do something about the squirrel problem. He invited a cohort of 35 woodland, timber industry and conservation organizations to form the Squirrel Accord. The Accord acts a kind of central clearinghouse, coordinating the efforts taking place across the UK to “control the grey squirrel population” and save the reds; Vass is the Accord coordinator for the Forestry Commission. The Squirrel Accord doesn’t exactly shy away from the fact that “control” largely means killing, but it doesn’t exactly spell it out, either.

And this is where things get messy. To start with, the language used by some red squirrel supporters comes across as unnecessarily martial at best, and at worst, chillingly xenophobic, and protectionist. From the beginning, how people talked about the squirrels was clouded by patriotism bordering on nationalism. In the 1920s, for example, one government official was quoted in the Times of London calling them “sneaking, thieving, fascinating little alien villains.” In the 1930s, after it became an offense to release the squirrels, headlines decried the “alien pest”, and even now, many publications label the greys a “plague” and an “invasion”.

A “slow for red squirrels” sign in Southport, near Liverpool. (Photo: David Hawgood/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Though many squirrel supporters shy away from uncomfortable words like “eradication”, some red squirrel supporters embrace it. In 2007, a New York Times Magazine article painted Rupert Mitford, the 6th Baron Redesdale and a prominent red squirrel supporter, as a trigger-happy, old-moneyed relic, gleefully massacring the greys in an ecological cleansing and chortling over their deaths; a 2008 Guardian story did nothing to ameliorate this image when it quoted Mitford saying, “We only call ourselves the Red Squirrel Protection Partnership because if we called it the Grey Squirrel Annihilation League people might be a bit less sympathetic.” Other vocal red squirrel supporters use the language of protectionism to great effect. In 2012, Janice Atkinson-Small, a director of a center-right thinktank called WomenOn “which seeks to challenge the left dominated Guardianista feminist view of the world of women”, declared in an op-ed for The Daily Mail, “If there was a band of illegal immigrants that cost our economy an estimated £14m per annum, carried a fatal disease that killed off most of the indigenous population and threatened our wildlife and woodlands too, wouldn’t you be keen to go to war with them?”

While there is no data to support the idea that people who champion red squirrel conservation also ascribe to right-leaning political views—and Mitford, for example, is a Liberal Democrat, a center to center-left party—there are some uncomfortable correlations.

An alert for red squirrels in the south of England. (Photo: Mike Russell/CC BY 2.0)

“It does sound remarkably like Donald Trump, doesn’t it? ‘We should build a wall and we should make those grey squirrels pay for it,’” jokes Hugh Warwick, an ecologist, hedgehog champion, and writer for The Guardian. Warwick has written in the past about the problems with pitting the squirrels against one another and he’s not the only one: In 2006, journalist Tim Luckhurst wrote in The Sunday Times, “Squirrels cannot speak. But I fear that if they could the newcomers would be entitled to ask: ‘Is it because my fur is grey?’ After all, being immune to a killer virus, adapting to the local habitat and thriving on available food are all evidence of evolutionary success. To accuse them of spreading disease sounds like a classic anti-immigrant slur.” In 2012, Chris Packham, a popular BBC wildlife program presenter, accused red squirrel conservationists of having “lost the plot when it comes to purity and perfection”, and declaring them “a small band of lunatics who are insidiously bogged down and blinded by sentimental racism”. After the signing of the 2014 Squirrel Accord, journalist Oscar Rickett accused Prince Charles, who has conducted several grey squirrel culls on his vast Duchy land holdings, of dressing nostalgia up as environmentalism and “battling furiously against a rising tide of change, much of it entirely imagined”.

“We do have this sort of feeling that there was a time that it was better,” says Warwick, about the kind of nostalgia supporters of the red squirrel evoke. “But the grey squirrel is now part of our ecosystem. The point is they’ve been here for a good long time, they’ve settled themselves in. If we’re saying, ‘Right, we don’t want grey squirrels,’ what else are we going to say we don’t want?”

Grey squirrels in Richmond Park, London. (Photo: Alex Groundwater/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Warwick doesn’t count himself as a grey squirrel champion, exactly—he accepts that killing the grey squirrels might, in the end, be the only way to rebalance the British landscape. But he also notes that for many urban people, grey squirrels are their first contact with real wildlife. And that’s important. “For someone who doesn’t have much opportunity to see wildlife, my goodness, it’s wildlife,” he says. Grey squirrels, with their ubiquity and the fact that it’s really funny watching them try to extract food from feeders in the shape of horse’s heads, are a “gateway” animal: “You get to close to wildlife, you form a much more intense bond… if you get lucky, or the natural world gets lucky, you might just love them. Squirrels, love them or hate them, they’re a way in.”

The grey squirrels do have other defenders, although they are far less politically connected as the Prince of Wales. Angus MacMillan and his son, Neil, both of Glasgow, are Professor Acorn, a chipper grey squirrel with a website trying to counteract the negative PR campaign battering the “alien” squirrels’ image. They say that first and foremost, killing grey squirrels is cruel. “Although they say they destroy them humanely, it’s really not humane,” says Angus MacMillan, noting that many squirrels are live trapped and then hit on the head with a blunt instrument. The first blow doesn’t always do the job. But the MacMillans also object to the overtly protectionist nature of supporting red squirrels over greys. “I know there is a great difference between humans and animals—or is there?—but the sort of general policies denote racism,” he says. “They’re killing [grey squirrels] because they come from another country, I don’t accept that.”

The title page from Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin. (Photo: Public Domain)

The image of the animals in popular culture has been shaped as much by fiction as lived experience. People on all sides of the squirrel debate blame Beatrix Potter and her twee Windermere fauna for shifting opinions on the squirrel: Potter created an anthropomorphic universe in which rabbits wear jackets (but no trousers), hedgehogs do laundry, and Squirrel Nutkin, with his rust-colored fur and flame-tipped ears, is the embodiment of cheeky charisma. (Notably, Potter also penned a story about Timmy Tiptoes, a grey squirrel who is accused of being a nut thief; Timmy wasn’t then and isn’t now as popular as Nutkin.) Squirrel Nutkin gave the red squirrel a personality, but he also cemented the red squirrel’s place in British imagination; when the squirrel’s actual place in the British landscape came under threat, affection helped propel the squirrel’s cause to the front pages of newspapers. And it does make an easy, good story: The plight of the red squirrels was even explicitly referenced in the 1940s—a time when the country’s very way of life was under ferocious attack—in A Squirrel Called Rufus, the story of the brave red squirrel defending his homeland against the evil invading greys. That, in many ways, is the same story some supporters of the red squirrel still tell.

So what is it? Racist thinking ported to small mammals or a genuine environmental problem? Unfortunately, the emotionally-charged debate can obscure even basic facts. For example, the numbers of red and grey squirrels are reported with surprising variety—the Forestry Commission says there are 140,000 to 160,000 red squirrels in the whole of the UK, versus around 2.5 to 3 million grey squirrels. But the Conservative Telegraph, possibly accidentally, puts the numbers of red squirrels at only around 15,000 in the whole of the UK, and right-leaning Daily Mail puts the numbers of grey squirrel much, much higher, around 5 million—both might be guilty of overestimating the threat.

The real reason why the Forestry Commission, for example, wants to reduce the invasive grey squirrel population might not even have anything to do with the native animals. “The UK Squirrel Accord and our supporters are not driven in any way by ‘sentimental racism’ and it is really nonsense to suggest this,” Vass later clarified in an email. “The need to control grey squirrel numbers in the United Kingdom is driven by economic factors.” According to him, the damage to rooftops caused by greys tops £20 million and the horticultural pain is “impossible to calculate in absolute financial terms.” Then there’s the not-so-silent other victim: Songbirds, whose eggs are destroyed or eaten by squirrels.

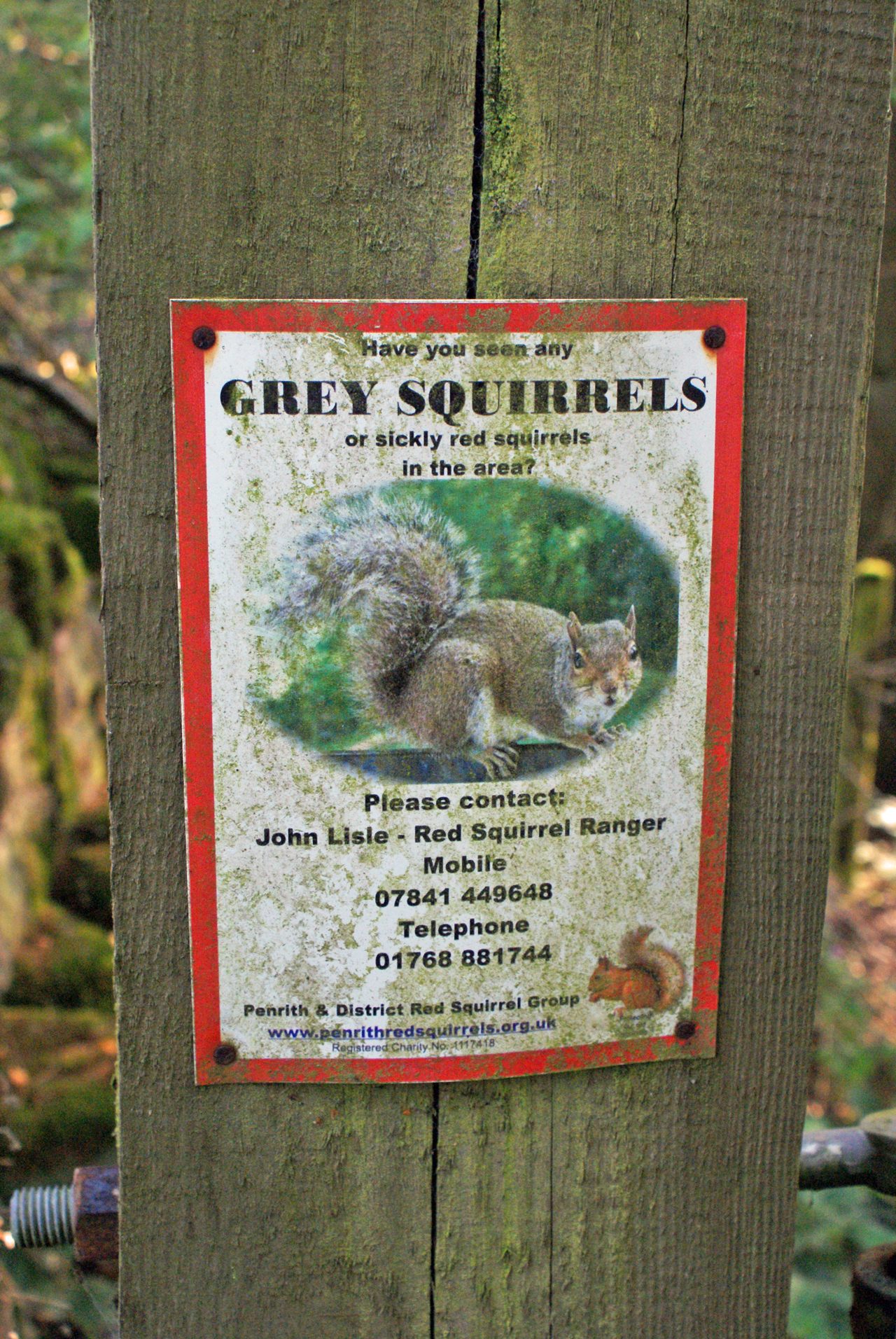

A notice from the Penrith and District Red Squirrel Group for sightings of grey squirrels or sickly red squirrels. (Photo: Richard Dorrell/CC BY-SA 2.0)

But perhaps the most significant victim is the trees. The government’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and others agree that the grey is responsible for a significant amount of damage to the broadleaf trees through what’s called “ring barking”. Squirrels strip the bark off trees in bands, creating open wounds prone to infection; between 35 to 40 percent of the broadleaf tree population is affected, resulting in some cases in the death of the tree. This destruction puts in danger the government’s promise to meet the international Biodiversity 2020 target, an agreement to halt the loss of biodiversity by that year, but perhaps more importantly, it has huge negative consequences for the native timber industry, including as much as £14 million a year in damage. Says Vass, “It’s not really about eradicating a grey mammalian species, it’s about managing the damage they do to trees.”

Vass and the Squirrel Accord advocate alternatives to culling, such as contraception for squirrels; other recent research shows that the introduction of the pine marten, another threatened native species and a predator that kills squirrels, has resulted in the decrease of grey squirrel numbers and a stabilization of red squirrels. This all gives hope that there might be a more ecologically, emotionally comfortable way to curb the grey population. But that doesn’t satisfy the MacMillans—they believe that the only thing to do about the squirrels is nothing: “I think we should be leaving these animals alone and the populations will sort themselves out,” says Angus MacMillan. Asked whether we have a duty to “fix” the situation, MacMillan responds, “In a word, no.”

The MacMillans are outliers, but they’re not lonely. A recent rash of books—Where Does the Camel Belong? by plant biologist Ken Thompson and The New Wild by journalist Fred Pearce—suggest that invasive species might not be so “invasive” after all. In their paper, “The Rise and Fall of Biotic Nativeness”, Matthew Chew and Andrew Hamilton of Arizona State University’s School of Life Sciences dismantle the notion of “nativeness” all together, exploring how place, time, naming, and even human preference combine to create a kind of false authority. “None of the relationships comprising biotic nativeness is an inevitable, permanent or dependable object supporting a conception of belonging,” he and his fellow researchers concluded. “Nativeness” is outmoded.

The introduction of Pine Martens may have reduced grey squirrel numbers. (Photo: Peter G W Jones/CC BY-ND 2.0)

Warwick isn’t exactly a proponent of the native-as-construct concept, but he agrees that supporting red squirrels over grey squirrels is a somewhat arbitrary decision. “Where are we going to draw the line about what is a native species?” he asks. “At what point in our history are we saying that is the eco system we want in this country?” That perspective highlights just how bound up in emotion and perception the debate about the squirrels, like any debate about an “invasive” species, is.

For the moment, the future of the red squirrel is tentatively positive. In 2015, newspapers thrilled to the news that red squirrel sightings were on the rise in the northern part of the country: “’Squirrel Nutkin’ fights back in battle against grey rivals”, cheered The Telegraph, while The Mirror crowed, “UK natives fighting ‘plague’ of greys”. The Isle of Wight and Anglesey have both seen success in encouraging the red, although by destroying the grey population. There’s even talk of reds naturally acquiring an immunity to the pox virus, as well as a pox virus vaccine that could protect them from the lethal infection.

A grey and a red squirrel on a tree stump in Cumbria. (Photo: Peter Trimming/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Meanwhile, the numbers of grey squirrels don’t seem to be shifting too much, despite a series of highly publicized and controversial culls. Intermittent efforts to get the grey squirrels out of the trees and onto British plates have also been met with resistance (they don’t, it seems, have very much meat on them or taste very good). That said, in September 2015, the Red Squirrels United group received £1.2 million in money from the national lottery to continue their preservation efforts, which in part means killing grey squirrels where they are likely to directly threaten the red.

As with most things, there are no easy answers on the squirrel question. Says Warwick, “These systems are complicated. The take-home message from the whole squirrel issue is simply that it is complicated.”

For the foreseeable future, at least, squirrels will be squirrels and the people who champion them, will be people.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook