In Pre-WWII Berlin, the Shape of Your Roof Was a Highly Political Decision

Modernists favored flat roofs, while conservatives preferred them pitched. They collided on a single street in the capital.

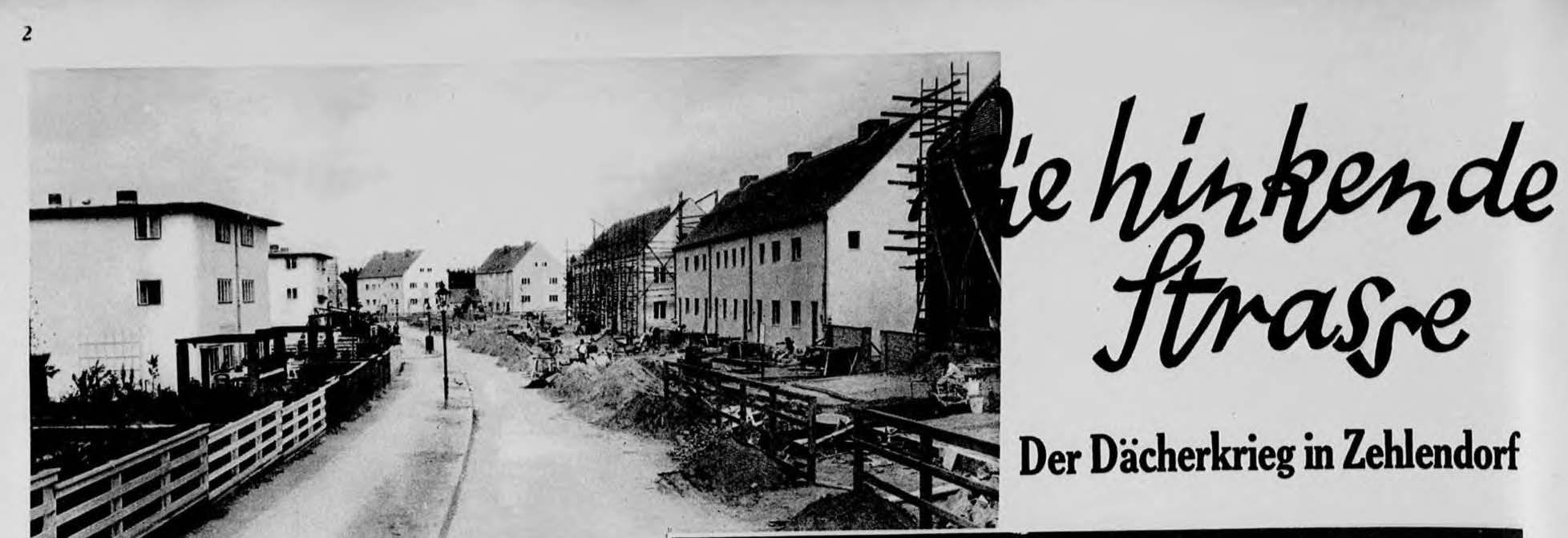

Sharp observers will notice something strange about the attractive residences lining Am Fischtal, a bucolic street in the Zehlendorf section of Berlin. On one side, the buildings have flat roofs, while on the other they are pitched: a situation that is less architectural happenstance than the result of a so-called “roof war,” waged in the Weimar Republic and which embodied many of the deeper conflicts that roiled Germany in the years before the Nazis came to power.

Flat roof advocates argued in the 1920s that they were less expensive to build and maintain, in addition to fitting in with Modernist ideas about minimalism and functionality, like using roofs as terraces. But the pitched roof partisans—including many nationalists—argued something entirely different: that flat roofs were a blight on traditional German architecture, or, as the critic Paul Schultze-Naumburg wrote, “immediately recognizable as the child of other skies and other blood.” Other critics were more explicit. The architect Paul Bonatz, for one, said that flat roofs bear “more resemblance to a suburb of Jerusalem than to a group of homes in Stuttgart.”

The two sides met on Am Fischtal, which today survives as a literal and figurative monument to the Weimar Republic’s increasing political divide. The flat roof residences came first, part of a housing development built by a leftist housing cooperative between 1926 and 1932 known as Onkel Toms Hütte, or Uncle Tom’s Cabin, an unlikely moniker borrowed from a nearby tavern which was named after the Harriet Beecher Stowe novel. Across the street, GAGFAH, a housing cooperative supported by conservative white collar unions, built their response in 1928: a community called Fischtalgrund, which consists of 30 buildings with 120 housing units. The roofs, of course, were pitched.

“What happened in 1928 in the quiet Berlin forest suburb,” Bruno Taut, the architect who designed Onkel Toms Hütte later wrote, “was like an omen of that which all Germans experienced in 1933”—when the Nazis came to power.

Before residents moved in, Fischtalgrund opened first as an exhibition in September and October 1928, its location inspiring the press to run stories about the “Zehlendorf Roof War,” and, indeed, it made good copy. The public, also, was interested: a year earlier, a flat roof housing development built in Stuttgart attracted nearly 500,000 people during an exhibition, in the process casting a spotlight on flat roofs.

But for the architects involved, the debate was more nuanced. Heinrich Tessenow, the lead architect behind Fischtalgrund, publicly rejected the idea of a war.

“Here as there, this is essentially a serious search for the best architectural solutions,” he said then. Meanwhile, the architect Walter Gropius, a well-known flat roofer and ostensibly Tessenow’s opposition, insisted “the question of whether a roof is flat or pitched is to be answered solely on the basis of practicality, technology, and efficiency. It is a mistake to make it a religious symbol, as is the case in the battle around the new architecture today.”

Still, such conciliatory comments were often downplayed or ignored in press reports, and, symbolically, the roof debate evolved as a proxy for the fight over Germany’s future.

On Am Fischtal, it was the flat roofers who struck the opening blow. Onkel Toms Hütte was developed by GEHAG, a cooperative housing corporation owned by blue collar unions with left-wing political affiliations that, during the 1920s, was one of the leaders in creating better housing for Berlin workers, who up until that time typically lived in crowded and unsanitary tenements called rental barracks.

GEHAG had hired Bruno Taut to be its chief architect in 1924. Although not well remembered today, Taut was a part of a group, including Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Le Corbusier, who popularized Modernist architecture in Europe during the 1920s. At Onkel Toms Hütte, Taut led a team of architects in creating a new community of approximately 1,900 housing units in colorful rowhouses and small apartment buildings with flat roofs spread across several blocks.

And in 1926, just as Onkel Toms Hütte began construction, the roof debate intensified, prompting GAGFAH to scramble a response, which would turn out to be Fischtalgrund, in which 17 architects designed new houses and small apartment buildings, all with pitched roofs. To lead their effort, GAGFAH chose Tessenow, an architect who used traditional designs but also emphasized that “the best is always simple,” an approach similar to Modernist thinking. While the political debates raged, in other words, the architects working on Am Fischtal were never that far apart.

Today, Onkel Toms Hütte celebrates its architectural legacy and in particular Taut, who left Germany when the Nazis came to power and died in 1938 while working in Turkey. There is a monument dedicated to him in the community, while the roof war itself is also commemorated by an interpretive sign on Am Fischtal.

Karl Kiem, a German architectural historian, argues that apart from their contrasting roofs, the two developments share many similarities, such as their human scale and balance between built form and landscape. The roof war is a reminder of a divisive past, but flat and pitched roofs have co-existed for nearly 90 years and together they form a listed historic district, suggesting that now Am Fischtal is a symbol of harmony, not conflict.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook