The History of GeoWorks, Microsoft Windows’ Upstart ’90s Competitor

AOL’s also involved.

A Commodore 64 computer. (Photo: Luca Boldrini/CC BY 2.0)

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Back in the early ’90s, it wasn’t a sure thing that Microsoft Windows was going to take over the market, even though they had a clear lead over many of their competitors, thanks to MS-DOS.

In fact, one of the iconic GUI-based experiences of the era, AOL, hedged its bets for a while, creating and maintaining a DOS version of its iconic pseudo-internet software using a graphical user interface platform few were familiar with: GeoWorks.

It was an operating system for an era when it wasn’t even a sure thing we’d have a modem.

And it was absurdly lightweight, something it gained from its earliest form—as GEOS (Graphical Environment Operating System), an operating system option for the Commodore 64.

The platform, built by Berkeley Softworks—not to be confused with Berkeley Systems, which built the famous “flying toasters” screensaver—was one of the most popular pieces of software on Commodore 64 for a time, thanks to the fact that it was very functional and worked on very inexpensive hardware.

“GEOS did not pioneer the GUI; most of its features were already present in the larger OSes of the day, like the classic Mac (albeit, not Windows),” writer Kroc Camen wrote of GEOS for OS News back in 2006. “What GEOS did show is that cheap, low-power, commodity hardware and simple office productivity software worked. You did not need a $2,000 machine to type a simple letter and print it.”

The operating system eventually moved to the PC in the early ’90s in a more advanced form, and Berkeley Softworks changed its name to GeoWorks.

I had some experience with Commodore 64 thanks to a childhood friend of mine who owned one and let me mess around with it a bit, but ultimately, I caught onto the PC version of GeoWorks because it came bundled with a 386 I used when I was a kid.

That computer wasn’t super-fast—what, with its 40-megabyte hard drive and one megabyte of RAM—and, as a result, it really benefited from the lightweight, object-oriented approach of GeoWorks. The operating system took up maybe 10 of those megabytes, tops. And in an era where connecting to the wider world wasn’t really a big thing, the simplicity of the format was actually kind of nice.

Among the more interesting things about the platform:

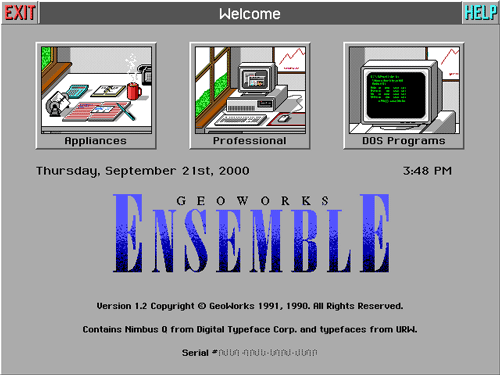

Different interfaces for different skill levels: DOS was not a simple operating system for novices to jump into, and GeoWorks Ensemble made an effort to ensure it was more approachable. It offered two different tiers of usage—“appliances” and “professional,” along with a shell to jump into DOS programs, so you could play Commander Keen without a problem if you really wanted to. For people who had never used a PC before, the strategy was perfect—it had built-in training wheels.

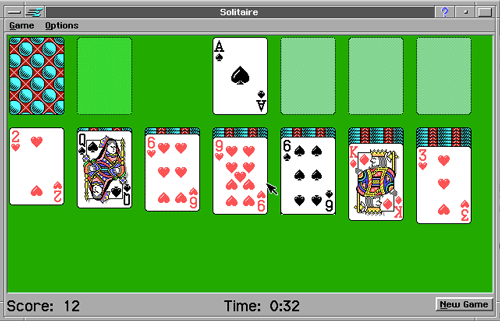

Built-in office tools: The software included a variety of apps that were roughly comparable to anything you could find on other operating systems, such as the Mac including a word processor, calendar, and spreadsheet. It also included a Print Shop Pro-style banner-maker, which came in handy if you owned a dot-matrix printer. Overall, these offerings were great for home users, an audience that Microsoft hadn’t really emphasized early on in Windows’ history. It wasn’t as flashy as, say, Microsoft Bob, but it worked a lot better.

Geoworks’ welcome page. (Photo: Ernie Smith)

Strong capabilities, low power: But the best part of GeoWorks was the fact that it worked well without really strong hardware. Windows 3.1 really needed a 486 to shine, but GeoWorks could effectively run on a 286 or 386 without any problem. It was stable, and despite the fact that (like early versions of Windows) it was essentially a graphical shell for DOS, it rarely ran into hiccups.

The software had a cult fanbase, especially among German computer users, who have done a lot to keep its memory alive.

And Quantum Computer Services, another company that had built early success on the Commodore 64, saw GeoWorks as its opportunity to dive into the PC sphere, launching its first online network for IBM’s PS/1 line of computers.

“The Promenade interface makes it easy for all family members to use the services, without dealing with the frustrations of complicated commands and functions,” Quantum Executive Vice President Steve Case said in a 1990 press release. “Yet the software is advanced enough to satisfy experienced users of online services.”

Within a year, the platform had been reworked into America Online, a company Case famously led throughout the ’90s, and within a decade, the company would be in the middle of an audacious merger with Time Warner—with AOL as one of the defining programs of the Windows era.

GeoWorks had AOL before it was cool—a golden opportunity to take over the home PC market, especially as AOL’s early disks essentially included barebones versions of GeoWorks. That essentially allowed modem owners toget a taste of GeoWorks for free.

But that wasn’t enough. Beyond AOL, GeoWorks had few third-party apps. Part of the reason for this was that, early on, you needed a Sun workstation to develop software for the platform, a deeply ironic requirement—essentially, you needed a $7,000 computer to develop software for low-end PCs, which meant mom-and-pop shops had no chance to even get on board.

At the time, Microsoft was releasing Windows-native development platforms like Visual Basic to win over small developers.

But those limitations could have been dealt with, honestly, if the desktop operating system itself gained a significant audience. Even GeoWorks’ biggest fans knew it didn’t stand a chance against Windows, due to Microsoft’s already-established goodwill.

“I feel badly that this truly amazing program will never be given a chance, as IBM and Microsoft would never allow it,” one such fan wrote to PC Magazine in 1991. “I hope that software developers will see Ensemble’s amazing potential and will begin developing it. Without third-party developers, Ensemble will never survive.”

Microsoft was standing on the shoulders of giants. GeoWorks could barely even reach the ankles.

An old IBM PS/2 with an Intel 386 processor. (Photo: Wolfgang Stief/CC BY 2.0)

But even though GeoWorks failed to win over PC users won over by Windows, the operating system still had a little life in its bones. That’s because, ultimately, operating systems often live multiple lives even if they fail. They show up in random places, because the software is still useful in certain cases.

Palm’s sadly-discarded webOS, for example, currently drives LG’s smart televisions.

GEOS was much the same way. Like a cow shoved through the food manufacturing process and split into a million pieces, parts of GEOS showed up in the ingredient lists of all sorts of weird products. Among the places where GEOS showed its bones:

Personal digital assistants: Before Palm Computing founder Jeff Hawkins came up with the PalmPilot, he formulated an early take on the platform using a stripped-down version of GEOS. The Tandy Zoomer, which came out in 1993, wasn’t a hit, but the collaboration with GeoWorks, Tandy, and Casio proved informative for Hawkins and his team. It helped set the stage for the first truly successful PDA a few years later—one that didn’t use GEOS. (Not to be outdone, Hewlett-Packard created a PDA for the platform itself.)

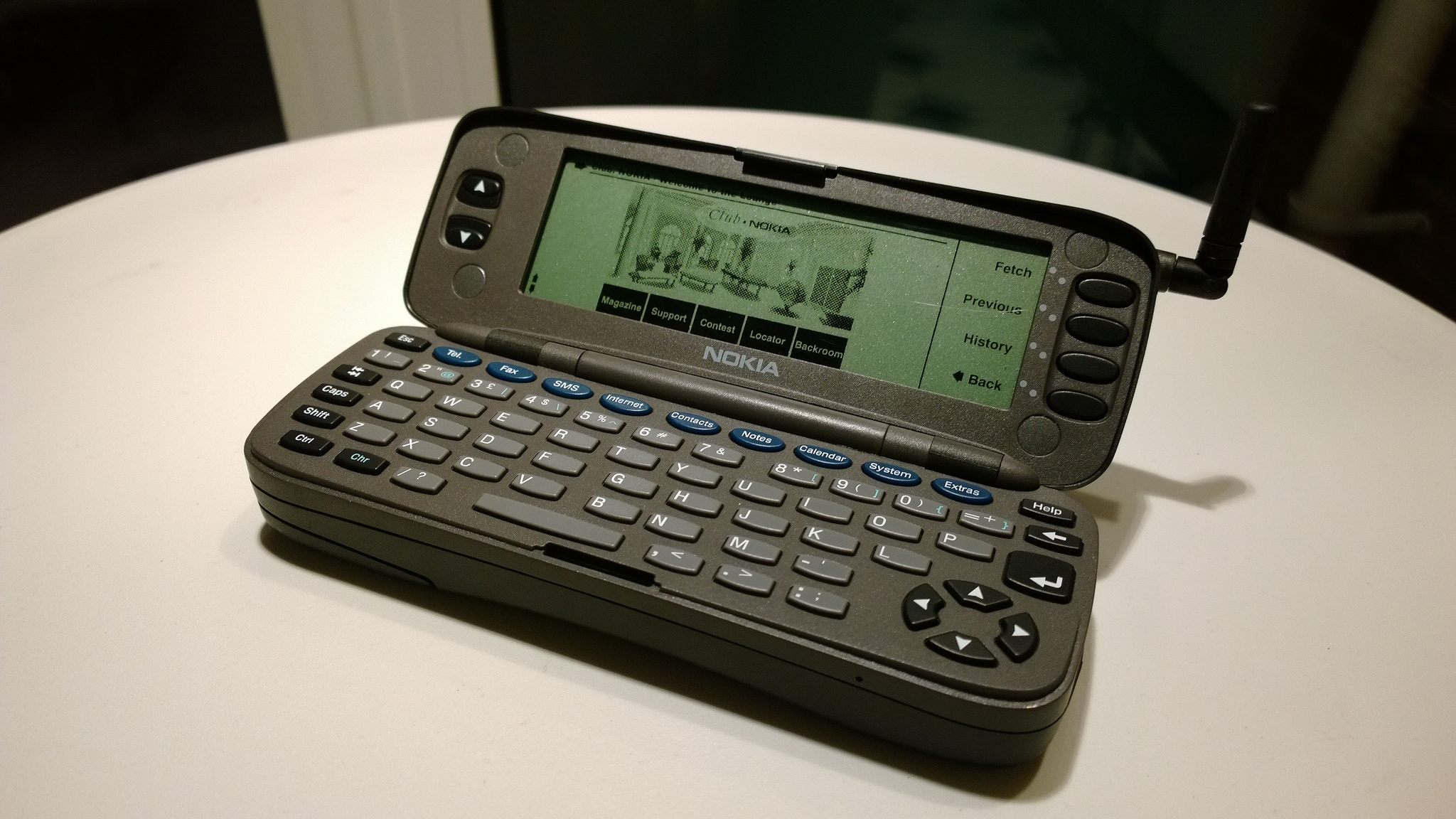

Early smartphones: GEOS’ role in the mobile revolution wasn’t limited to Palm. In the late ’90s, the operating system was a key part of the Nokia 9000 Communicator, one of the earliest smartphones, and one that was well-loved. It was capable of basic word-processing, graphical web-browsing, and could even edit a spreadsheet. For those perks, it wasn’t cheap, costing $800 at launch, and it was Zack Morris huge. “Modern users take features like mobile email and web browsing for granted, but the Nokia 9000 Communicator was the first device to offer these in a single device,” tech writer Richard Baguley wrote on Medium in 2013. “It may have been a bulky, clunky device, but we still miss it.”

A Nokia 9000 Communicator. (Photo: textlad/CC BY 2.0)

Electronic typewriters: The ’90s were a bad time to be a typewriter-maker, and Brother was not well-positioned to handle the internet revolution. But it did have something up its sleeve: GEOS. The company collaborated with GeoWorks on a set of printer variations that added basic word processing and desktop publishing capabilities to the mix. They were still typewriters, but they did slightly more interesting things than write type.

Primitive netbooks: Brother’s interest in GEOS didn’t just extend to typewriters; it saw GEOS as an opportunity to bring “computing to the masses,” as one press release put it. In 1998, years after GEOS had faded from view for just about everyone else, the typewriter company launched an alternative platform—the $500 GeoBook, a low-power laptop that preceded the rise of netbooks by about a decade. It could surf the web and had much of the software available in the DOS version of GeoWorks, but it didn’t have a hard drive, which helped keep the price down. And much like netbooks, reviewers hated them. “For the price of this unit, you can easily find a discontinued, refurbished or used Windows computer and maybe even a new one. It will do hundreds of things that this machine cannot dream of,” a negative 1998 New York Times review explained.

There aren’t any crazy GEOS projects like this nowadays that I’m aware of, but hey, maybe it’s running an ATM somewhere.

Despite the number of extra lives GeoWorks has had, the outlook of the platform looks more dire than ever in 2016.

This is partly due to the complicated corporate history around GEOS. After the company that created the software dissolved in the late ’90s, the technology was sold off to a firm named NewDeal, which built an office suite out of GEOS, one that looked a lot like Windows 95 and took away a lot of the platform’s unique charm.

At one point, the operating system was owned by Ted Turner’s son, who attempted to run a low-cost PC company called MyTurn.com, with the GeoWorks software as its centerpiece. (When Teddy Turner ran for Congress in 2013, his MyTurn.com days came back to haunt him.)

Eventually, the operating system ended in the hands of a company called Breadbox, which had essentially treated GeoWorks as a volunteer upkeep project, with the eventual goal of turning the GEOS into an educational software platform that worked in tandem with Android.

But recently, Breadbox went into hibernation. In November, founder Frank S. Fischer died unexpectedly as they were in the midst of creating a version of the software for tablets.

John F. Howard, his longtime partner on Breadbox, is currently working on next steps, talking things over with Fischer’s family as well as other developers who are interested in the platform.

“There are still some legal issues to resolve, but I am confident that there is still some life in the GEOS code,” he wrote on the Breadbox website last month.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook