The Insouciant Heiress Who Became the First Western Woman to Enter Palmyra

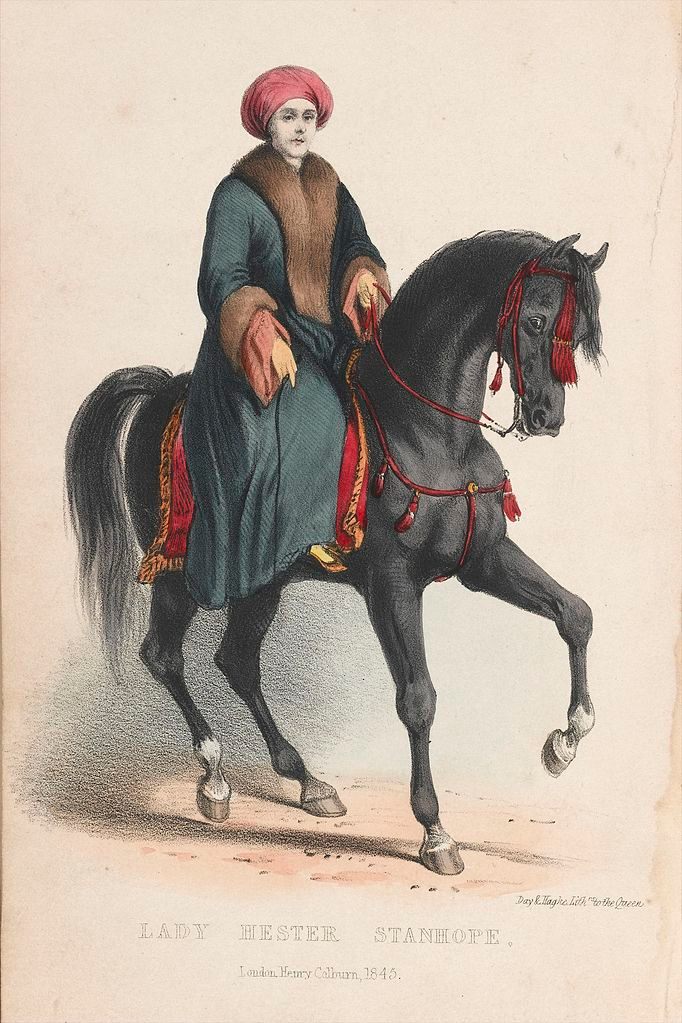

Lady Hester Stanhope on horseback. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London/WikiCommons)

Born to an aristocratic family in 1776, a young Hester Stanhope was passed from her eccentric father to her grandmother who, not knowing how to deal with the rebellious child, handed her off to her uncle. That uncle just happened to be British prime minister William Pitt the Younger, who led the country during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars after taking office at 24.

After arriving at number 10 Downing Street, Stanhope became a smart young hostess for her bachelor uncle, charming his many important visitors with her wit and intelligence. Later on, she nursed Pitt when he fell ill from ulcers and gout. When the prime minister died, in 1806, he left his niece a generous pension of £1,200 a year to live on.

Stanhope’s inheritance allowed for a comfortable life in England, but it wasn’t enough to partake in the endless socializing expected among her social circle. Aged 33 and despondent after a thwarted love affair that scandalized London society, Stanhope took her inheritance and headed east, writes Lorna Gibb in Lady Hester: Queen of the East. She would never again set foot in England.

With a maid and a young doctor, Charles Meryon, as chaperones, the party’s itinerary was constricted to the regions where Napoleon was not engaged in battle. First stop: Gibraltar. Here she met a young, flamboyant group of men that included a handsome 21-year-old, Michael Bruce, and the celebrated romantic poet Lord Byron–who disparaged Stanhope as “that dangerous thing–a female wit.” Bruce became Stanhope’s lover, and they sailed together from Gibraltar to Athens, Constantinople, and from there intended to go to Cairo.

Lady Hester Stanhope dressed in men’s clothes after a shipwreck on Rhodes. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Shipwrecked on Rhodes en route, the whole party lost their belongings at sea and had to buy new clothing, thus adopting male Ottoman dress. When they finally landed in Cairo, Stanhope embellished her outfit further, cinching the waist of her embroidered pantaloons with a jeweled Albanian dagger, shaving her hair to better fit inside a cashmere turban, and wearing a colorful sash replete with pistols and a saber.

From then on, Stanhope wore Eastern male dress for the rest of her life. It was a look that, together with her inordinate charisma, saw her mistaken for royalty wherever she went. Researcher Avi Sasson writes, “At first, Arab leaders saw their meetings with her as strange, but she quickly swept them away. There’s a drawing that shows her sitting with a sheikh in Lebanon, and they’re smoking a hookah together. Women didn’t smoke back then, certainly not in public.”

Warned in a letter from the pasha of Damascus to wear a veil when visiting the devout Syrian capital–or risk facing an angry mob–Stanhope paid no heed and rode through the city gates in full male attire. The crowds, at first stunned, started to cheer, paying their respects by scattering coffee grounds in her wake. It seemed that Stanhope was so out of the ordinary that people couldn’t help but be delighted by her, and what could have earned another woman a lashing saw her revered.

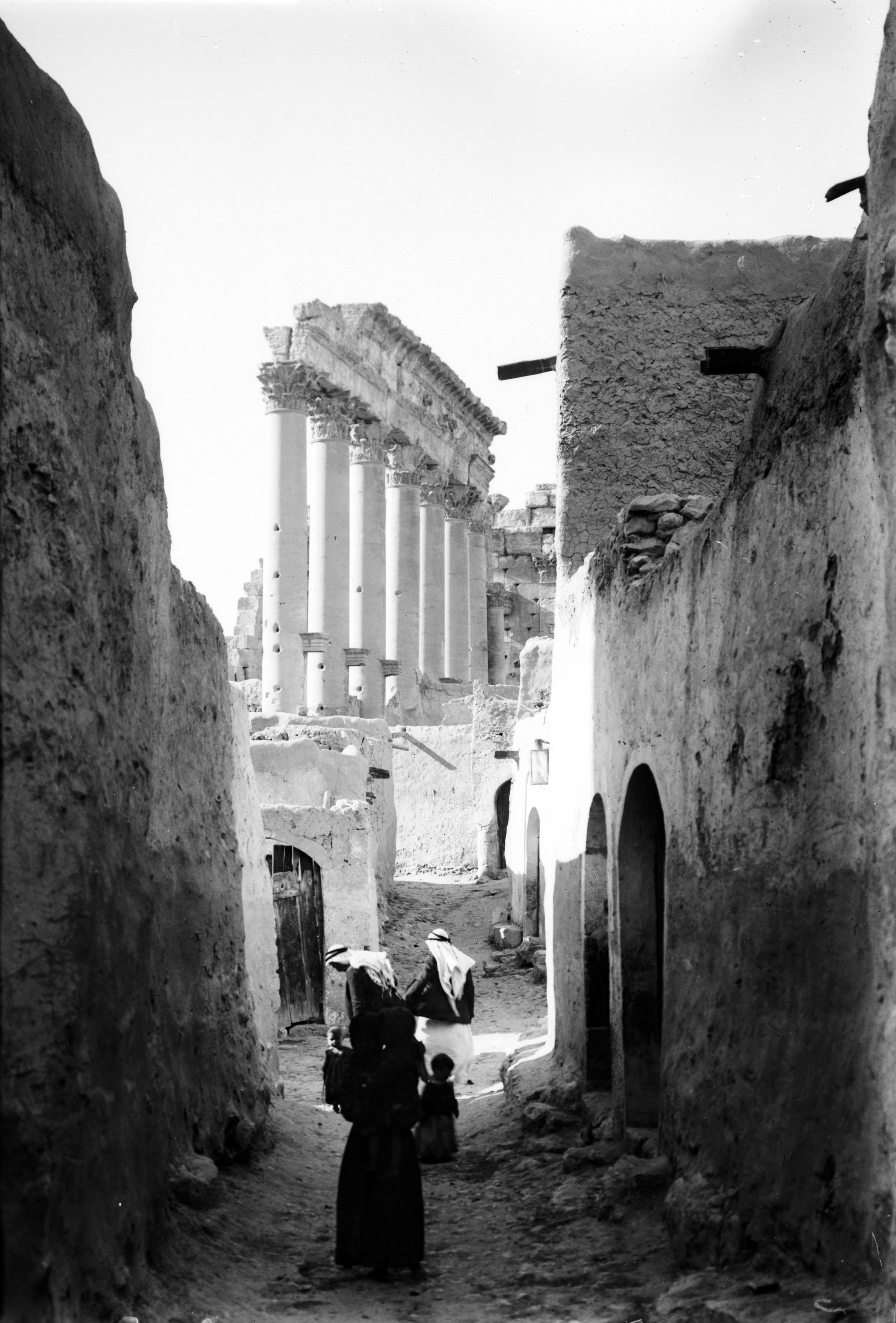

A village within Palmyra’s Temple of Bel, during the early 20th century. (Photo: Matson Collection, Library of Congress/Public Domain)

Once in Syria, Stanhope set her sights on visiting the ancient capital of the Syrian desert–Palmyra. The lure of being the first European woman to reach the ruins intoxicated her, and she wrote, “If I had been a man, my love for fame would have been unbounded.”

The journey was not easy or cheap; it involved a week’s riding through a desert wasteland controlled by Bedouin tribes. Many other travelers had tried and failed. For a hefty fee, though, Stanhope managed to negotiate the safe passage of her party with Muhana Al Fadil, chief of the Hasanah tribe. Now accompanied by 70 Bedouins carrying long lances plumed with ostrich feathers, Stanhope, Meyron, and Bruce headed out to the rose-gold city on horseback.

The Bedouin guides gave the insouciant heiress a moniker she increasingly believed: “I have been crowned Queen of the Desert… I have nothing to fear… I am the sun, the stars, the pearl, the lion, the light from heaven,” she wrote.

Legend has it that Stanhope was welcomed to the ancient Silk Road city by a crowd of young women singing and dancing, who presented her with a flower crown at Palmyra’s iconic Arch of Triumph (a 2,000-year-old treasure sadly destroyed by ISIS in 2015).

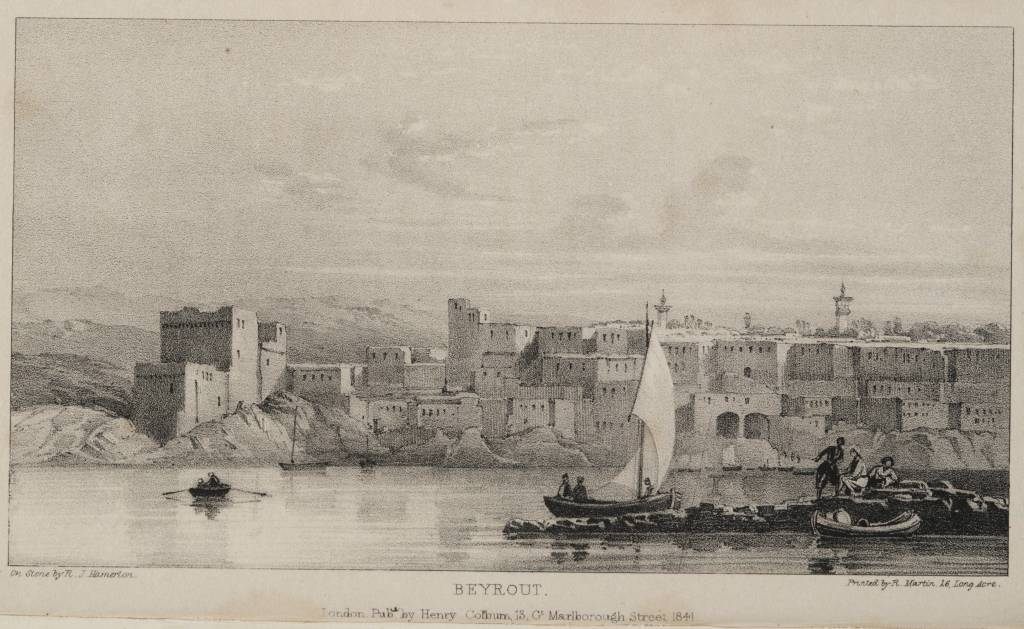

An 1841 illustration of Beirut. (Photo: TIMEA/CC BY 2.5)

After the excitement from her trip to Palmyra had worn off, Stanhope decided to look for lost antiquities herself. Biographer Lorna Gibb tells the story of how, in 1814, Stanhope had been shown a medieval Italian document that told of a great treasure–three million gold coins–buried at the ancient city of Ashkelon (in modern-day Israel). A year later she’d secured funding from the British authorities and permission from the Ottomans to conduct the first modern archaeological dig in the Holy Land.

However, two weeks of digging with a full team unearthed only a seven-foot-tall marble statue of a headless Roman warrior. Stanhope ordered that it be “smashed into a thousand pieces” and scattered across the site. But this wasn’t the senseless and devastating act of pettiness that it appears–she did so to prove she wasn’t planning to spirit any antiquities away (this was only a decade after the Parthenon Marbles had been stolen from Athens by the Earl of Elgin), and her seemingly rash action apparently paved the way for more Western archaeologists to dig there.

For many of her journeys, Stanhope’s companion had been Michael Bruce, the aristocrat 12 years her junior whom she’d met in Gibraltar with Lord Byron. But other expatriates had been spreading the scandal of the pair’s age gap, and her quixotic dress and behavior, back to England for years. Bruce’s embarrassed father, Crauford, was constantly threatening to cut his son off. When Crauford became seriously ill, Bruce decided it was time to sail home to make amends. He didn’t stay faithful to Stanhope, though, and the more women he got entangled with on the journey back to England, the more he ignored Stanhope’s fraught love letters.

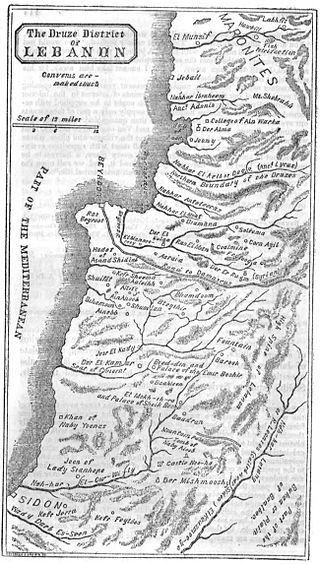

An 1844 map of Lebanon, showing Lady Stanhope’s residence on the bottom left corner. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

An 1844 map of Lebanon, showing Lady Stanhope’s residence on the bottom left corner. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Stanhope was distraught and increasingly flew into rages at her servants at the small monastery she had decided to rent in the foothills of Mount Lebanon. Without Bruce’s large allowance to embellish her own pension, she was now living under greatly reduced circumstances. However, this didn’t stop her from acting like a “medieval monarch” when the area was caught up in a civil war in the mid-1820s, and taking in “every peasant, friend and stranger who came to her door,” including hundreds of Druze refugees who she fed, clothed, and gave shelter to. And when sheikhs and princes visited, she’d gift cash and clothes she could ill afford.

Although she continued to write letters and receive visitors, Stanhope entirely ceased leaving her monastery home, and became a recluse for the last years of her life. Withdrawing into the realm of the spirits, smoking hookah all day and night, and barely sleeping or eating, Stanhope died in 1839, aged 63, heavily in debt yet attended by 37 servants.

Hester Stanhope’s biographer, Joan Haslip, sums her up best, “She was neither a man nor woman, but a being apart.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook