The Mystical Early Pennsylvania Settler Who Lived in a Cave

Johannes Kelpius was really keen on the apocalypse.

Wissahickon Creek, Pennsylvania. Johannes Kelpius’ cave was located near Wissahickon. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ppmsca-24881)

In the mid-17th century a religious mystic, seeker, and occultist named Johannes Kelpius laid in his bed in Transylvania, and he dreamt of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. And so, he went.

Today in the neighborhood of Germantown, a few miles north of Center City, you can see where Kelpius would eventually live and die. By the Wissahickon Creek in Fairmont Park you can enter the cave that the largely forgotten Kelpius called his home.

It’s an unlikely spot to await the apocalypse, but religious fanaticism is not a new creation. Here, amongst broken beer bottles and graffiti, is what was once the anchorite’s cell where Kelpius and his band of mystical-minded, radical Protestant “monks” studied the Christian kabbalah, astrology, and magic. They awaited the apocalypse that they believed Revelation had foretold as beginning in this new city in a New World, on the western edge of everything, and east of Judgment Day. And while they waited that date (a 1694 which came and went without the end of the world) they prayed, they divinated, they meditated, they wrote, and they supposedly discovered occult secrets here by the shores of the Schuylkill.

For John Greenleaf Whittier, the Fireside Poet of the 19th century, Kelpius was “weird as a wizard” with command “over arts forbid.” In a province where the second book printed after the Bible was a volume of occult lore, Kelpius was still one of the “maddest of goodmen,” as Whittier put it.

Johannes Kelpius. (Photo: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania/Public Domain)

He was born in 1667, only one year after a diabolically and auspiciously apocalyptic year, which saw widespread millennial excitement throughout Europe. He was raised amongst the German minority of Transylvania, then an independent kingdom known for both its religious freedom and heterodoxy (as indeed Kelpius’ future home of Pennsylvania would be as well). Perhaps Kelpius would come to see something similar to that which he learned in his upbringing, among the wilderness of America.

While still in Europe, Kelpius read the works of the Pietist Jakob Böhme, who was also a firm believer in the coming apocalypse. Based on both his reading of Revelation which spoke of an exilic remnant of the faithful that was as a “woman in the wilderness,” as well as glowing accounts of the colony of Pennsylvania, Kelpius became convinced that the “Philadelphia” which John of Patmos wrote of was not the historical settlement in Asia Minor, but rather this new metropolis on the American frontier. At the time, this proprietary English colony was the largest private land holding on Earth; it was also marked by an exceptional ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity, truly a remnant of the varied faithful in this wilderness.

Welcomed by that similarly religious non-conformist Penn (even though Kelpius’ private diaries could be scathing to the point of ingratitude when discussing the Quaker), Kelpius would make his home among the growing German population around Philadelphia, such as Daniel Falckner who was advocate for the colony in his pamphlet Curieuse Nachrischt von Pensylvania, and the brilliant polymath Daniel Pastorius who functioned as the de facto leader of the German community. Yet Kelpius and his fellow pilgrims were as men apart from Pennsylvania German society, true to the principles living in the wilderness of the forest with natural caves as their cells, awaiting the end of the world.

The entrance to Kelpius’ cave. (Photo: Justin 0 of 0/CC BY 2.0)

While he and his followers lived in their monastic cells, here in what would be Germantown, Kelpius composed some of the first German hymns to be written in the New World, he trained his followers in the divine numerology of gemetria, and the community supported itself by casting astrological charts for the immigrants of Philadelphia. In this, his “Society of the Women in the Wilderness” attempted to create a perfect, communcal society—a utopia which would be present to witness the apocalypse.

Kelpius may have viewed himself as a prophet, but he was no founder of a new faith. Idiosyncratic though he may have been, he viewed himself as within the main currents of Protestant thought. The world did not end in 1694 as he predicted, but in many ways it did die with his death in 1708. His followers, always small in number, were largely dispersed with the magus’ passing. Whether the prophet died in his cave or not is unknown.

But, as a bit of local lore has it, that alchemist discovered the mythic “Philosopher’s Stone” capable of transmuting base metals into gold, only to toss it into the river before he died—even though some followers claimed that Kelpius never really did expire, rather elevating to a higher realm like the biblical prophet Enoch.

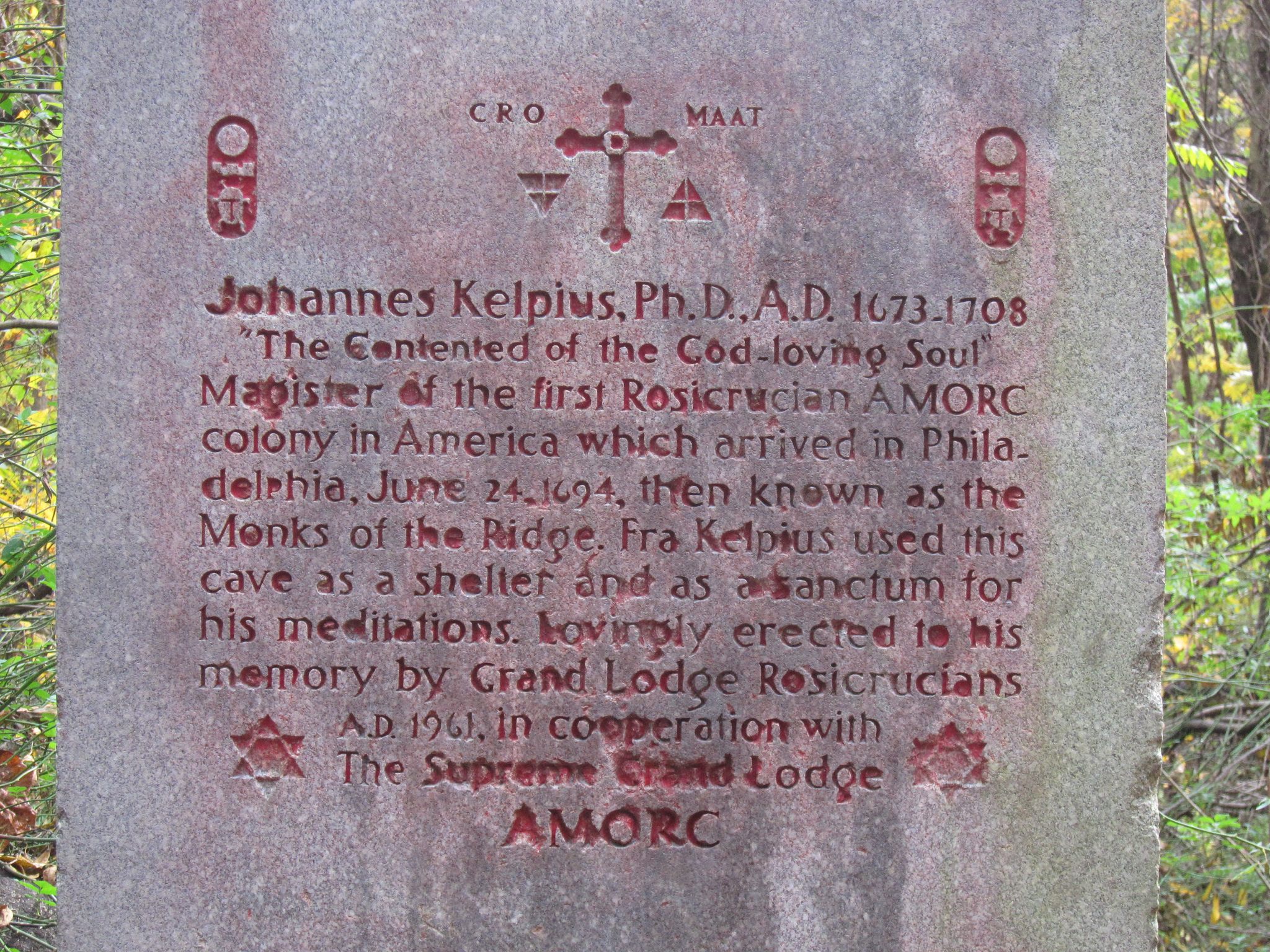

A plaque commemorating Kelpius’ cave. (Photo: loppear/CC BY 2.0)

The utopian religious freedom promised by Pennsylvania would attract other pilgrims, like the Amish, the Mennonites, and the Moravians in the 18th century. The 19th century would see a young Joseph Smith believing that he had restored the Aaronic line upon the Susquehanna River, as well as other attempts to build a perfect society such as those at New Harmony and Ephrata, the later of which was directly influenced by the example of Kelpius. And the 20th century would see the arrival of the utopian Bruderhof as refugees from Hitler’s Germany. Over more than three centuries the state has been a haven for the searchers, the seekers, the eccentric, the dreamers, the divinators; Kelpius was simply an early one. Kelpius may have hoped for a Peaceable Kingdom in the wilderness, though paradise did not descend his prophesized year. That is not justification for turning one’s face away from Eden (or Philadelphia). You may yet see the gentle glow of the Philosopher’s Stone at the bottom of the Schuylkill River.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook