The Pagan Approach to #Blacklivesmatter Involves Carefully Crafted Hexes

At the annual PantheaCon gathering, pagans addressed modern social injustices with ancient witchcraft.

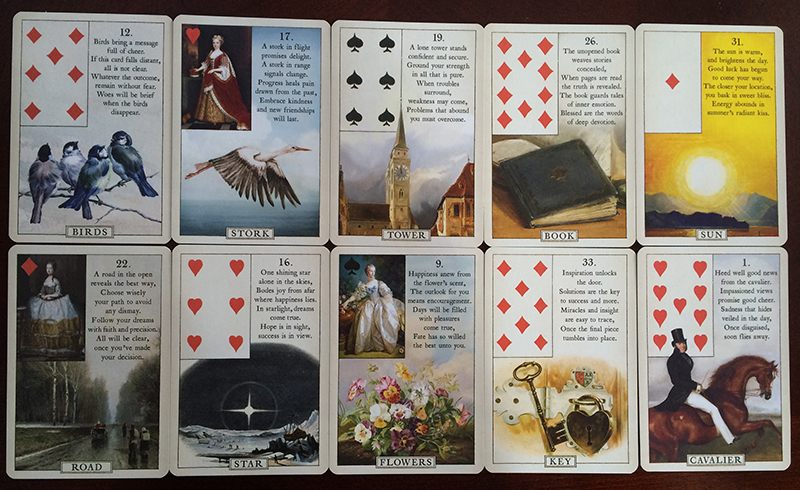

Lenormand Fortune Telling Cards at PantheaCon. (Photo: Tarin Towers)

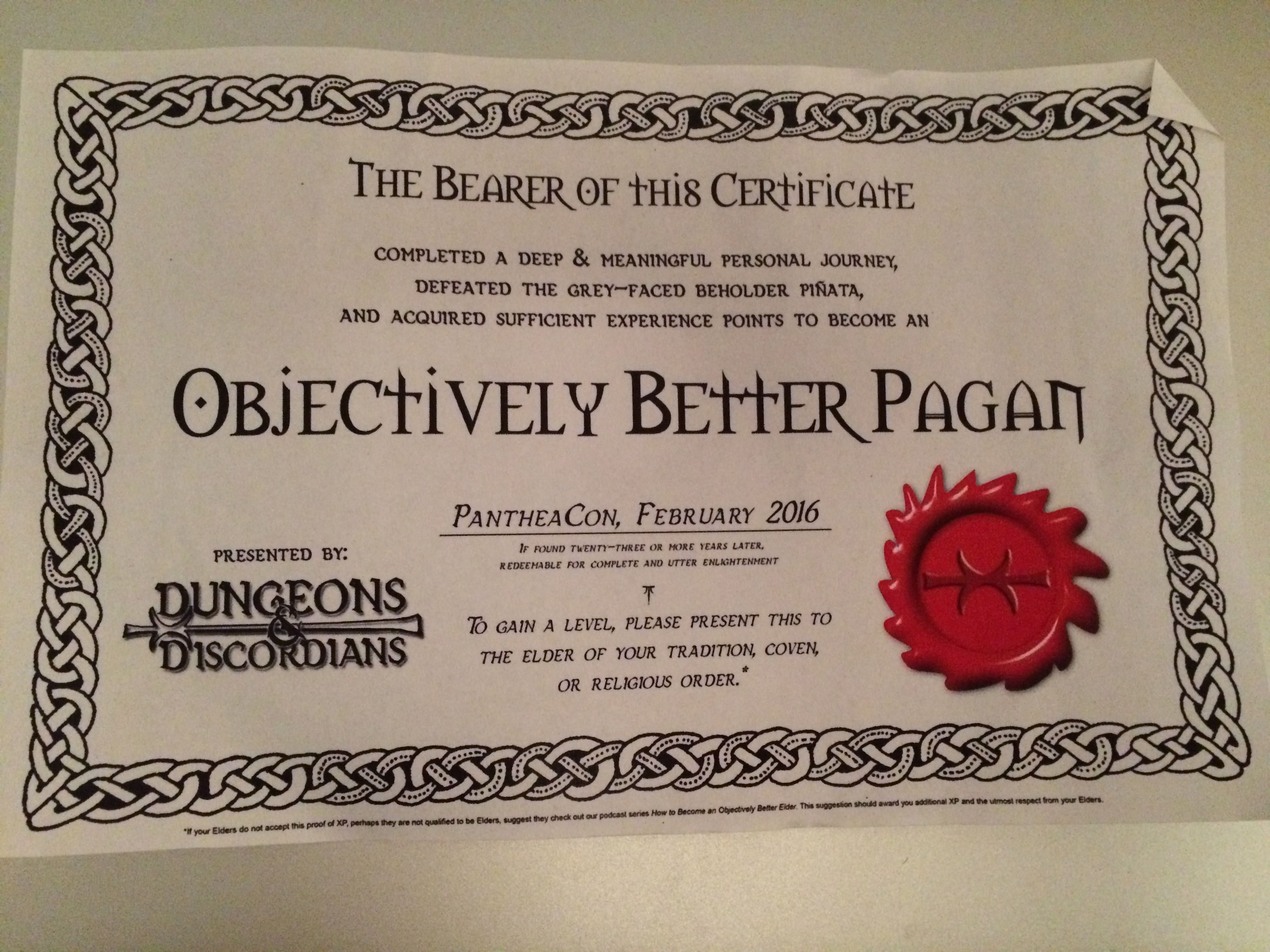

“Are we LARPing now, Daddy?” asked a little girl of about eight, wearing fairy wings and a crown. Surrounding her in the San Jose Doubletree ballroom at 11 p.m. on a Friday night were about 75 people sitting at long tables rolling dice. They were preparing for a ritual. If they defeated the ancient evil, disguised as piñatas full of candy and paperwork, they would be declared “Objectively Better Pagans” and receive an official certificate.

One might be tempted to look around at this collection of worshippers of chaos (Hail, Eris, goddess of discord!) assembled for the “Dungeons and Discordians: Vault of the Greyface” ritual at PantheaCon 2016 and assume they were gathered together to playact paganism. But making assumptions about anyone’s beliefs—or lack thereof—would be a mistake here.

A certificate for becoming an ‘Objectively Better Pagan’. (Photo: Tarin Towers)

February’s 22nd annual PantheaCon, a pan-pagan gathering in Northern California, drew an estimated 3,000 Witches, Druids, Heathens, healers, historians, high priestesses, reconstructionists, magicians, and members of other far-flung, earth-based traditions. Not everyone at PantheaCon opts for silliness as a spiritual practice, but all attendees—people of myriad faiths, genders, backgrounds, and abilities—came to the conference rooms at the Doubletree seeking mysteries and wonder.

This year’s program featured 223 public presentations: rituals, lectures, concerts, panel discussions, and demonstrations of craft—both handicraft and spellwork. A Sunday could begin with singing “the Morning Hymn used to waken the Gods and Goddesses in Egyptian Temples” followed by a lecture on Exorcism in the Ancient World. After lunch, there was Magick Incense Making with Lavender, followed by a Druid rain ritual involving drumming to “open the Gates to the Otherworld” and alleviate the crushing California drought.

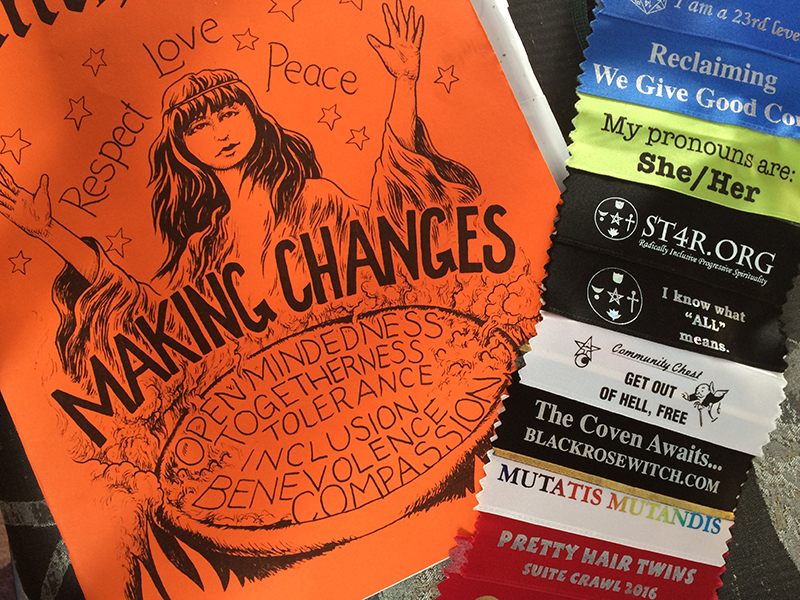

The theme of PantheaCon 2016 was “Making Changes,” and the program’s pumpkin-orange cover featured a witch presiding over a cauldron, in which bubbled words like Open-mindedness and Inclusion. PantheaCon has served as a social cauldron for many years—not a melting pot but rather an alchemical vessel where things stew together until transformations occur, sometimes slowly and temperately and sometimes with sudden sparks.

A close-up of the PantheaCon Program and Badges. (Photo: Tarin Towers)

A few years ago, gender justice came to the forefront when a ritual held by a pagan elder excluded women who were not “born women.” This year’s con offered attendees lots of opportunities to honor gender’s own pantheon, including badge ribbons indicating preferred pronouns. One older woman asked the information desk why someone who looked like a man would bother wearing a ribbon that said “He/Him.” “That’s not very exciting,” she said. “Most people aren’t telling you their gender because it’s interesting,” the volunteer replied. “It’s because they’d rather talk about other things.”

Social justice themes were woven through the programming, not just on panels like “Radical Inclusivity” but in magical workings focused on anti-racism. Black Lives Matter activists facilitated powerful healing rituals, while on another—but not separable—axis of the larger pagan community, Heathens discussed a continuing rift in their community around some organizations’ exclusion of nonwhite members and embracing of far-right politics.

Brigid Altar in the Reclaiming Hospitality Suite. (Photo: Irisanya Moon)

One presentation, “Willful Bane: The History, Techniques and Ethics of Hexing,” was hosted by Byron Ballard, village witch of Asheville, North Carolina. She describes herself as a practitioner of Shenandoah Valley folk magic, which blends traditions from the British Isles with those of both the Cherokee and the Amish. Witches are taught something called the Rule of Three, which recommends against hexing—as Ballard defines it, casting spells that curtail another’s free will—because ill intent in the spell can bounce back on the one who cast it, three times.

“The Rule of Three doesn’t work,” says Ballard. Hexing, she said, works for oppressed people, those marginalized outside legal paths to justice. In situations like these, where calling the police may not be the best option, bane work is performed “with a clear head and an open heart,” allowing people to “hex without it bouncing back on you.” Ballard demonstrated spells that would diminish another’s power using folk materials—that is, things you might have on hand—like Mason jars, marshmallows, and twine.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook