A Sleep Researcher’s Attempt to Build a Bank for Dreams

John Henry Fuseli’s famous painting ‘The Nightmare’, from 1781. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

For many people, listening to just one person describe their dreams is a nightmare. But for G. William Domhoff, it’s a calling; as a dream researcher, he listens to them professionally.

But even a dream doctor has his limits.

“As soon as people find out what I do, they want me to interpret their dream,” says Domhoff, a research professor in psychology and sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz and author of several books on dreams.

But dreams are a numbers game and Domhoff prefers to work with big data sets, not a single offering. Over the years he has collected and analyzed a vast library of dreams and is one of the founders of The DreamBank, an online archive of over 22,000 dreams. The database, which is available for the public to sift through, is an attempt to quantify one of the most ephemeral of human experiences.

Dream research really took off in the 1950s when rapid eye movement sleep, or REM sleep, was identified and connected to dreaming. Scientists once thought dreaming only occurred during REM; now it is believed it can happen at other times, too. (Domhoff is currently working on a book exploring the connection between “mind-wandering”—or daydreaming—and dreams.) This jumpstarted laboratory research in which sleeping subjects were awakened and asked to describe their dreams. Laboratory research remains a common way to collect dreams, along with asking students and other groups to record their dreams in diaries. But collecting dream data is inherently challenging.

“You can’t make them happen,” says Domhoff.

And assigned dream journals carry their own risks.

“We’re always at the mercy of the participant whether they’re telling us accurately or not, whether they’re embellishing,” says Domhoff. For instance, a bashful subject may omit an amorous dream.

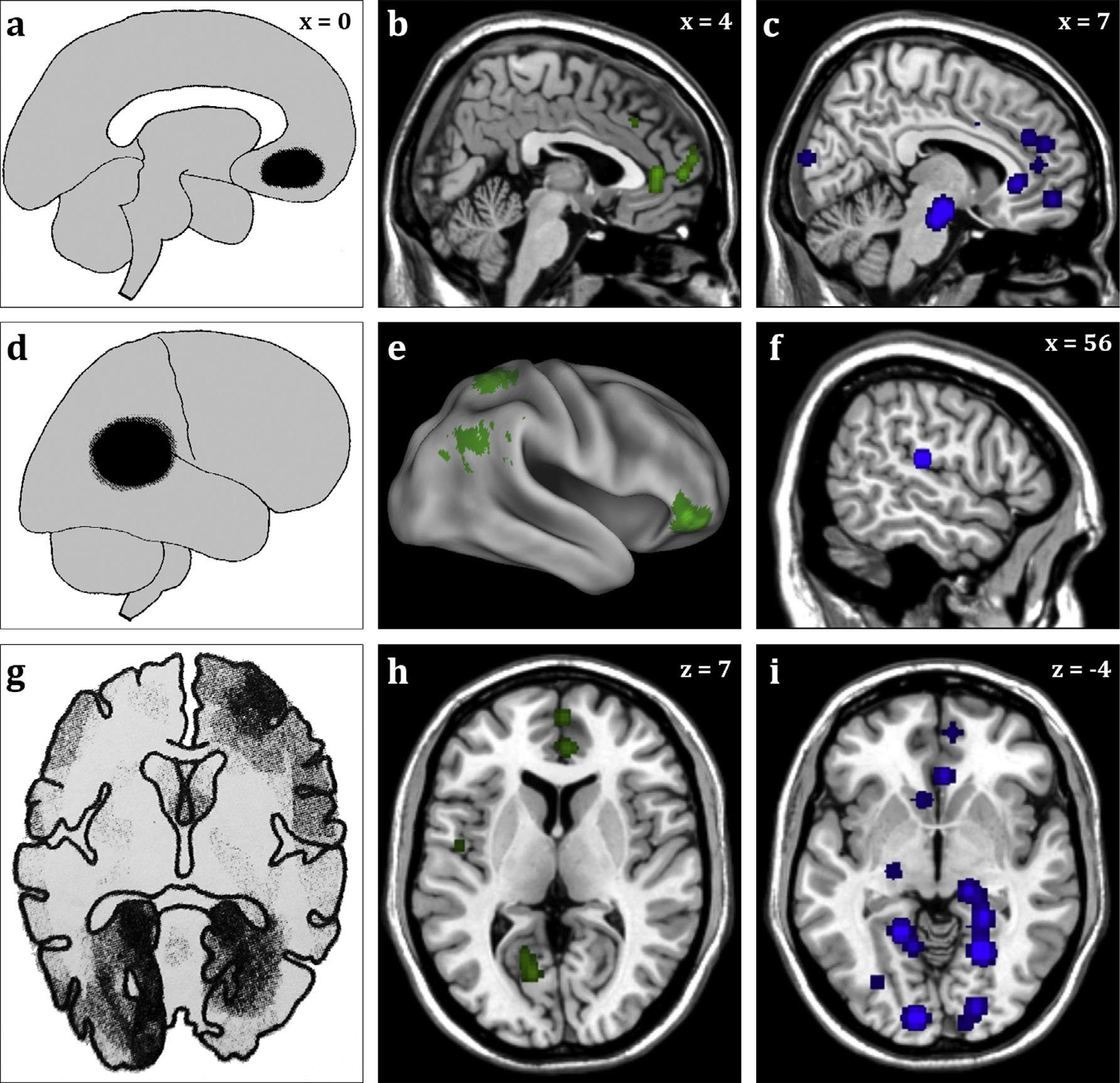

Brain activations shown in a recent paper on Dreamresearch.net, during dreaming (left column), waking daydreaming (middle) and REM sleep, which is nearly always accompanied by dreaming (right). (Photo: G. William Domhoff/dreamresearch.net)

So what’s a dream researcher to do? Seek out dream records maintained by people for what Domhoff terms “their own reasons.” And many of the dreams deposited in The DreamBank are such documents.

There’s the diary of a widower who began writing down every dream he ever had about his deceased wife. (Domhoff devoted an entire paper to this diary.) The database holds 3,116 dreams from a woman who has been recording them since 1977. Another dreamer, “Dorothea,” contributed 900 dreams recorded over 53 years, starting in 1912.

The bank has its roots in records Domhoff inherited from his mentor, Calvin S. Hall, a psychologist who created a coding system for dreams that allows researchers to track things like recurring characters, activities and objects. Hall died in 1985 and his collection remained inaccessible to most. In 1999, Adam Schneider, a student of Domhoff’s, suggested that they could put the texts online and make them searchable. The DreamBank was born and current collections were added to Hall’s historical ones.

Prof. G. William Domhoff in conversation with psychologist Calvin S. Hall at the University of California in 1968. (Photo: Courtesy Special Collections/ University Library/ UC Santa Cruz)

Prof. G. William Domhoff in conversation with psychologist Calvin S. Hall at the University of California in 1968. (Photo: Courtesy Special Collections/ University Library/ UC Santa Cruz)

The archive is organized in 73 dream sets. Most of those sets are dreams collected from an individual, but some are from groups who were assigned to keep diaries, such as blind dreamers and Swiss schoolchildren. Over the years, people have heard about The DreamBank and submitted their privately kept journals to be preserved and made available to readers. Domhoff believes in granting anonymity to dreamers, and many of the pseudonyms in The DreamBank are both colorful and descriptive such as “Pegasus: the factory worker” and “Toby: a friendly party animal”.

Since the bank went online, several researchers have used the data to conduct studies into dreams. And the current iteration might only be the start: Domhoff believes today’s smartphone technology may be the key to amassing even more dream data, and he’s not the only one. In 2014, Hunter Lee Soik, a former freelance creative director, crowdsourced $82,500 to build an app that people could use to record their dreams and then send them to a database for coding. Just like Domhoff, Soik hopes that giving researchers access to data will help them better understand dreaming.

So what is it like to read through the bank? In a sense it’s like being a room full of people who are telling you their dreams. The narratives are simultaneously strange, dull and absorbing.

Toby, for instance, often dreams of attractive women and smoking weed:

All the sudden we’ve stopped to get dinner and then all the sudden I’m at the front of the line looking at the cashier. She’s a redhead with straight hair and a really hot face and straight, perfect white teeth. I look up at the menu and recognize it as Jack-in-the-Box. For some reason I’m confused and am having a hard time ordering. She notices and I look up at her and say, “I’m not having a hard time ordering because I’m high, okay,” and she looks at me sexually and says, “That’s okay, take your time.”

The dreams are searchable by keyword. Here’s a dream about 12-year-old “West Coast Girl” had about a cat:

I saw a light outside and I saw a UFO. Out came ET and he points his middle finger at me and said “phone home.” My sister came out with my cat and screamed. ET took my sister and I was very happy. Then he took my cat and I was mad so I threw a huge rock at ET and ET disappeared. Then it was the morning and my sister and my cat were home so I went to Safeway at about 2:00 and I saw Billy Joe Armstrong [sic]. I asked him for his autograph but he ran away. His parents were there.

Famous people make cameos: Candice Bergen, Kiefer Sutherland, Bill Murray. Ed, the widower who recorded only dreams of his deceased wife Mary, dreams that she and Jerry Seinfeld abandon him while on an outing: “I am bored because I have nothing to do, and angry at Mary and Jerry for deserting me.”

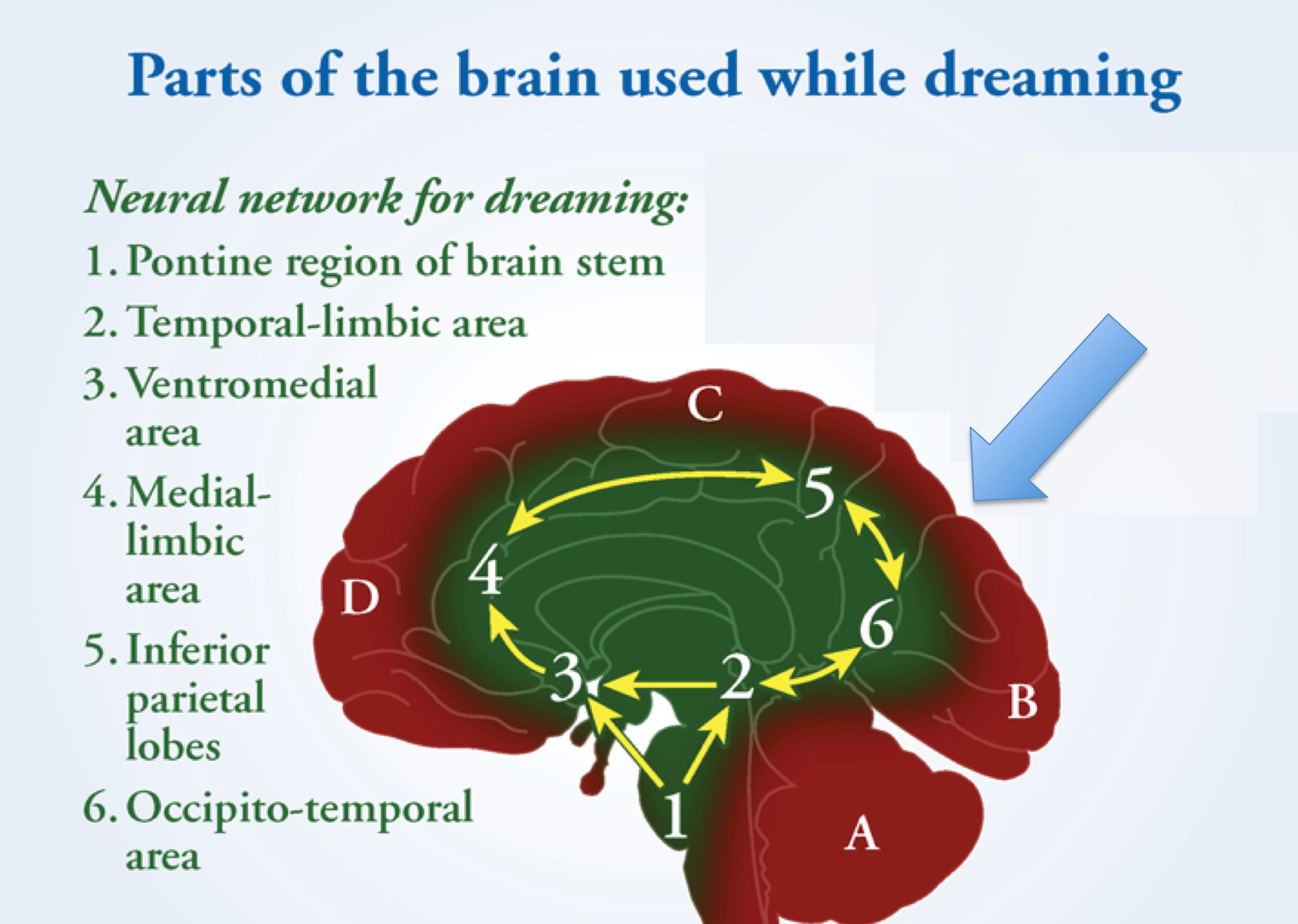

A Chart of the neural network for dreaming, which is still being refined and researched. (Photo: G. William Domhoff)

A Chart of the neural network for dreaming, which is still being refined and researched. (Photo: G. William Domhoff)

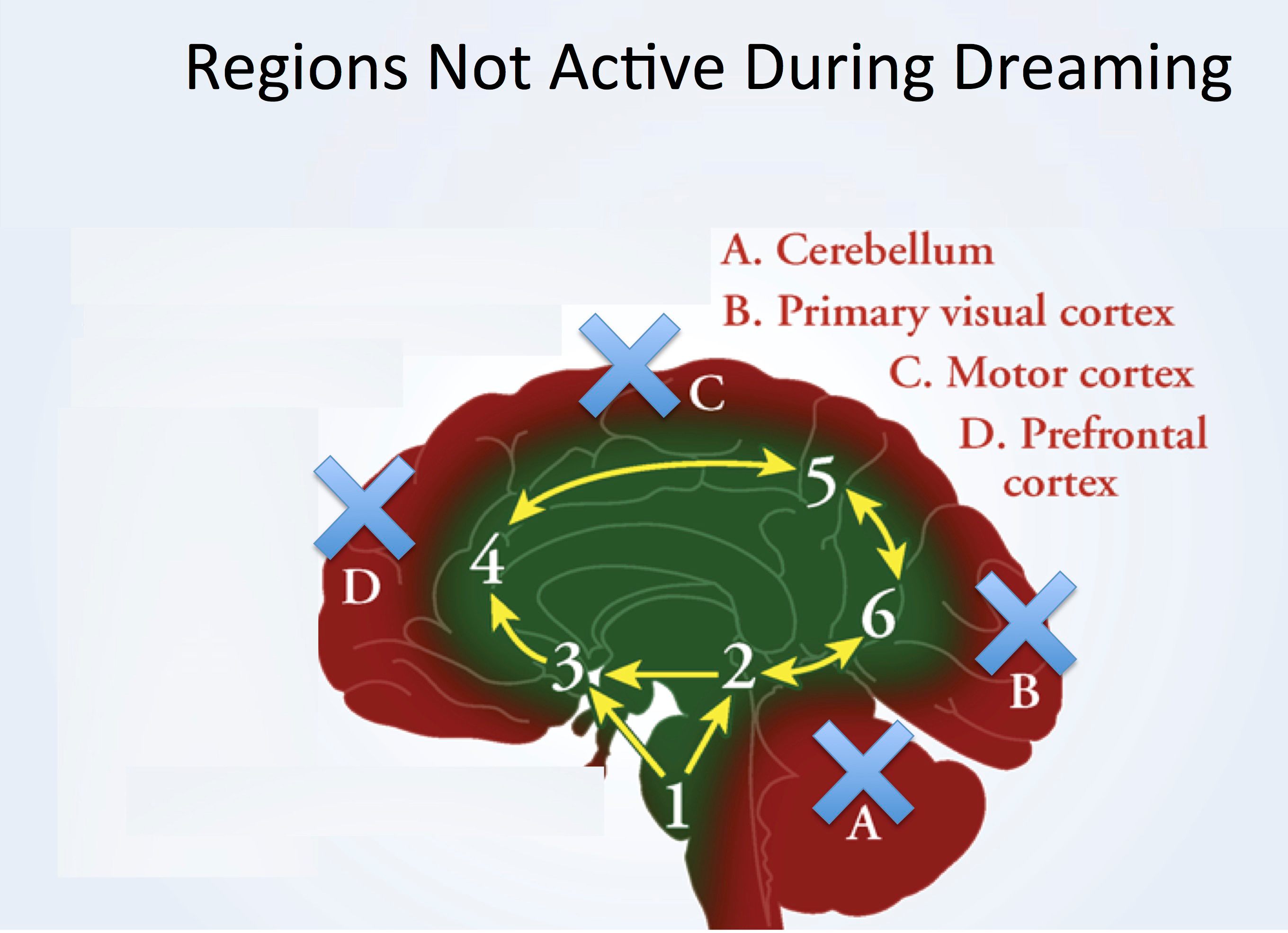

Areas of the brain that are believed to not be active during dreaming. This is, as Domhoff says, a “first draft” of scientific research. (Photo: G. William Domhoff)

So, after combing through decades of data, can Domhoff interpret our dreams? Well, yes and no.

First of all, Domhoff understands the urge to assign meaning to dreams.

“Dreams are so real,” he says. “Uncle Frank is sick or Nancy slapped Betty, we want to make sense of them. We can’t see it as random.”

But there’s a lot of “noise” in dreams, says Domhoff. In order to even begin parsing the meaning of a person’s dreams, Domhoff would need lots of dreams from that person—not just a single, memorable one. And, while many cultures have ascribed fantastic possibilities to dreams from diagnosing illness to predicting the future, Domhoff’s assessment is a bit more sober. Dreams, he says, are an expression of the same thoughts and concerns expressed in our waking life.

“If you never got over Joe, you’re still bitter, angry or still love him dearly then Joe’s going to keep popping up,” says Domhoff.

In other words, you aren’t the only one dreaming about work. As for Domhoff, it’s hard to say what he’s dreaming about. The researcher doesn’t remember most of his own dreams.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook