The Story Behind Gay Bob, the World’s First Out-And-Proud Doll

He debuted in the ’70s, to both acclaim and outrage.

“It’s another evidence of the desperation the homosexual campaign has reached in its effort to put homosexual lifestyle, which is a deathstyle, across to the American people.”

A lobby group called Protect America’s Children made this statement in 1978—about a doll.

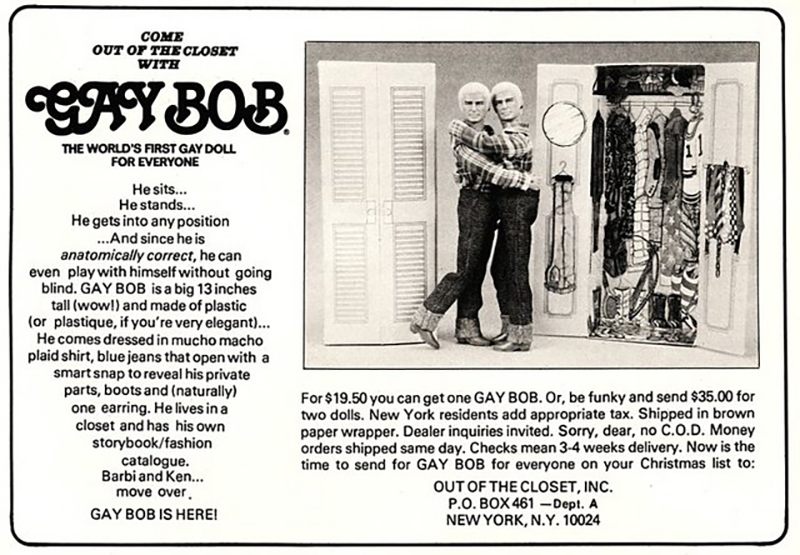

That year, the release of Gay Bob, billed as the world’s first openly gay doll, caused a minor sensation. Enraged consumers complained that a toy with a homosexual backstory would lead to other ”disgusting” dolls like “Priscilla the Prostitute” and “Danny the Dope Pusher.” Esquire awarded Gay Bob its “Dubious Achievement Award.” And anti-gay organizations across the United States blustered.

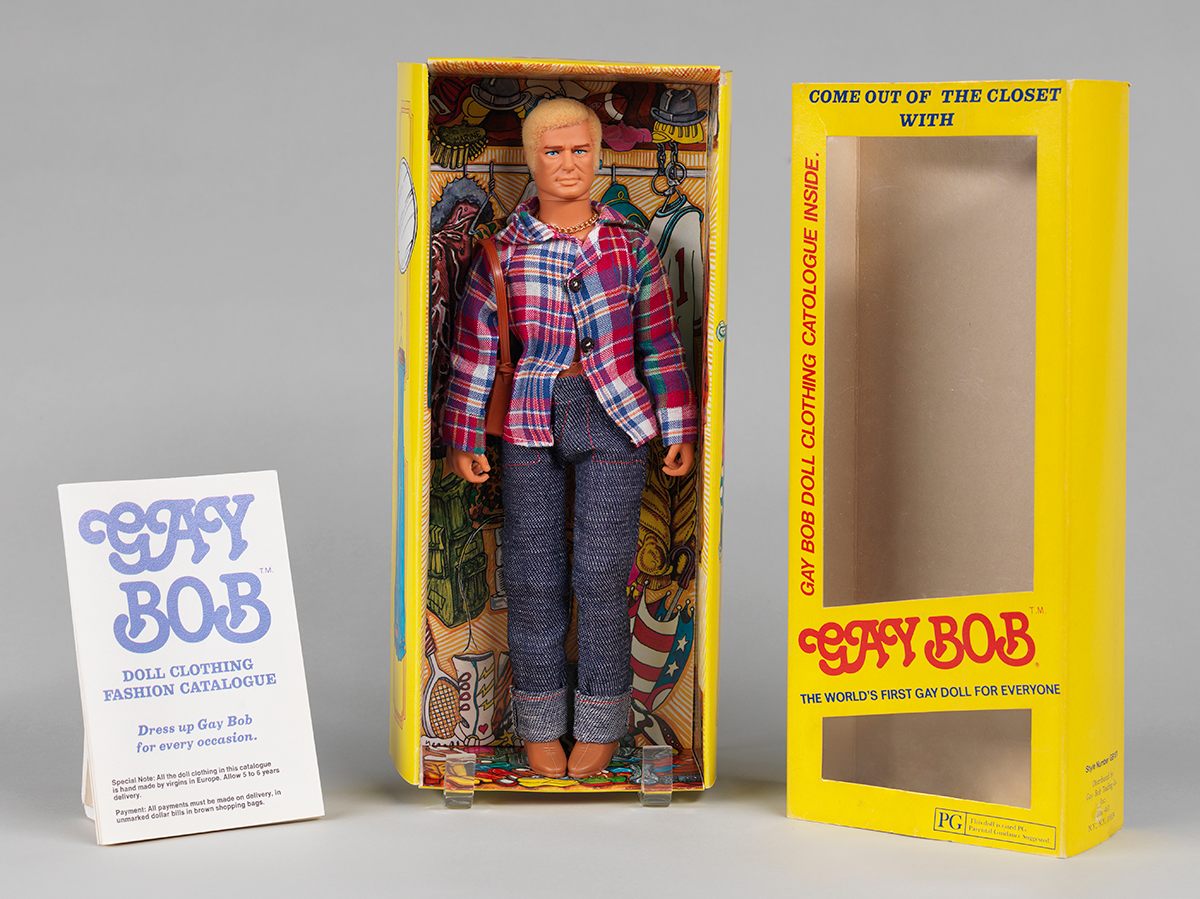

Gay Bob, who was meant to resemble a cross between Robert Redford and Paul Newman, was blond, with a flannel shirt, tight jeans, and one pierced ear. The doll gave anti-gay organizations plenty to fear; intrinsic within it was a celebration of gay identity, evidenced by Gay Bob’s programmed speech. “Gay people,” Bob said, “are no different than straight people… if everyone came ‘out of their closets’ there wouldn’t be so many angry, frustrated, frightened people.”

In a cheeky move, the box in which Gay Bob was packaged came in the outline of a closet, so that when he left his box, he was literally coming out of the closet. Gay Bob explained: “It’s not easy to be honest about what you are — in fact it takes a great deal of courage… But remember if Gay Bob has the courage to come out his closet, so can you.”

The affirming message was no accident. The doll’s creator, Harvey Rosenberg, a former advertising executive who developed marketing campaigns for various corporations, wanted Gay Bob to “liberate” men from “traditional sexual roles.” He created the doll soon after a series of shocks rocked his life: in quick succession, his marriage fell apart and his mother became seriously ill. He decided that his next projects would need to be of great personal significance.

Though Gay Bob was certainly humorous—the doll was designed to be anatomically correct, and prominent gay activists such as Bruce Voeller told reporters that people should “deal with [the doll] lightly and enjoy it”—Rosenberg’s intentions seem to have been sincere. When asked why he would pour $10,000 of his money into the Gay Bob’s production, he replied, “we had something to learn from the gay movement, just like we did from the black civil rights movement and the women’s movement, and that is having the courage to stand up and say ‘I have a right to be what I am.’”

When Gay Bob hit stores in 1978, that right to be gay and equal was once again under attack, most notably from Anita Bryant, a singer and well-known brand ambassador who mobilized opposition to a Dade County, Florida ordinance that outlawed discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Fixating on its impact on public schools, Bryant claimed that the existence of LGBT school teachers would threaten the well-being of local students. “Homosexuals will recruit our children,” she warned. “They will use money, drugs, alcohol, any means to get what they want.” In June 1977, she had the rule repealed, and her anti-gay crusade—which gained widespread media attention—sparked similar ventures in Minnesota, Oregon, Kansas, and California.

Gay Bob, which sold 2,000 copies in its first two months, appeared in the heat of these political battles. It was no real flashpoint of its own, but it served as a humorous trophy—and a sign of changing times—for those fighting against Bryant.

Initially sold through mail-order ads in gay-themed magazines, Gay Bob soon expanded into boutique stores in New York and San Francisco. Rosenberg even pitched it to major department store chains, one of which liked the idea (but ultimately did not purchase it). And, it turns out, those consumers who feared the introduction of more “disgusting” dolls were partially correct—Rosenberg soon gave Gay Bob a family of his own, with brothers Marty Macho, Executive Eddie, Anxious Al, and Straight Steve (who lived in the suburbs and wore blue suits), and sisters Fashionable Fran, Liberated Libby, and Nervous Nelly.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook